Paper: Dureuil, M., Boerder, K., Burnett, K. A., Froese, R., & Worm, B. (2018). Elevated trawling inside protected areas undermines conservation outcomes in global fishing hot spots. Science, 362, 1403–1407. DOI: 10.1126/science.aau0561

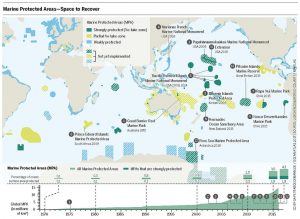

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) aim to protect ocean ecosystems by preserving biodiversity. These protected areas come in many shapes and sizes and can have a variety of management plans: some prohibit all destructive activities while others may allow different recreational activities like fishing or boating. The goal is that by setting aside these protected spots in the ocean, we give the ecosystem a break from destructive activities (i.e. overfishing, drilling, and mining) and, thereby, allow the ocean some respite in which to recover. MPAs have been shown to increase biodiversity and restore the ecosystem within the area and even increase the amount of fish outside of protected areas due to “spillover effects”. By increasing biodiversity, it is also hoped that ecosystem will be more resilient in the face of damages we cannot as easily shield against, like climate change.

In theory, MPAs are a fantastic solution to ocean conservation issues, however, in practice there have been some issues – many stemming from the fact that it is difficult to patrol and enforce management on large swaths of the ocean. If you are out boating or just looking at google earth, it is unlikely you will see a fenced in area with a large “No Fishing: Marine Protected Area” sign. In fact, even on land where we have some of those barriers, many protected areas still experience anthropogenic (human-induced) pressures. To see if marine protected areas similarly experienced destructive activities detrimental to conservation goals, a group of researchers investigated the efficacy of MPAs in European waters.

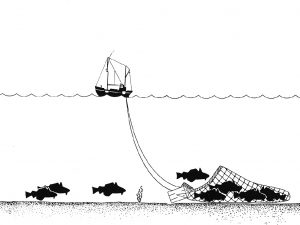

Europe is a hotspot for fishing activity and has an impressive network of protected areas, with approximately 29% of territorial waters falling in protected jurisdictions. While all of these MPAs have different regulations and management practices in place, they have all been designated to preserve areas from harmful human activities, like overfishing. Trawling, a common industrial fishing practice that targets bottom-dwelling species, is particularly damaging because the nets that are dragged along the seafloor harm fragile ecosystems and tend to capture many unwanted, often endangered, fish species.

Researchers examined how frequently fishermen were trawling in MPAs and outside of their boundaries by tracking the fishing vessel location and movement patterns (read how scientists with Global Fishing Watch track fishing practices and determine economic impacts of fishing). The team examined fishing practices within and surrounding 727 MPAs and found that even though MPAs should be protecting from this horribly destructive practice, commercial trawling took place in 59% of the European MPAs. Worse yet, trawling activities are actually elevated within MPA boundaries! In 2017, trawling activities were 38% higher within MPAs than outside of them.

To try and quantify the impact of trawling in these areas, researchers looked at the biodiversity within and surrounding the MPAs. Sharks, skates, and stingrays (collectively referred to as elasmobranchs) are particularly susceptible to trawling, often caught by gear even when they are not directly targeted by fisherman. Because of this, scientists can use elasmobranchs as an indicator of how other groups of fishes are faring in the area. Furthermore, scientists are concerned about declining elasmobranch populations because they are important to regulating ecosystem health and many species are already threatened or endangered.

The scientists assessed the elasmobranch populations both inside and outside of MPAs over a 9 year period (1997 – 2016) to see how abundance changed over time and in the presence of trawling activities. Mirroring the data on trawling activity, elasmobranchs were caught 2 to 3 times more frequently outside of MPAs than within them. These data are rather unexpected as MPAs are specifically put in place to increase population sizes and have been shown to increase shark populations in other areas. The researchers examined if elasmobranch populations corresponded with different MPA factors (such as MPA size and age, both factors which are thought to impact fish population sizes) and habitat types but found that the only factor capable of explaining elasmobranch abundance was fishing. The more trawling in an area, the lower the elasmobranch abundance. However, when there was less trawling, elasmobranch abundances were higher and continued to increase over time, a sign of populations recovering from overfishing.

Based on the elasmobranch abundance, it is likely that other species and the ecosystems on a whole have similar responses to trawling activity: increase trawling and decrease ecosystem health; decrease trawling for a long period of time and the ecosystem may recover. MPAs are set up to protect against these destructive habitats and encourage ecosystem recovery. It is important to note that MPAs are not trying to reduce fishing just to keep more fish in the sea. The goal is that by helping patches of the ocean recover, the ocean will be less susceptible to anthropogenic disturbances. One problem, say overfishing, may not be enough to wreck an ecosystem. But when we continue to compile more and more issues – throw pollution, drilling, and climate change on top of overfishing – the ecosystem may be too weak to recover. It is very similar to your own health. Miss some sleep and you may start dragging, but you will survive. Miss some sleep AND you’re stressed about your impending finals AND then you get the flu – it is going to take you longer to recover. In a sense, by setting up MPAs we are trying to boost the ecosystem’s immune system.

Unfortunately, this research proves that even the best intentions can go awry. It is simply not enough to declare a part of the ocean as a protected area. We must actively work to enforce and manage the MPAs if we have any hope that conservation goals will be met.

I received my Master’s degree from the University of Rhode Island where I studied the sensory biology of deep-sea fishes. I am fascinated by the amazing animals living in our oceans and love exploring their habitats in any way I can, whether it is by SCUBA diving in coral reefs or using a Remotely Operated Vehicle to see the deepest parts of our oceans.