Journal source: Hale et al. 2018, Six decades of change in pollution and benthic invertebrate biodiversity in a southern New England estuary, Marine Pollution Bulletin 133: 77-87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.05.019.

The surface waters often obscure our view of the bottom, or benthic, habitats, but while out of sight, these systems can serve as a time capsule of human stressors that have caused reductions in biodiversity and altered species composition. Biodiversity, the number of different types of organisms living in an ecosystem, is the cornerstone of ecosystem functioning and the services they provide to people. Benthic (bottom habitat) biodiversity directly benefits humans because the different invertebrates living there. For instance, mussels help filter water which aids in water quality, while various shrimps, snails, and crabs form an important component of the diets of commercially harvested seafood.

Marine benthic communities around the world have experienced biodiversity loss because of many different human activities, such as dredging, overfishing, pollution inputs, and watershed development. Estuaries, where freshwater inflows from surrounding lands meet the ocean, receive upstream pollution discharges and runoff from impervious surfaces and agriculture. Estuaries share linkages with the land and sea, and their benthic communities can be used to monitor changes in biodiversity and link observed changes with human activities.

In the presented study, Hale and colleagues from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory explored six decades of change in the benthic invertebrate communities of Narragansett Bay. The researchers also sought to link changes in benthic invertebrate biodiversity to anthropogenic impacts, such as eutrophication and sediment contamination.

Narragansett Bay is a northeastern U.S. estuary in Rhode Island and Massachusetts. The bay’s benthic communities support ecosystem functions and services such as shellfish production and shoreline protection. The bay is surrounded by a large watershed with over 1.9 million people, a high degree of urbanization, and waste water treatment facilities (WWTF) that discharge effluent into streams that flow into the estuary.

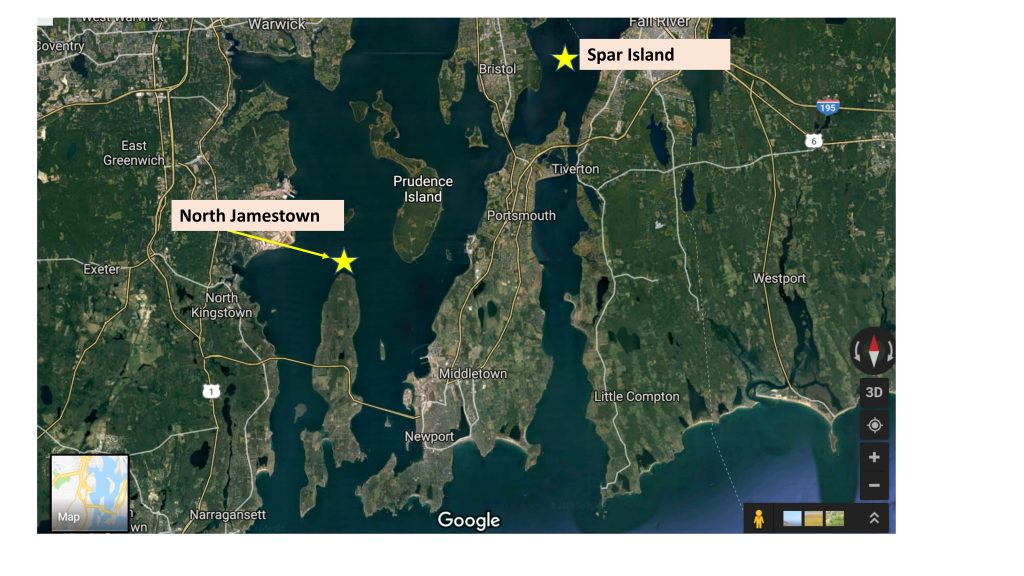

To analyze changes in the bay, the researchers used benthic monitoring data from the EPA’s national coastal assessment programs and other long-term studies on Narragansett Bay. These programs used standardized protocols for sample collection and analysis, collected concurrent physical and chemical data from the water column and the sediments. The sample collection made it possible for the authors to compare biodiversity across several decades. Included in this dataset was one reference site in Narragansett Bay called North Jamestown that is minimally influenced by land use and WWTW discharge. Reference (or control) sites are important to use as a stable comparison for other sites that may be more susceptible to human impacts. To complement the reference site, the authors chose one impacted site called Spar Island in Mt Hope Bay. This site has experienced a number of human changes from watershed development and combined sewer overflows (CSOs). For each year of available data, the authors calculated benthic invertebrate diversity and related long-term trends in biodiversity to water column measurements, such as nitrogen concentrations, which can indicate pollution inputs.

What did they find?

After compiling 60 years of data from previous studies and examining biodiversity trends with relevant water quality measurements, the authors found significant changes had occurred in the benthic invertebrate communities of Narragansett Bay. While community composition changed, the authors noted that biodiversity throughout the bay did not respond drastically to human stressors, except for Spar Island, which showed a distinct drop in biodiversity from the 1970s to the 2000s. The authors also found that changes in community composition were linked to patterns of eutrophication, hypoxia (oxygen depletion), and sediment contaminants, such as petroleum products and heavy metals. By comparing community composition across decades, the authors could look at species that dominated the bay. The authors found that the species that dominated and contributed to decadal changes in community composition had small body sizes and short life cycles, such as the polychaete Mediomastus ambiseta. These life history characteristics allow these species to respond more rapidly to fluctuating habitat conditions; for example, small amphipods can colonize patches of good quality benthic habitat if other areas are too low in dissolved oxygen.

While biodiversity may not have declined with increasing human stressors, as originally expected, it began to show a weak upward trend beginning in 2005, which the authors attribute to the 50% reduction in total nitrogen inputs from WWTFs that empty their effluent into the bay. However, several more years of benthic monitoring in the bay will be necessary to determine if this upward trend continues as more efforts are made to reduce nutrient inputs to the estuary.

The bigger picture

This study was able to use long-term benthic monitoring data to determine if changes in biodiversity could be related to historical and present human influences on Narragansett Bay. This study, among others, sheds light on the value of historical data for identifying ecological patterns and linking them with anthropogenic stressors. While benthic monitoring is important, there is a need for multiple research groups to use standard sampling methods so that more studies can apply Hale and colleagues’ approach to other marine ecosystems. Biodiversity, an important feature of marine ecosystems, is also a useful tool for humans to help guide management and restoration efforts in complex habitats.

Kate received her Ph.D. in Aquatic Ecology from the University of Notre Dame and she holds a Masters in Environmental Science & Biology from SUNY Brockport. She currently teaches at a small college in Indiana and is starting out her neophyte research career in aquatic community monitoring. Outside of lab and fieldwork, she enjoys running and kickboxing.

An interesting and very important study, and well presented in your synopsis. Your concluding “The bigger picture” summary is especially on-target about using comparable methodologies, and should be required reading for researchers. A very concisely written article – well done.