This article is part of a collaboration between Sharkbites Saturday and the Shark Research & Conservation Program (SRC) at the University of Miami.  This contribution comes from Chelsea Black, a master of professional science candidate in marine conservation focusing on shark immunology.

This contribution comes from Chelsea Black, a master of professional science candidate in marine conservation focusing on shark immunology.

Article: Speed, C. W., Cappo, M., & Meekan, M. G. (2018). Evidence for rapid recovery of shark populations within a coral reef marine protected area. Biological Conservation, 220, 308-319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.01.010

Introduction

The life history traits of sharks leave them highly susceptible to exploitation and depletion rates that far exceed their natural recovery potential, forcing many species to race against the clock of extinction. Sharks are slow to reach sexual maturity, have long gestation periods, and reduced fertility. Together, all of these factors result in many populations becoming depleted without an ability to bounce back after fishing pressures.

Why should we care?

Declining shark populations is of particular concern due to the abundance of emerging evidence that supports their important role in the ocean ecosystem. There is evidence that the absence of apex predators, such as sharks, may affect the ability of coral reefs to recover from disturbances, as well as promotes the outbreak of crown-of-thorns starfish which have detrimental impacts on reefs (Speed et al. 2018). In addition, there is evidence that certain shark species are a valuable tourism resource that provide significant benefits to coastal and island economies (Hammerschlag et al. 2018).

What’s the problem?

Unfortunately, there is a lack of understanding of the rate at which populations of reef sharks may recover from over-exploitation. This leaves a gap for management strategies, as there are no “baseline” measurements to compare shark abundance. It would be extremely hard to determine that shark populations are on a rise in a specific location, if there is no baseline information on what the populations previously were. To say with certainty that a population of any species has “fully recovered” it must be comparable to something, and there must be an end goal.

The study

A study published this year by Speed et al. (2018) provides some of the first data on the recovery rate of reef shark populations within a coral reef ecosystem. Coral reef systems in Western Australia provide an area of natural experiment to examine the recovery of Carcharhinus ambylrhynchos, the gray reef shark (Figure 1), from over-fishing and the role of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) in the aid of their recovery. Prior to 1988, Ashmore Reef (Figure 2) was subjected to both targeted commercial shark fishing as well as legal and illegal subsistence fishing by Indonesian fishermen (Speed et al., 2018). A no-take MPA was then established but only enforced through occasional monitoring between 2004 and then monitored by a government vessel beginning in 2008.

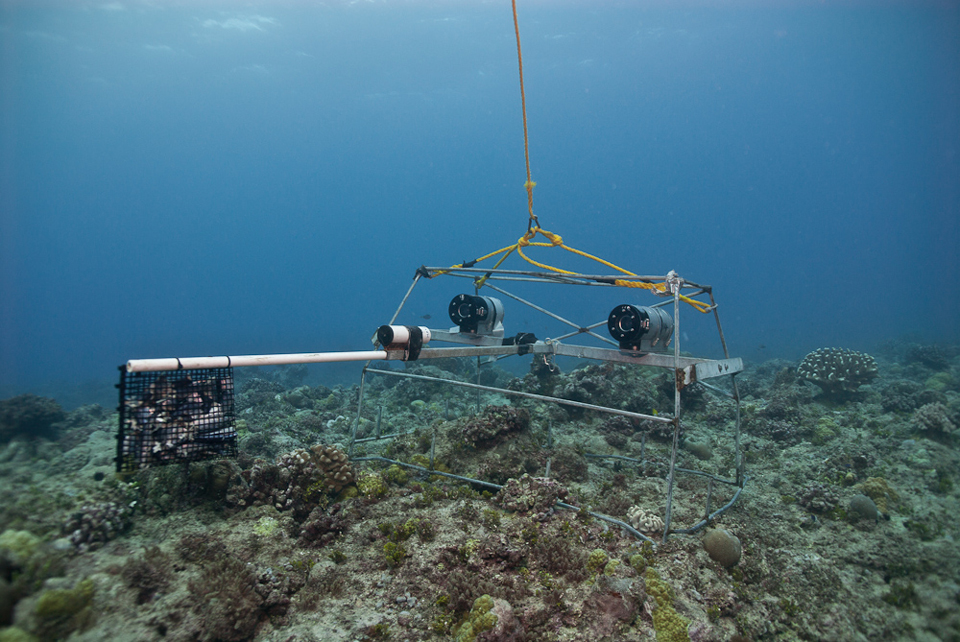

The use of Baited Remove Underwater Videos (BRUVs) (Figure 3) in 2004 was used to determine reef shark abundance, and then again in 2016 at the Ashmore Reef location. The abundance of reef sharks was 4.6 times greater in the year 2016.

Near Ashmore Reef is Rowley Shoals, a reef system that has well managed MPAs and little fishing pressure over the past three decades (Speed et al. 2018). Rowley Shoals provides a healthy shark population for comparison. After 12 years of protection at Ashmore Reef, reef shark assemblages are similar to those at Rowley Shoals, suggesting that the Ashmore Reef shark population has successfully recovered from over-fishing and exploitation effects.

In an original model, it was predicted that reef shark populations at Ashmore Reef would not fully recover until the year 2024 at the earliest, and as late as 2084. By comparing the 2016 abundance at Ashmore Reef to that of Rowley Shoals, it is evident that shark populations have recovered exponentially faster than expected.

What does this mean?

The results of this study suggest that the establishment of a no-take MPA can aid in the recovery of certain shark communities at all trophic levels with adequate enforcement, and at rates far greater than previously expected. These results are encouraging for the sake of our healthy oceans, and also remind us that both the benefit of protected marine areas, and the recovery potential across shark species should be individually examined to determine success. The fact that the abundance of shark populations increased exponentially after the MPA was properly enforced shows that the establishment of a protected area is essentially a “paper tiger” that sounds threatening but in reality, is ineffectual without proper enforcement. With proper enforcement, even small MPAs have the chance to help many shark populations rebound from heavy exploitation.

Additional references

Hammerschlag, N., Barley, S. C., Irschick, D. J., Meeuwig, J. J., Nelson, E. R., & Meekan, M. G. (2018). Predator declines and morphological changes in prey: evidence from coral reefs depleted of sharks. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 586, 127-139.

I am currently a PhD student studying marine science at the University of Massachusetts Boston, with my research based at the New England Aquarium. My research interests center around conservation physiology of fishes, particularly sharks, in relation to climate change. I have a passion for scientific outreach and communication with my biggest triumph being my participation in an hour long science-based episode of Shark Week 2016 entitled Tiger Beach. In my spare time I like getting outside hiking, rock climbing, diving, and practicing my yoga headstands.