Welcome to the underwater meadows

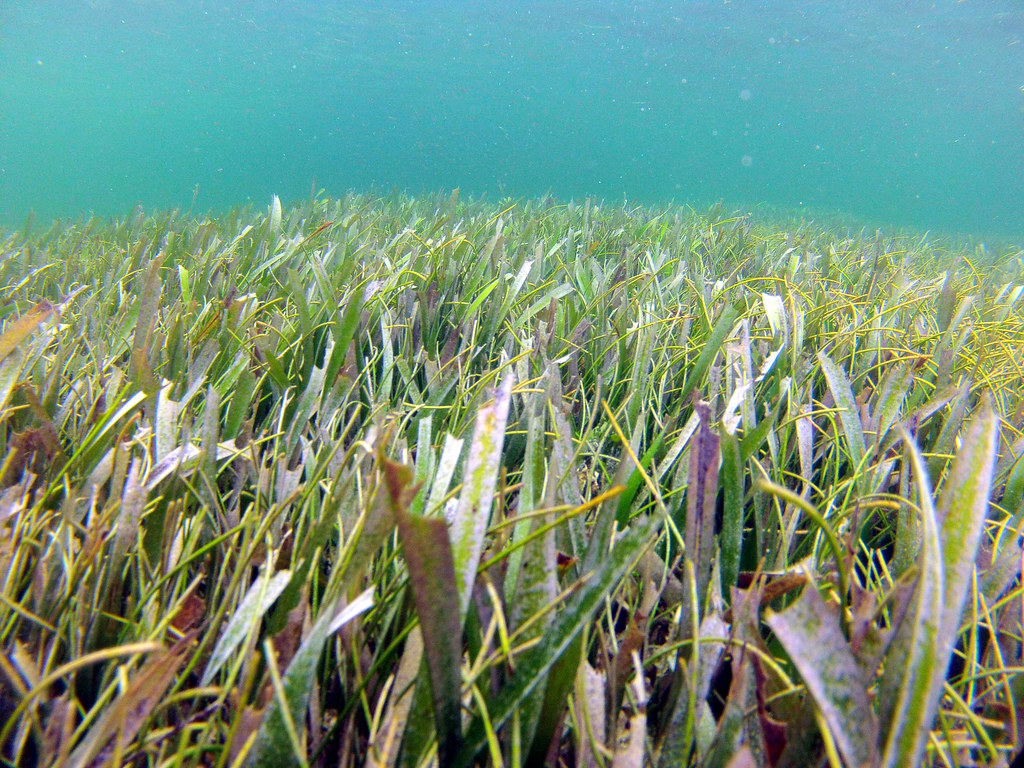

In temperate shallow waters around the world, seagrasses form massive, majestic underwater meadows. Gently swaying in the current like they’re about to set the scene for a Western movie, their long thick strands attract as many different sea creatures seeking habitat and refuge as terrestrial grasslands attract birds, insects, and mammals.

Seagrass communities play a vitally important role in coastal and estuarine marine ecosystems, providing habitat and shelter from physical disturbances to a variety of fish and invertebrates as well as storing massive amounts of trapped carbon.

While their high numbers attract foraging sea creatures, these communities experience fluctuations in salinity and temperature, important environmental factors which affect the growth and survival of seagrass communities. This is because certain organisms may not grow as well if these changes create stressful conditions. For instance, high salinities can cause changes in the overall productivity of marine ecosystems, because many species cannot survive at high salinities. Similarly, warmer temperatures can mean that seagrasses grow faster and that hungry invertebrates and fish can graze more intensely and potentially reduce seagrass abundance.

Herbivorous fish are a common resident in seagrass beds, chomping away on the seagrass leaves like a buffalo might graze the Prairies. Grazing by herbivorous fish can reduce the abundance of seagrasses, which can have profound impacts on the structure and health of seagrass meadows. However, exactly what effect this grazing has on the seagrass community is not well-understood. Furthermore, it is not clear how changes in salinity impact fish grazing in seagrass meadows. As our oceans move forward into climate change, it is likely that seagrass communities will experience alterations in salinity, among other factors. Therefore, understanding how salinity and grazing are currently affecting these communities is important as we navigate the waters into the future.

Shark Bay, Australia

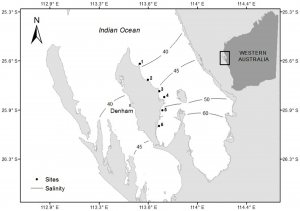

Sahira Bell and colleagues, of the University of Western Australia, investigated the impacts of grazing fish and their feeding choices on seagrasses in Shark Bay, a shallow coastal embayment of Western Australia. Shark Bay is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as it has important conservation values because it holds the world’s largest and richest seagrass meadows.

Shark Bay is characterized by a range of salinities that span normal oceanic levels (~3% salinity) at the north end of the bay that opens up to the Indian Ocean, to hypersaline conditions (>3% salinity) at the southern end due to high rates of evaporation and limited mixing with the north end. The seagrass meadows in Shark Bay are dominated by large stands of temperate species, but smaller patches of fast-growing tropical grasses are also present.

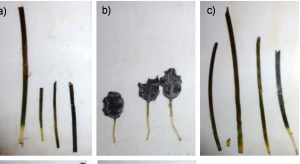

To investigate how fish grazing intensity changed across the range of salinities experienced in Shark Bay, the researchers monitored fish grazing pressure by attaching equal amounts of 5 common live seagrasses to ropes suspended on the seafloor throughout the bay. The researchers made sure that they offered the same amount and species of seagrasses at various sites that spanned the low and high range of salinity.

Before the seagrasses were tied to the ropes, the researchers photographed each seagrass so that after the experiment they could estimate how much of the seagrass leaf was eaten by fish. The researchers also set up underwater GoPro cameras so that they could see which fish species were grazing on the seagrass ropes.

Some fish are choosy eaters; Often, they will show a preference for seagrasses that have high nitrogen concentrations. Nitrogen is important for building proteins necessary for daily life. Similar to the protein and energy information we find on our cereal boxes, the researchers measured the amount of nitrogen in the leaves of the 5 seagrass species used in the seagrass ropes.

What did they find?

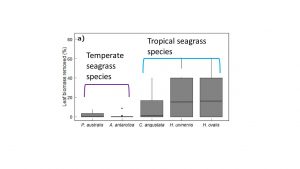

Bell and colleagues found that seagrasses were grazed most intensively at the lowest salinity, while virtually no seagrasses were eaten at the sites where salinity was highest. They also found that not all seagrasses were grazed equally; the tropical species were chosen more frequently than the temperate grass species.

Among the grazers caught on video, rabbitfish and Western striped grunter were caught on video eating seagrasses. The authors also found that the tropical seagrasses had more nitrogen than the temperate species, which may explain why these grasses were grazed upon more frequently than temperate grasses. This finding indicates that while less nutritious temperate species of seagrass dominate in Shark Bay, the fish sought out the less abundant, but more nutritious, tropical seagrass species.

So why does salinity have this effect? The fish in Shark Bay likely hang out in the less salty areas because higher salinity areas are stressful for them, making it difficult to graze effectively. While the seagrasses can survive throughout the range of salinities of Shark Bay, fish were restricted to grazing in the lower-salinity meadows. This means that changes in salinity can restrict or expand grazing fish in Shark Bay.

The bigger picture

Seagrasses play a vital role in marine food webs. A majority of research on seagrasses before this study emphasized the role of seagrasses as primarily habitat for invertebrates and fish, not necessarily as food. Therefore, this study shows that not only are seagrasses important for structuring ecosystems, they are important sources of energy for fish, particularly the more nutritious tropical species.

This study shows how environmental factors and grazers interact to influence seagrass communities. This is important, especially within the context of climate change. Indeed, warming water temperatures may lead ravenous fishes, such as the rabbitfish recorded in this study, to expand their range into other temperate seagrass meadows, where they could reduce seagrasses to the detriment of other species that depend on them, including sea turtles and marine mammals. Future studies will be necessary to understand how ocean warming will impact grazing fish populations, as these are important forces acting upon seagrasses.

Kate received her Ph.D. in Aquatic Ecology from the University of Notre Dame and she holds a Masters in Environmental Science & Biology from SUNY Brockport. She currently teaches at a small college in Indiana and is starting out her neophyte research career in aquatic community monitoring. Outside of lab and fieldwork, she enjoys running and kickboxing.