Unlike fictional cyborgs, this unlikely robot is powered by a biological process millions of years old.

Reference: Phillips, N., Draper, T.C., Mayne, R., Adamatzky, A. (2022). Marimo actuated rover systems. J Biol Eng 16(3). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13036-021-0027

The cyborg — part biological, part mechanical being — is found throughout popular culture. From Darth Vader to Iron Man, the possibilities presented by the intricate combination of physiology and technology have thoroughly captured our imagination. But real biological robots could look quite different from flashy fictional superhumans. Researchers at the University of West England’s Unconventional Computing Laboratory created a biological robot with much more humble beginnings: a little ball of algae.

Life in MARS

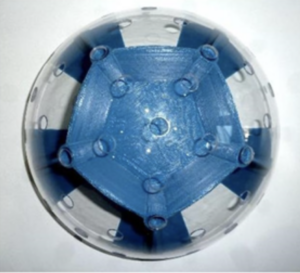

Marimo are filamentous algae found mostly at the bottom of lakes and rivers, rolled into ball-like shapes by gentle wave action. Their characteristic round, fluffy appearance led 19th century Japanese botanist Takiya Kawakami to name them “mari-mo”, a combination of the words for “bouncy ball” and “a plant that grows in water”. Researchers placed this charismatic algae into its own 3D printed exoskeleton with small openings placed around it, not unlike a whiffle ball. The researchers called the robo-marimos MARS, or Marimo Actuated Rover Systems.

Doing the Mari-most

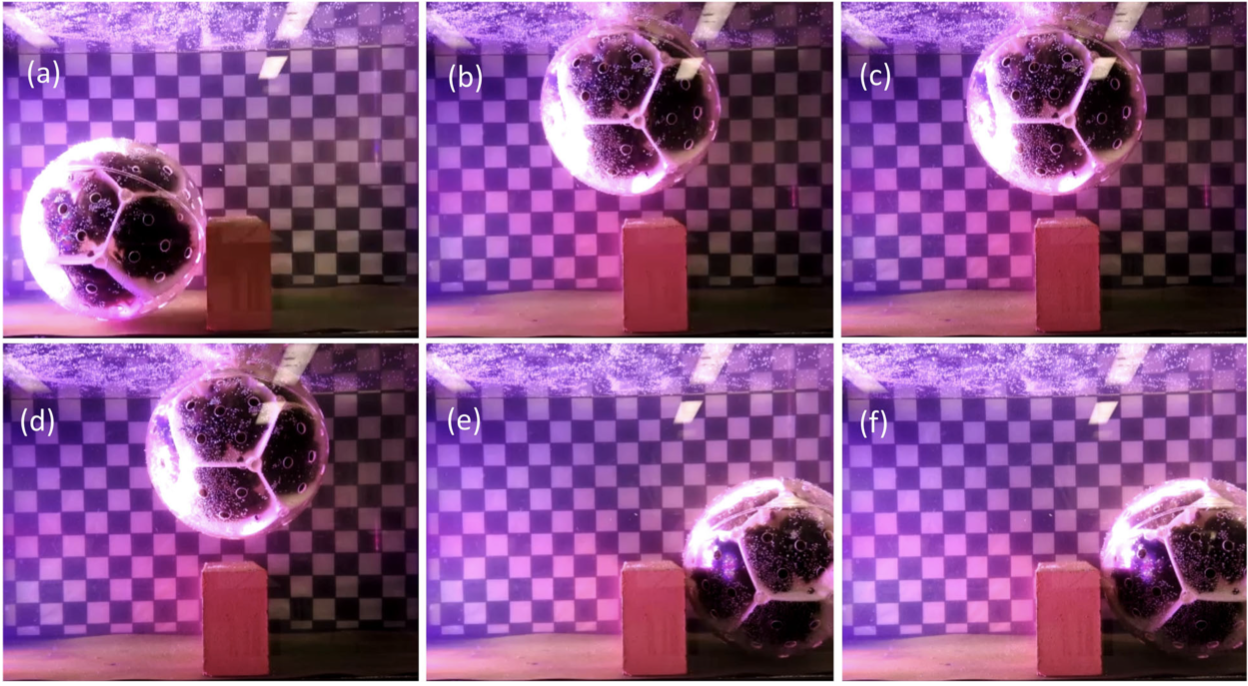

Unlike many of its fictional counterparts, MARS does not give marimo superhuman abilities. Rather, it works with marimo’s basic biological functions to move. Like most plants, marimo photosynthesize, capturing sunlight and releasing oxygen. While oxygen is normally released into the surrounding water, MARS traps the oxygen bubbles in a cage. As the bubbles build up, they create enough force to make MARS rotate, propelling it forward. As it rotates, the openings in the exoskeleton act as vents for oxygen to escape, allowing the process to repeat.

MARS can even bypass obstacles— if obstructed, the accumulated oxygen makes it buoyant, allowing it to float over the obstruction. When no longer blocked, MARS can continue rotating and sinks back down to the ground. MARS transforms photosynthesis into a means of locomotion, allowing the system to traverse its environment independently.

Slow, silent and steady

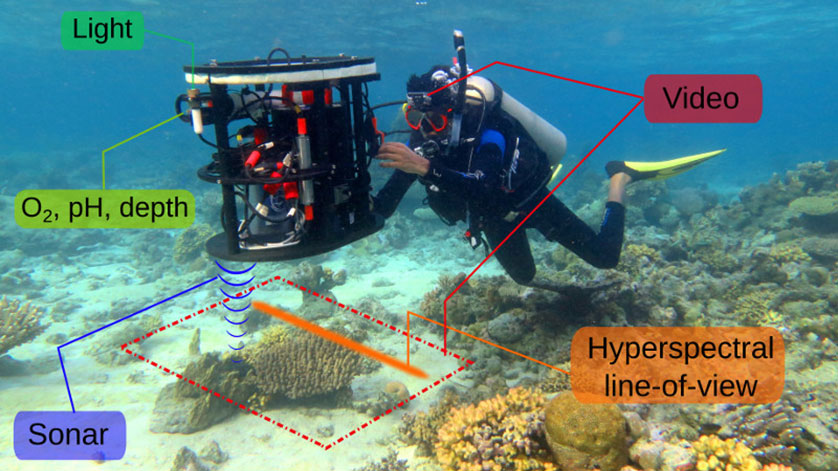

In comparison to conventional rovers, MARS might be beneficial to deploy when device longevity is key. Marimo have long lifespans (the oldest recorded is over 200 years old), and the MARS exoskeleton has few moving parts and is entirely solar powered. As such, the researchers are hopeful that MARS will be able to function autonomously for long periods of time without being constrained by battery life or maintenance issues. Outfitting MARS with sensors could allow it to gather real time data over longer periods of time, such as water quality and pollution monitoring in aquatic ecosystems.

MARS’ unique biological nature also means it does not emit electromagnetic signals, which could be advantageous in specialized scenarios. Operations such as detecting underwater mines rely on sensitive equipment — MARS’s electromagnetic silence means it won’t interfere with instrument readings.

Conclusion

MARS has been compared to Iron Man’s suit, but its understated appreciation of biology is in stark contrast to the flashy heroics associated with robotics in popular culture. MARS may not be able to fly or shoot lasers, but it represents the ways in which we could embrace biology itself as technological innovation. Sometimes scientific advancement doesn’t announce itself like a billionaire encased in a weaponized suit. It might look like a little ball of algae on a sunny day, leisurely rolling along the bottom of a lake.

I’m a Ph.D. candidate in Biology at Caltech. I study animal regeneration across phylogeny— my interests include the evolution and development of weird animals and obscure science history.