Journal source: Ojaveer, H., B. S. Galil, J. T. Carlton, H. Alleway, and others. 2018. Historical baselines in marine bioinvasions: implications for policy and management. PLoS ONE 13:e0202383.

Marine ecosystems all over the world face threats from climate change, pollution, and physical destruction of marine habitats. Recently non-indigenous species (NIS) have also been identified as a serious threat that may alter marine habitat structure and function. NIS is another acronym for invasive species, which can be animals and plants that are native to one geographic region, and ended up in another place. Usually, humans are responsible for allowing species to become established in a new area. From globe-trotting ships that carry hitchhiking zebra mussel larvae, to local recreational boating, there are multiple routes by which species can invade a new habitat. Because of these multiple pathways, nearly all marine habitats are impacted in some way by NIS.

Often, NIS have caused many negative ecological consequences, such as lowered species diversity, reduction in productivity of the habitat, and sometimes, loss of ecosystem function. The presence of NIS can even impact human health- if you’ve ever walked along a beach riddled with invasive zebra mussel shells, you may have learned the hard way that invasive species can be painful to humans!

A specialized branch of marine and aquatic science, invasion ecology has sought to understand the causes and consequences of marine invasions by NIS. In order to understand NIS, we really need to look at the history of marine invasions. In a recent paper, Ojaveer and colleagues discuss this history as well as the challenges in preventing future invasions.

A lesser-known history of pre-industrial era invasions:

Invasive species might be introduced by seemingly harmless activities such as hiking, where organisms or their seeds can attach to clothing and disperse to other habitats. Early maritime shipping played a fundamental role in transporting people and goods, but it also allowed for the spread of invasive species.

Shipping expanded in the late 1500s, but we have little insight into marine invasions of this era. Some researchers today have performed experimental studies on replicas of 16th century ships to provide insights on what species may have been transported by ships in the 1500s. Researchers noted that as ships visited various ports, they potentially carried organisms from one port to the next. As the ballasts (bottom portion of ships) were filled with water in one location to help weigh down the ship, the ship could also harbor unintended hitchhikers such as larval mussels or fish, which would then be released into a new area once the ballast water was later expelled.

Records of ballast-caused introductions began to appear in the 1700s and early 1800s. One of the common North American salt marsh plants, Spartina alterniflora, was collected in France in 1803 and later reported in South America in 1817, likely introduced via ship ballast. As an ecosystem engineer, this plant caused major changes to the west coast mudflat habitats of South America. Researchers also hypothesize that ship ballast allowed for the spread of the European periwinkle snail to North America, where it is a common member of intertidal zones along the eastern Atlantic coast.

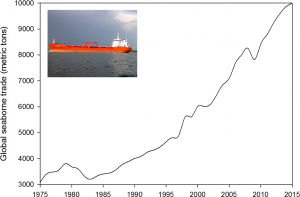

The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed key innovations to ship design and manufacturing. Markets became more globalized, and shipping increased to support world trade. Shipping routes changed from direct port-to-port services along major East-West routes to a “hub and spoke” network that has increased connectivity among ports and harbors. Along with these expanding shipping networks, manmade canals added another dimension to connect markets and offered NIS ever more opportunities for dispersal. As ship size, speed, and number increased to accommodate world trade, the number of organisms potentially transported on ships also increased. For example, researchers estimate that ballast water from a single ship entering the North American Great Lakes could contain anywhere from 10,000 to 8 billion live individuals of various species! The zebra mussel entered the Great Lakes via ship ballast water in the 1980s. Since its invasion, this species has ruined critical infrastructure such as municipal pipes, costing the US economy $1 billion annually. Indeed, the zebra mussel is likely the most economically and biologically destructive NIS in North America.

Modern-day monitoring of NIS

Considering the centuries-old legacy of marine invasions, it is very important for scientists to keep track of current invasions and keep tabs on organisms that have potential to invade and displace native species. Major research on marine invasions emerged initially in the 1960s, and records on NIS present in different geographic regions are very patchy.

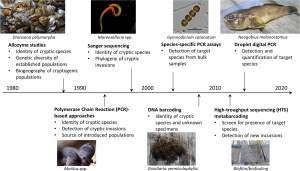

Currently, research groups collecting NIS data in different regions do not use a global standard sampling methodology, which makes it challenging to untangle invasion patterns and effects of invasions on communities over time. Despite these challenges, citizen science campaigns, in which members of the public help scientists detect NIS by sharing photos and locations on web-based applications such as “Imapinvasives”, play a key role in NIS detection and surveillance. Additionally, DNA-based protocols can detect even the tiniest hint of a NIS from a water sample, which is especially valuable during the early stages of invasions and may help researchers stop a potential invasion.

Societal and policy aspects

Why do we bother to consider the historical aspect of marine NIS? Well, human perceptions and government actions toward managing NIS have changed over time. Introduction of marine NIS was not considered a potential threat until the early 1980s, when the zebra mussel entered the North American Great Lakes. Although invasion scientists provide evidence of ecological and economic impacts of marine NIS, public awareness and perceptions of NIS can determine the level of support for policy and management actions used to control potentially harmful NIS. Partly due to the patchy reports on marine NIS, the impacts of many NIS are unknown, which can lead the public to not consider NIS a serious threat. Often, it is not until the public witnesses very apparent and destructive consequences of NIS, steps taken to remedy the situation become reactive, rather than proactive.

The future is now

By looking to the past for clues about patterns of invasive species in marine ecosystems, scientists can work to improve monitoring programs and encourage the public to be concerned about NIS. As our world becomes increasingly connected, potential NIS have multiple ports of entry into new marine habitat, making it ever more critical that we support local efforts to reduce the risk of marine invasions. Maybe now, you are inspired to participate in local efforts or web platforms such as Imapinvasives, to help organizations and research groups monitor and stop the spread of NIS!

Kate received her Ph.D. in Aquatic Ecology from the University of Notre Dame and she holds a Masters in Environmental Science & Biology from SUNY Brockport. She currently teaches at a small college in Indiana and is starting out her neophyte research career in aquatic community monitoring. Outside of lab and fieldwork, she enjoys running and kickboxing.