Knipp, A.L., Pettijohn, J.C., Jadot, C. et al. Contrasting color loss and restoration in survivors of the 2014–2017 coral bleaching event in the Turks and Caicos Islands. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 331 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-2132-6

Introduction

Coral reefs are hot spots for life in the oceans. They create habitats and provide resources for animals such as fish, crustaceans, and mollusks. Although reefs only account for 1% of the ocean floor, they support 25% of the all the species that live in the ocean. Something that may surprise you about corals are that they are made up of two different species that live together in what is called a mutual symbiotic relationship. Mutual symbiotic relationships occur when two species benefit from each other’s presence in some way. This symbiotic relationship is made up of the coral polyps, which have a hard exterior and are related to anemones, and small photosynthetic organisms called zooxanthellae which live inside the coral. The coral protects the zooxanthellae with its hard exterior, and zooxanthellae provide oxygen and nutrients that help the coral survive.

When water temperatures get too warm this relationship becomes stressed, and their symbiosis breaks down. The corals become pale and colorless as they start to die because they are no longer getting their essential nutrients from zooxanthellae.

During this process, the expelling of the zooxanthellae by coral is referred to as coral bleaching, and while some corals can reestablish their symbiosis with zooxanthellae and recover their health, others might not be so lucky.

In 2015 there was a naturally occurring event called El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) that significantly raised sea surface temperatures in certain parts of the world. These temperatures decreased to relatively normal ranges at the end of 2017, but not before damaging the corals around the Turks and Caicos Islands. Knipp and co-authors aimed to find out just how these reefs were impacted by ENSO by looked at coral bleaching during the 2014-2017 Global Bleaching Event (GBE).

What did they do?

Knipp and co-authors used citizen scientists to measure coral color and gather the data they needed for this study. Citizen scientists are members of the general public who collaborate with a professional scientist or institution to conduct a scientific study or experiment. There are many ways to participate in citizen science, from downloading the app iNaturalist and snapping pictures of things that live in your backyard to volunteering at a local institution.

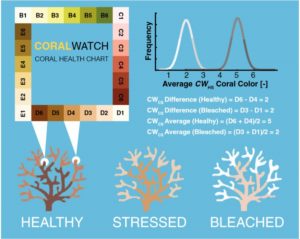

In this case, the citizen scientists were students at the School for Fields Studies located in Turks and Caicos. These students surveyed the coral reefs around the island by determining the color of corals using the CoralWatch Coral Health Chart. Healthy corals were darker in color because they still had their living tissue and zooxanthellae, and lighter colored corals were either “stressed” or “bleached’ depending on how much tissue they had lost.

Students also collected data on water temperature, time of day, depth of the survey, and the species of coral. There were 104 of these surveys completed from 2012 until 2018, which gave the scientists the perfect time frame to look at the health of the corals before the bleaching event, during the bleaching event, and after the bleaching event.

What did they find?

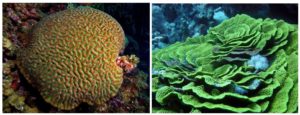

Two major types of coral were covered in this study: boulder-type corals, and plate-type corals; think big and round or thin like flower petals. These scientists found that both types of corals flourished before the bleaching event, but plate-type corals took a harder hit when the water temperature increased. However, both types of corals rebounded as the waters cooled off near these islands. Plate-type corals returned back to their normal color as the zooxanthellae reentered their homes, and the boulder-type corals also recovered as the ocean’s temperature began to cool.

The researchers did want to make a note that the islands of Turks and Caicos are in the northern part of the Caribbean Sea, so the water temperatures did not get quite as warm as in other surrounding areas. They said that the corals of Venezuela and Honduras, in the southwest part of the Caribbean, might not have had the same opportunity to rebound.

Why does this matter?

As water temperatures of the ocean continue to warm due to climate change, we will see more and more of these bleaching events that put stress on the relationship between corals and zooxanthellae. Studies like this are important in learning about the resiliency of the reefs, or how well they will be able to deal with environmental stress. Some zooxanthellae and their host corals are more sensitive to changes than other species, and understanding how these species will react to change will help us to better care for our reefs and enact laws that can protect vulnerable areas.

This study also demonstrates the power of citizen science. Utilizing students and the general public to gather data allowed researchers to get a bigger picture of what was occurring in both time and space, while also acting as an educational experience to engage these students in a real life research project.

Overall, this study helped us gain valuable insight to how corals react to temperature change and what we can expect to see in the future as global temperature continue to warm.

I am currently a Master’s candidate in Environmental and Ocean Sciences at the University of San Diego, and I study the stickiness of phytoplankton using 3D images. By tracking collisions of phytoplankton, I can see how sticky they are by observing how often they stay together when they collide instead of bouncing off of each other. When I am not working on my thesis you can find me on the beach, reading a book, or working on a painting!