Leeney, RH, Mana, RR, and Dulvy, NK. 2018. Fishers’ ecological knowledge of sawfishes in the Sepik and Ramu rivers, northern Papua New Guinea. Endangered Species Research 36:15-26. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00887

What if I told you sharks have cousins that are so morphologically distinct, they swim around sporting a toothy, chainsaw-like projection between their eyes, called a rostrum? Now what if I told you that largely because of that unique rostrum, these are some of the most endangered shark relatives in the world? Don’t lose hope! Scientists around the world are actively working to save sawfish before it is too late.

Background

The five species of sawfish, smalltooth (Pristis pectinata), largetooth (P. pristis), green (P. zijsron), dwarf (P. clavata), and narrow (Anoxypristis cuspidata) are among the most endangered elasmobranch species in the world. All sawfish species, excluding smalltooth sawfish, which are found mainly in South Florida, USA, and The Bahamas, can be found in northern Australia. Declines in all sawfish populations are attributed to both over harvest and habitat loss. Because of their unique morphology, sawfish were harvested as trophies to display their rostrum (plural rostra), or saw. Sawfish were also harvested for their fins and meat. Additionally they also experience high bycatch mortality. Bycatch is the catch of non-target species in a fishery. Juvenile sawfish rely heavily on shallow, mangrove lined coasts for protection from predators and abundant food. The loss of mangroves due to coastal development has also contributed to population declines. Currently all species of sawfish are protected under Appendix I of CITES, which prohibits international trade of live sawfish and sawfish parts.

Introduction

Despite being separated from Australia by only a short, shallow stretch of water, the current state of sawfish populations in Papua New Guinea is relatively unknown. Largetooth sawfish were first reported in Papua New Guinea in 1929. A recent study at a single site in Papua New Guinea found that all four species present in Australia were also found on the southern shores of the island (White et al. 2017). This means that Papua New Guinea could be an important stronghold for four out of the five critically endangered sawfish species. Armed with this information, Dr. Ruth Leeney and her team set out to remote villages in northern Papua New Guinea to interview local fishermen about sawfish in their area. The goal of their study was to rapidly assess the state of critically endangered sawfish populations in a region where data was lacking.

Methods

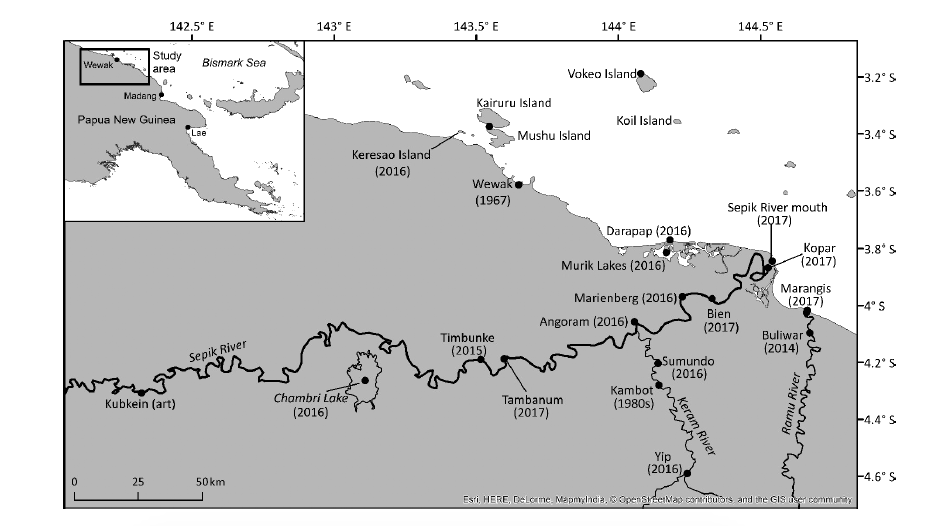

Leeney and collaborators conducted interviews of both male and female fishermen in villages primarily along the Sepik River in northern Papua New Guinea. The river mouth is host to several small-scale fisheries, including a shark longline fishery. Within the river, artisanal fisheries operate for subsistence. Interviewees were shown a photograph of a sawfish and asked if they recognized it and knew what type of fish it was. If they could identify the sawfish, they were asked subsequent questions about recent and historical sawfish sightings and captures as well as the cultural or economic importance of sawfish.

Results

Of the 46 fishermen interviewed, all but one had encountered a sawfish, primarily while fishing with nets. The majority of fishermen fished from the river out of wooden canoes with wooden paddles, as opposed to an outboard motor. Over half of the interviewees had seen sawfish more than 10 times, and 84% had seen at least one sawfish in the last seven years. Sawfish catches were reported along the entire length of the Sepik River to Chambri Lake where surveys stopped due to difficulties traveling farther upriver. Forty-two individuals reported seeing sawfish more than three times during their lifetime and were consulted further on trends in abundance. Most local fishermen believed that sawfish populations were declining, and cited increased fishing effort with nets as the cause.

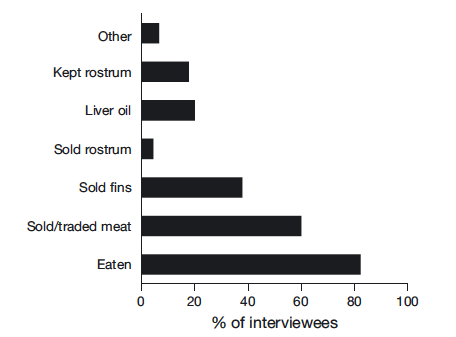

Perhaps unsurprisingly due to the nature of the fishery, over 80% of interviewees reported that sawfish were harvested for meat. Sawfish meat was either eaten directly by the family that caught it, sold, or traded for vegetables at local markets. A third of individuals sold sawfish fins, but some were not aware of the

fins’ value and discarded them. Those that sold fins reported earning as much as $110 per fin, while the meat was much less valuable. Surprisingly, only four interviewees reported saving or selling rostra and rostra were generally considered to have no economic value. One way to differentiate sawfish species is by the tooth count, placement, and morphology along the rostrum. Based on rostra observed during the surveys both narrow and largetooth sawfish are present in the Sepik River. While conducting interviews, the research team confirmed this when they observed the catch and release of two juvenile narrow sawfish and a recently harvested largetooth sawfish.

Conclusions

This is the first study to document contemporary sawfish populations in northern Papua New Guinea and shows that at least two species of sawfish occupy an extensive amount of the Sepik River. There are indications that the mouth of the Sepik River may be an important nursery area for juvenile sawfish, making them particularly vulnerable to capture in the small-scale shark fishery that operates there. Though sawfish are protected under CITES, their fins have been documented in exports from Papua New Guinea. Additionally, many of the interviewees were subsistence fishermen, relying on their catch for food, which poses a conservation challenge when mandating that these endangered fish are released alive. Education of both local fishermen and customs officials about the identification and conservation status of sawfish will be vital to protect these endangered species.

In addition to Australia and the United States, Papua New Guinea now appears to be the third country documented as a sawfish stronghold. This would not have been possible without the knowledge of local fishermen, and highlights the value of using local knowledge for conservation. Further research to better understand population size and essential habitats for each species present, along with strong community collaboration, will be essential to save sawfish in Papua New Guinea.

Further Reading

For more information on sawfish in the United States, check out NOAA’s overview of smalltooth sawfish.

Interested in more sawfish research? Check out the Sawfish Conservation Society!

I am currently a Marine Science and Technology Doctoral student at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. I use acoustic and satellite telemetry to study the spatial ecology of lemon, nurse, Caribbean reef, and tiger sharks in St. Croix to better understand habitat selection, residency, and connectivity between the protected areas and areas open to fishing. I am broadly interested in the intersection of marine animal movement, particularly elasmobranchs, with fisheries management. In my free time you can find me curled up with a good book and a cup of tea or outside exploring with Deacon, the goofiest Irish setter in Massachusetts.