For the past few weeks I have been braving the wild seas in the middle of the Southern Ocean on board a U.S. Antarctic Program icebreaker, as part of a new and exciting research program to measure the chemical and biological properties of the Southern Ocean. We are southwest of the tip of South America at 55 degrees South, 90 degrees West where I am deploying instruments that will float in the ocean and collecting samples of seawater from the depths of the ocean. Today I will be sharing a little about the research program and my job as a scientist at sea.

Southern seas

The Southern Ocean is the vast ring of ocean that encircles Antarctica and is home to the strongest winds and ocean currents on Earth. Because of the unique geography of the Southern Ocean, it connects waters from the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic Oceans and is a site where deep ocean waters that are hundreds of years old come back to the surface and interact with the atmosphere. The Southern Ocean also dominates the uptake of heat and carbon dioxide into the global oceans, which makes it critically important for regulating our climate by removing heat and carbon dioxide, a potent greenhouse gas, from the atmosphere. Measuring and understanding changes in the Southern Ocean are key to understanding changes in our climate and predicting future change due to global climate change.

Due to the remoteness and extreme weather and ice conditions in the Southern Ocean until recently there have been very few direct measurements of the chemistry and biology of the Southern Ocean. The development of new relatively inexpensive ocean observing technology in the past decade has created exciting new opportunities for observing the Southern Ocean with much higher frequency.

A new opportunity

The Southern Ocean Carbon and Climate Observations and Modeling (SOCCOM) project aims to better understand the role of the Southern Ocean in global climate using a combination of a new observing system for carbon, nutrients and oxygen and state-of-the-art computer simulations of the Earth’s climate. The observations team is deploying a large array of floats (about 180) with biogeochemical sensors throughout the Southern Ocean, including regions covered with sea ice in the winter season. The floats are called profiling floats, which means that they measure ocean properties from 2000 m depth to the surface as they move up in the ocean, creating a profile of data. As well as the floats, some data is collected from ships, and the data is analyzed and entered into a computer model of the ocean (the Southern Ocean State Estimate; sose.ucsd.edu) to make it more accurate. The project is now in its second year and there are currently 33 active floats.

Floating robots

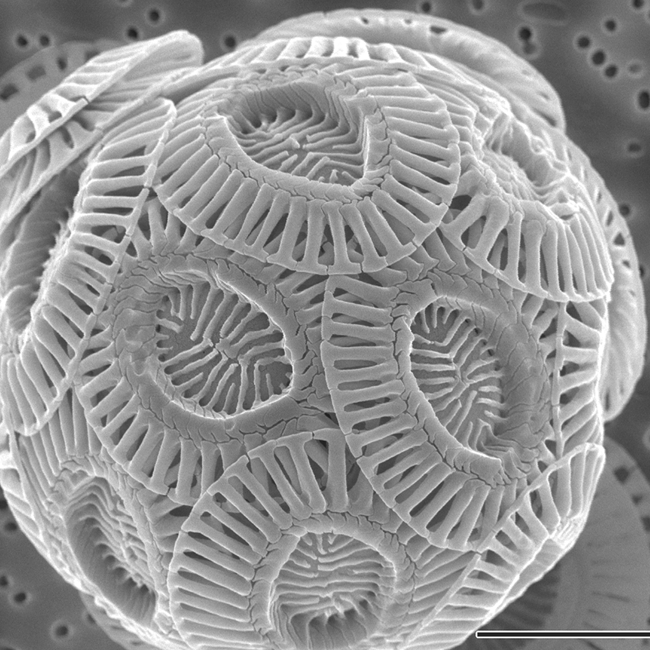

The SOCCOM profiling floats are closely related to Argo floats which are autonomous instruments about the size of a person which drift in ocean currents and control their buoyancy to move vertically in the ocean, collecting pressure, temperature and salinity data profiles with sensors mounted on the top of the float. The floats complete a profile once every 10 days, returning to the surface after each profile to send the data to a satellite and typically completing 200 profiles in their lifetime. As well as measuring temperature and salinity, SOCCOM floats are mounted with extra sensors to measure pH, oxygen, nitrate and some of them also have optical sensors to estimate the amount of phytoplankton growing in the water. This is important because phytoplankton are like plants on land, using nutrients and the suns energy to take up carbon dioxide by photosynthesis and produce oxygen. In the Southern Ocean the carbon dioxide absorbed by phytoplankton is an import process for the uptake of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. In the past the pH, oxygen, nitrate and optical sensors have been used mostly on ships so adding these to the floats will provide new and exciting information about the chemical and biological properties of the water in places that haven’t been measured before.

One key thing about the SOCCOM floats is that because the sensors are so newly developed, the first data they collect needs to be compared with water samples taken from a research ship. If there are differences, the float data may need to be adjusted to be consistent with the ship measurements that are the most accurate. This means that rather than just dropping the floats overboard, we need someone to go out in the Southern Ocean with the floats to collect and analyze water samples collected on a ship for calibration. Right now I am onboard the U.S. Antarctic Program icebreaker, the R/V Palmer, in the Southern Ocean to do just that.

SOCCOM at sea

The research cruise I am on is part of another project and I am working alongside the scientists and engineers on the ship to help out with their work and deploy and calibrate the SOCCOM floats. We are almost two weeks into the trip and I will be at sea for a month total, including Christmas and the start of the New Year until we return to port in Punta Arenas, Chile. Working in the Southern Ocean can be very tough because extreme weather can make it difficult to work. At the beginning of this trip we had with winds greater than 30 knots and waves up to 20 feet, making it impossible to do scientific work. Luckily, we have had enough of a break in the whether that I have successfully deployed the first of three SOCCOM floats and the float has reported its first profile of data to a satellite, which we receive back on land. I have two more floats to deploy on this expedition, and there will be another 20 SOCCOM floats deployed in other regions of the Southern Ocean this year and many more planned for next year.

Beyond the ship

The data coming back from the SOCCOM floats has already provided new insights into biogeochemistry in the Southern Ocean. For example, in the past there were no observations of the seasonal formation of a spring bloom of phytoplankton in regions that are covered with sea ice in the winter. Now we have multiple observations showing how the spring bloom develops rapidly in the spring after the ice melts. Beyond the science impacts of this project, we are partnering with Climate Central to provide outreach for this project and have hosted multiple public Google hangouts and are currently working with middle school students on a pilot ‘adopt-a-float’ program. You can read more about my journey in the Southern Ocean on my blog.

I’m a PhD student at Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla California. My research is focused on the Southern Ocean circulation and it’s role in climate. For my research I sometimes spend months at sea on ice breakers collecting data, and at other times spend months analyzing computer models.