Brunner I, Fischer M, Ru ̈thi J, Stierli B, Frey B (2018) Ability of fungi isolated from plastic debris floating in the shoreline of a lake to degrade plastics. PLoS ONE 13(8): e0202047.

About a year ago, I decided to make a move towards reducing my plastic consumption. Working in environmental conservation leaves you with a crushing grey cloud of guilt any time you fall into bad habits : forgetting your reusable bags, buying food wrapped in plastic, wearing yoga pants, buying a disposable Starbucks cup, and many other privileged wasteful behaviours.

So I made a commitment to cut certain plastic-containing products and activities out of my life, intending to do my duty to environmental sustainability and to encourage my family and others to do the same. So far, it’s going well. It’s been difficult to find a butcher and dairy that will allow us to purchase plastic-free meats and milk products, but the rest of our food now comes without packaging. I don’t let myself go to the store without bags, even if it’s inconvenient to stop at home first, and I’m slowly switching to reusable feminine products. I am having a hard time with my clothing, though.

The majority of our clothes are now made from synthetic plastic polymer fabrics that give them a stretchy character – the nylons, organzas, faux leathers and furs. Your shirts, your shoes, and my treasured yoga pants all contain at least some plastic threads, some upwards of 75%. It’s become so ubiquitous that it’s difficult to find fabrics that don’t contain any plastic (look for labels like “100% cotton” and ”100% linen”).

This might explain why plastic microfibers are being found so often in our oceans.

Plastic pollution comes in all shapes and sizes. From large floating whole-piece plastics like bags, pens, and bottles all the way to tiny microplastic particles, the product of either early-production losses or the byproduct of slow breakdown of larger pieces. The trouble with plastic is that, unlike other forms of pollution, it never really breaks down into its constituent forms. Instead, plastic photodegrades (breaks apart in response to light) into smaller and smaller pieces, chemically identical to the original larger piece. Every time you wash your clothes, plastic microfibers enter our waterways destined for the ocean. There, they get taken up by the marine food web and enter the sediment, adsorbing harmful chemicals and choking out ocean life.

Luckily for my yoga pant addiction, Swiss researchers recently discovered a number of fungi that seem capable of decomposing polyurethane, the kind of plastic often used in clothing and responsible for microfiber pollution.

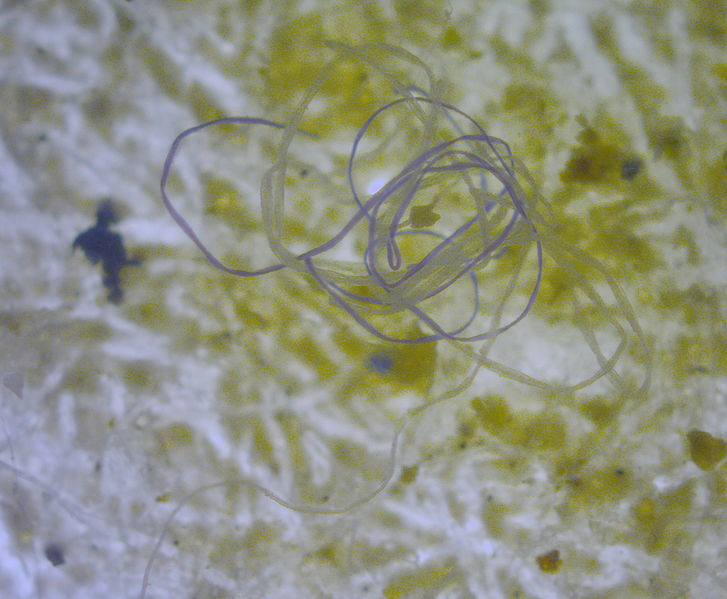

Brunner et. al. from the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow, and Landscape Research published an article in PlosONE recently that show how certain fungi can decompose plastic. Taking samples from Lake Zurich in Switzerland, the researchers presented separated plastic debris particles in petri dishes with a growing medium rich in nutrients important for fungal growth. After a few weeks, they found hundreds of different fungal strains growing in the plates and were able to isolate and identify 13 species (12 Ascomycota and 1 Oomyctoa, in case you’re interested!)

They then tested the ability of the fungi to degrade plastics by isolating fungal inoculi (basically fungal patches) and placing them on one of three surfaces: polyurethane (the plastic in synthetic fabrics), polyethylene (the plastic in bags, toys, pens and other common products), and lignin (a plastic-like but plant-derived polymer that is also difficult to break down).

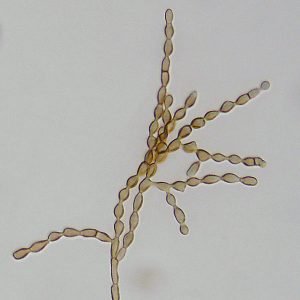

Four species found on the plastic debris were able to break down the polyurethane, with Cladosporium cladosporioides being the most efficient. Surprisingly, very few of the fungi that naturally degrade lignin, which is the natural tough material plant cell walls are made of, were able to also degrade the plastic. No fungi were able to degrade the polyethylene, the polymer that at least of third of plastics are derived from. The researchers also tested 23 other fungi species not found on the plastic debris from Lake Zurich, and only found 3 more fungi capable of degrading polyurethane.

So it seems rare to find a fungus that can degrade the plastic particle it’s hitched a ride on. However, Brunner et. al.’s results make me feel a little better about not being able to kick my yoga pant habit. Polyurethane seems a little easier to decompose, meaning given the right fungal environment, those pesky microfibers might adequately break down after leaving your washing machine. But polyethylene is tough, and even polyurethane plastics seem unlikely to degrade in nature by fungal action alone. However, if researchers like the Swiss group can identify microorganisms that do degrade different polymers, it might allow plastic manufacturers to design new plastics with those natural degrading agents in mind.

For help cutting your plastic habit, check out these tips from the awesome blog “My Plastic Free Life”

Hi! I’m Rebecca Parker. I’m an ecologist and plant lover working in non-profit conservation in Nova Scotia Canada. I trained at Dalhousie and Ryerson University, where I completed a Masters in Environmental Science and Management. I like botany, wetlands, and wetland botany! On the sciencey side, I like to write about current topics in population and community ecology, but I’m also really interested in environmental outreach, how exposure to science and demographics affect environmental values and behaviours, and best practices for building community capacity in environmental stewardship. Check out my instagram for photos of the awesome nature I see through my work.