Stoicescu, S.-T., Laanemets, J., Liblik, T., Skudra, M., Samlas, O., Lips, I., and Lips, U.: Causes of the extensive hypoxia in the Gulf of Riga in 2018, Biogeosciences, 19, 2903–2920, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-19-2903-2022, 2022

Do you ever wonder what happens to the water in your pipes when it leaves your house? Or what about that extra fertilizer you spread on your lawn? In developed countries, water from our homes gets carried to a wastewater treatment plant that cleans the water before it is released back into the environment, often into a river or bay. As for the fertilizer, rainwater from storms can carry the fertilizer into sewer drains or directly into a nearby water body. Even though we have improved our wastewater and stormwater cleaning practices over the years, some of those pollutants still make it to the coast. So what happens when that water gets into a bay?

Making “dead zones”

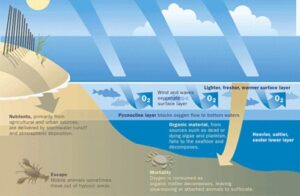

Water from runoff and wastewater are full of nutrients, such as nitrate and phosphate, that can cause algae growth when released into the water. After the algae die, they sink and get eaten by bacteria that suck the oxygen out of the water. When this happens, fish and other small animals can die because they do not have enough oxygen to breathe. This is how we get ocean “dead zones”!

An algae bloom, seen in the bottom portion of the photo, off the coast of Texas. Photo from NOAA.

“Dead zones” are common near the coast because these areas are highly populated, so there is lots of wastewater and runoff filled with nutrients entering the coastal ocean. There is also freshwater from rivers entering the ocean near the coast- this freshwater is less dense than salt water and therefore floats on top of the salt water, creating two separate layers. Warmer water is also less dense than cold water, so hot summer temperatures can also help to create distinct layers within the water column. This process is termed stratification, and stratification of the water column decreases mixing, meaning even less oxygen can get into the water. This often happens in summer, after spring rains bring in lots of freshwater and higher temperatures heat the water. All these factors combine to make “dead zones” that can last for months if conditions are right!

Diagram depicting the creation of “dead zones”, adapted from CC BY 2.0.

The fate of “dead zones”

Recently, researchers studied the “dead zone” that formed in the summer of 2018 in the Gulf of Riga, a semi-enclosed region of the Baltic Sea. The summer of 2018 saw one of the largest “dead zones” in the area since sampling began, and researchers wanted to know why this year was so bad and if the “dead zone” will get bigger in the future. Their hypothesis was that exceptionally warm temperatures that year decreased water mixing and larger winter storms produced more river flow and runoff, adding more nutrients to the Gulf.

The scientists used previous data collected on the water column in the area, including nutrient concentrations, bottom water dissolved oxygen, salinity, and temperature to understand how these factors changed over time. They also used previously collected data to understand how surface temperature, rainfall, and wind in the area changed over time.

Researchers found that the “dead zone” in this area is getting bigger over time, as is the case for many other coastal areas. In the summer of 2018, particularly hot temperatures and weak winds decreased mixing of the water column, lowering the amount of oxygen that could get into the bottom layer of the water. These factors led to a stratified water column that caused a “dead zone” until temperatures cooled and the water mixed in the late Fall of 2018.

What’s next and how can we help?

Scientists predict that “dead zones” will spread in the future as climate change gets worse. Climate change will bring hotter summers, meaning more water column stratification and less mixing of oxygen into the water. If we want to prevent “dead zones” from spreading, we can first reduce the amount of nutrients getting the coast. There are many ways we can all help- reduce fertilizer use, clean up after your pet, and plant a rain garden. But ultimately, we must also combat climate change to ensure “dead zones” will not continue to wreak havoc on our coastlines years into the future.

Cover photo: algal blooms in the Gulf of Mexico, credit “eutrophication” by NOAA’s National Ocean Service , Public Domain Mark 1.0.

I am an MS student in Chemical Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography. My research focuses on biogeochemical fluxes of nutrients both in the water column and in sediment. I am interested in how nutrient fluxes change in response to low oxygen conditions. Prior to graduate school, I received a BS in Environmental Science and a BA in Biology from the University of Vermont. In my free time, I like to ride my bike and drink good coffee.