Vacquié-Garcia, J., Lydersen, C., Lydersen, E., Christensen, G. N., Guinet, C., & Kovacs, K. M. (2021). Seasonal habitat use of a lagoon by ringed seals Pusa hispida in Svalbard, Norway. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 675, 153-164.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a ringed seal in the Arctic must be in want of sea ice (to lay on, that is). While the image of a starving, sickly polar bear has become a symbol of climate change in the Arctic, it is hardly the only species that relies on sea ice. Seals are yet another charismatic mammal that needs the frozen sea to get a bit of R and R, but also to raise their young. As sea ice dwindles, where will these rotund, blubbery, beauties go? Maybe to a cool lagoon.

Lagoons in Norway – Cool, but not like Laguna Beach

Lagoons are shallow, partially-sheltered pools linked only partly to the sea. The ice in the lagoons is frequently visited by seals, and Svalbard, Norway, provides some prime seal real estate. Seals rely on sea ice for many things, yet sea ice has started to become scarce, especially during the summer. In the Barents Sea, the summers (periods of minimal ice) extended by an average of 42 days between 1979 and 2013. At the same time, the glaciers in Svalbard have retracted, a trend that could add more lagoons to the 127 that already speckle the Svalbard coastline. This means that the seals’ usual sea ice in the open water is disappearing just as the number of lagoons increases. But can the expansion of this territory help the seals as they adjust to climate change?

Researchers are hopeful about lagoons for several reasons. Since water in the lagoons is both fresher than the ocean and protected from waves, sea ice forms in the lagoons earlier in the season and lasts longer than at sea. Important prey species, like polar cod and Arctic charr, are also found in lagoons. So far, ringed seals don’t appear to adapt well to the changes that have been happening in the ocean – they are found fewer and fewer places and stick to regions that most closely resemble the Arctic before climate change. However, with sheltered sea ice and some tasty food, lagoons could provide an important refuge.

Catch, tag, and release

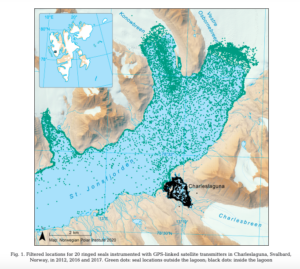

To observe how ringed seals use lagoons, the researchers caught 20 seals, attached a satellite-linked GPS tracker to their fur, and released them back into the lagoon. The trackers not only marked the location of the seals, but also if they were on land or in water (wet or dry) and how deep they dove when hunting. When the seals molted the next year (getting all new fur and marking the end of the breeding season) the trackers fell off.

Summer in the lagoon

Ringed seals did use the lagoons, but their behavior changed over the seasons. The seals visited the lagoon from July through February, but not at all in March through May. During spring, they gathered on ice outside the lagoon to mate, raise their young, and then molt. In general, they spent the most time in the lagoon from late summer through fall, with each trip to the lagoon lasting 21 hours on average, a seal’s day trip.

The seals appeared to get most of their food outside of the lagoon, spending 57-70% of their time diving. In the lagoon, however, seals had a more relaxed pace. Seals spent less time diving and more time laying around or swimming at the surface. When they did dive in the lagoon, it was more shallow and for less time than dives outside the lagoon. However, food availability in the lagoon was still important. The seals spent 14-38% of their time in the lagoon diving, especially during autumn and winter to make up for the energy used in breeding and molting.

The call of the sea

There is still much we don’t know about the lagoons in Norway, from the way different species use lagoons to how deep these lagoons are. This study is just a first step to determining how lagoon ecosystems will be used by Arctic species during climate change. However one thing is clear: ringed seals are still very reliant on sea ice outside of the lagoons for breeding and feeding. This is likely due less to preference and more practicality. Especially after pups are born, seals need to eat a lot to remain healthy. Researchers don’t yet know how much food is available in the lagoons, but it likely isn’t enough. The lagoons can offer a respite when sea ice is hard to find, but it doesn’t appear to provide all the bread and butter.

The IPCC says that the amount of Arctic sea ice is declining at a rate of 13% per decade, and by 2040 the Arctic could have ice-free summers. This is bad news for many species, including polar bears, walruses, and sea birds, not just seals. No matter how much more sea ice is in the lagoons, for now ringed seals will continue to respond to the call of the sea. The best we can do is try to ensure that some sea ice remains for them, even if they like to daytrip to the lagoons.

I am a PhD student studying Biological Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography. My interests are in food webs, ecology, and the interaction of humans and the ocean, whether that is in the form of fishing, pollution, climate change, or simply how we view the ocean. I am currently researching the decline of cancer crabs and lobsters in the Narragansett Bay.