Crump A, Mullens C, Bethell EJ, Cunningham EM, Arnott G. 2020 Microplastics disrupt hermit crab shell selection. Biol. Lett. 16: 20200030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2020.0030

Microplastic intrusion

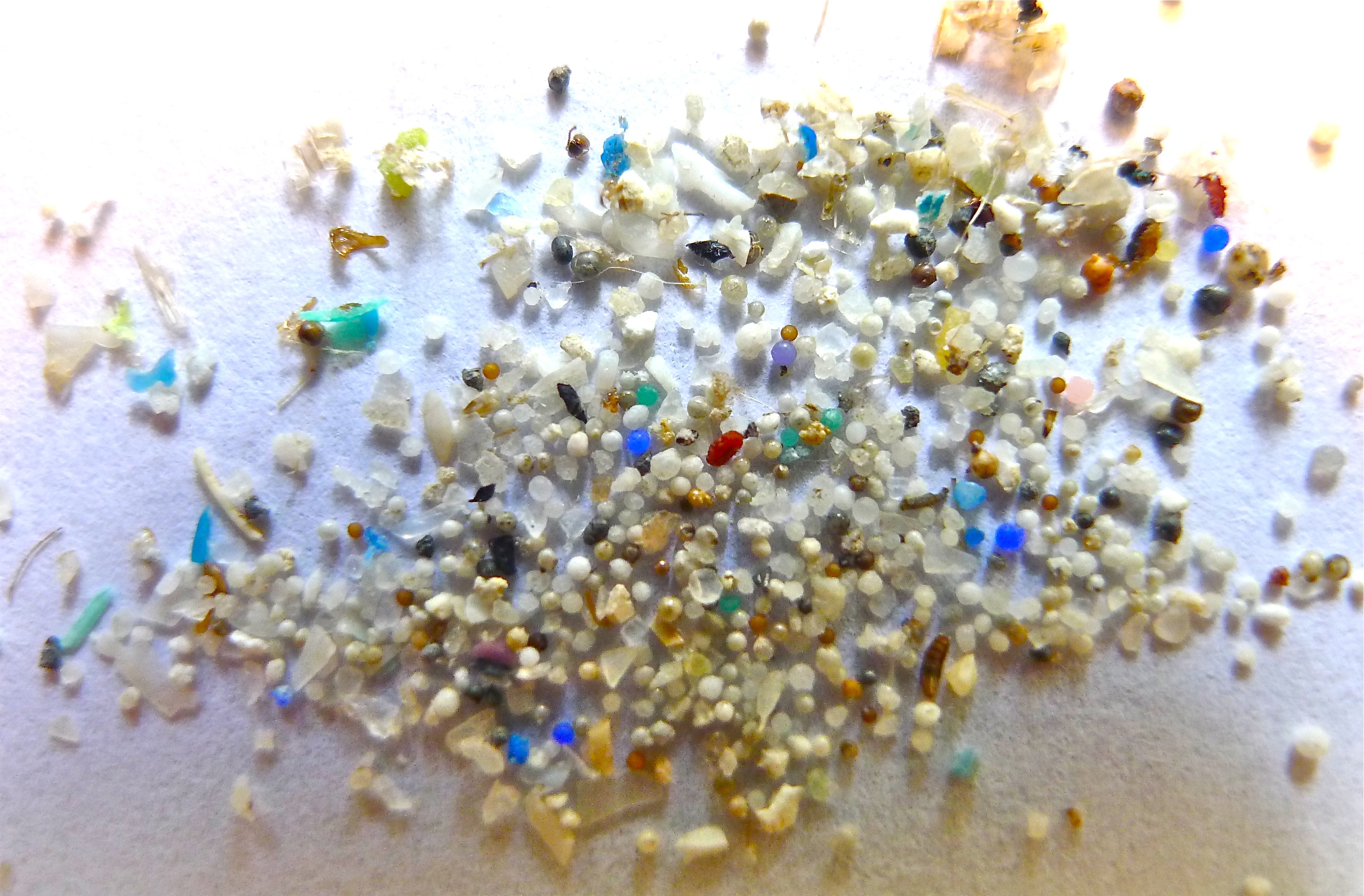

Tiny plastic particles of varying shapes and sizes saturate waters from the depths of the ocean to its sandy shores. These microplastics can infiltrate the bodies of marine animals, disrupting their lives in ways we are still only just beginning to understand.

Many of these microplastics have spent a lifetime breaking down. Minute plastic fragments may start off as full-sized water bottles or plastic packaging or any number of other pieces of plastic which were disposed of but which in reality found their way into the sea. Very slowly, plastics are weathered by ocean waves and the sun’s intense UV rays, getting smaller and smaller without disappearing altogether. While some microplastics are fragmented bits of larger objects, others are microbeads or tiny pellets intentionally manufactured to such a small size. Regardless of their origin, microplastics are gradually becoming ubiquitous within the world’s oceans and their inhabitants.

It seems intuitive that tiny plastics making their way into an animal’s body would have negative physiological impacts – animal bodies, their organs and tissues, were never intended to encounter these unnatural bits and pieces of plastic which take so long to decompose. But how might microplastics affect an animal’s behavior and cognition, their ability to gather information and make decisions?

Hermit crab shells

In a recent study, scientists investigated this question by looking at how hermit crab shell selection is impacted by exposure to microplastic-filled water. To conduct their experiment, researchers collected European hermit crabs from the beaches of Northern Ireland. This species, and all other species of hermit crabs, must change shells as they grow, and choosing an optimal shell is essential for survival.

When a hermit crab encounters a shell, they assess the inside and outside, collecting information in order to determine if the shell is adequate, to decide whether it is time to leave their current home and move into a new one. Hermit crabs use their small claws, called chelipeds, to inspect a new shell, exploring whether it might be worth a move. This process requires proper cognitive functioning; in order to accurately assess the shell, the crab must be able to collect and process information before making a decision. Would hermit crab shell selection and cognition still function the same when subject to microplastic pollution?

It looks like the answer, based on the scientists’ experiments, is no.

Impaired shell swapping

The researchers placed hermit crabs in suboptimal shells before putting them into a tank and giving them the option of a new, better shell to move into. Half of the crabs tested were placed into microplastic-laden water, while the other half were not exposed to any microplastics. As part of their experimental design, the researchers made sure that the levels of microplastics they exposed the hermit crabs to mimicked the amount of plastic they might encounter in a natural setting. This is different from past studies, which often exposed marine organisms to higher concentrations of microplastics than those found in most coastal habitats.

Hermit crabs which were exposed to microplastics touched the new shells less frequently, took longer to come into contact with the new shell, spent less time assessing the shell, and swapped suboptimal for optimal shells less often than their counterparts in the control experiments.

More research is necessary to figure out exactly what changed the hermit crab’s behavior and ability to select a better shell, but the authors of this recent study suggest that it may have been due to changes in energy levels after ingesting microplastics. The microplastics used in this study were likely too large to have entered the bloodstream and made their way to the brain where they could impact cognitive processes directly. Since this study’s microplastics were used because of their similarity to those found in the crab’s natural habitat, it seems unlikely that the brain would be directly impacted in the wild, either.

What may have happened instead is that the crabs’ brain functions were impaired by decreased energy levels brought about by consumption of microplastics. When marine organisms consume microplastics, they feel full even though they have consumed particles which don’t provide them with any nutrition. They then stop eating, but the lack of nutrients means that their body is not getting the energy that it needs to get from finding food. Decision-making by the brain requires adequate amounts of energy, something which a crab with a stomach full of microplastics cannot provide.

Cutting down on plastics

Survival in the ocean is a difficult task, involving everything from searching for food to finding the perfect shell for protection from predators. With more research, it’s becoming more and more evident that microplastics and a variety of other forms of pollution can impact all of these different aspects of survival for a marine organism. In order for organisms to continue to survive and thrive in the ocean and around the globe, we need to cut down on microplastics at the source, reducing plastic production and usage before it finds its way beneath the waves.

I am a PhD candidate at Syracuse University studying marine mammal communication. My research focuses on analyzing underwater recordings of whale calls in order to better understand whale behavior. I’m also interested in education, outreach, and science communication. When I’m not listening to whale sounds, you can find me curled up with a good book or complaining about how much it snows in Syracuse.