Alien species are a commonly known and growing global concern. Increasingly transported to new locations and often following significant and increasingly widespread environmental degradation in their new homes, it seems more and more aliens are making the transition from visitor to invasive species. Some invaders, usually predators, can become particularly competitive and contribute directly or partially to the decline of native species in their new ranges. Others affect water quality and drainage in human environments while still others can decimate important crop and lumber species. Because of the threats they pose to native ecosystems and human interest, nearly every country has a list of invasive species prioritized for management and strategy for combating them.

Island nations are particularly wary of aliens. Islands are interesting microcosms of ecology, where the colonization of a new species and the extinction of existing species can both happen very quickly. This happens because islands may be small in geographic size, have few species to begin with, have less habitat options (or potential for different niches), or are far from sources that might replenish their population, like the mainland. For existing species, this means island life can promote very fast and incredible speciation, like Darwin’s classic finches, as well as extinction of varieties that can no longer compete with their quickly-changing neighbours. For new species, it means islands present ripe territory for the taking – given the right conditions.

Toral-Granda et. al. published a study recently in PLoSOne that attempted to profile the many pathways aliens have taken to arrive in the Galapagos, a well known hotspot of unique native biodiversity. They ask:

- How did the species that have arrived since permanent human settlement get to the islands?

- Has the importance of these particular pathways changed over time? and,

- What can we do to strengthen our biosecurity efforts given this information?

These questions are important to answer; invasive species are thought to be the greatest threat to native diversity on the Galapagos. When Darwin made his iconic trip to the Galapagos, the islands were unsettled and only rarely visited by then-warring Spanish and English naval vessels. Back then, the plant and animal life were relatively wild and only the first few invaders, rats, had become established on the islands. Aquatic iguanas, giant tortoises, blue footed boobies, tiny penguins, and a host of other strange and wonderful life forms greeted Darwin when he first inventoried the islands. Many of these are threatened today. But the fascinating plants and animals Darwin encountered in the 1800s weren’t always there.

The islands together make up an archipelago, fed by underwater volcanoes that have been slowly erupting for what might be thousands of years. Volcanic islands like the Galapagos, Hawaii, Sumatra, and Java, are fascinating study subjects for biologists, because they are essentially created from scratch. The tough rock that results from cooling magma at the ocean surface doesn’t immediately support life. Life has to arrive there, sometimes from many kilometre-long migrations from the mainland. The Galapagos Islands are nearly 1000km from the nearest point on the mainland in Ecuador; for life to establish here, it had to be pretty hardy. Many of the earliest plants to colonize new oceanic islands produce seeds that float or can be carried by far-travelling birds. Not surprisingly, the first animals are often birds and marine invertebrates like snails and crabs. In time, rotting plant and animal matter creates soil and less hardy species can move in, transported via floating logs or in the fur or feathers of animal carriers. Slowly but eventually, complex ecosystems form, supporting a diversity of life found potentially nowhere else in the world. The problem with adding new species to island ecosystems nowadays is the rate at which it’s happening.

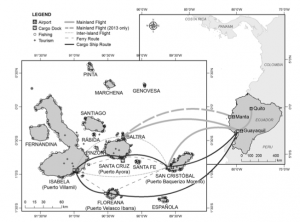

The biggest reason for the increasing pace of alien introductions around the world is the increased rate of movement of people (and their goods and products). Trade-related transport, the movement of food, wood, and other products are usually the biggest culprits, but tourism activity can transport potential invaders as well. Tourism is one of the largest and fastest growing sectors of the global economy. The Galapagos have only been permanently inhabited since 1832 and tourism only became prominent in the late 1970s, but it has since become a staple of the island’s economy. With more and more people living on and visiting the island, and the number of transport vessels increasing, the Galapagos has gained a considerable amount of new species over a short time span. In response to growing global concern over the risks of alien species, the Ecuadorian government adopted new biosecurity protocols and lists of prohibited and controlled goods and products. They followed with a strategic plan and dedicated biosecurity agency in the early 2000s. To date, and despite lengthy and costly efforts on behalf of the Ecuadorian government, only four invasive species have been eradicated.

Toral-Granda et. al. found that 1,579 alien species have been introduced to the Galapagos by humans to date. 1,476 of these (~93%) have successfully established viable populations. Half of these successful invaders were intentional introductions, mostly plants (garden varieties), and more than half have become naturalized with self-sustaining populations in Galapagos National Park. Unintentional introductions tended to be associated with the transport of plant-based or plant-derived goods and products. The rest were introduced directly by the transport vehicles themselves. About 37% of the established species seem to be dependent on humans for survival or are limited to areas with significant human settlement and do not appear to be spreading – or actively invading natural habitats.

When managing alien species, scientists try to understand both the natural tendencies of species in their home ranges and factors that might affect their success in a new environment. This might include competitiveness of the species in its original environment, relationships with its predators and prey, average reproductive success, how much space there is in the new environment, the presence of similar predator/prey species, etc… All of these factors play a role in determining the likelihood of establishment, invasiveness, and detrimental effects in the new environment. For many species, these details are difficult if not impossible to confidently describe and the aliens that do establish are incredibly varied in taxonomy and original location on the globe. Ultimately, the biggest guarantees that an alien will become established in a novel habitat are frequency of introduction and how fast the species can hit the ground running (basically, have a lot of healthy babies). Whether or not newly established species will become a problem is another question.

Toral-Granda et. al. suggest that pathways of invasion be added to alien management discussion. Not only are alien species finding new ways to the islands (and probably the mainland as well), but Toral-Granda et. al. showed that different pathways can transport different kinds of aliens. Considering the variety of transport mechanisms available to aliens and the growing number of places they come from, we may soon see trends in what pathways produce the most or worst invaders. If the aliens are here to stay, and it looks like they are, it’s important that scientists are able to prioritize them for management in a comprehensive and informed way. Transport pathways may be one of those informing factors.

Article: Toral-Granda MV, Causton CE, Ja ̈ger H, Trueman M, Izurieta JC, Araujo E, et al. (2017) Alien species pathways to the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. PLoS ONE 12(9): e0184379.

https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184379

Hi! I’m Rebecca Parker. I’m an ecologist and plant lover working in non-profit conservation in Nova Scotia Canada. I trained at Dalhousie and Ryerson University, where I completed a Masters in Environmental Science and Management. I like botany, wetlands, and wetland botany! On the sciencey side, I like to write about current topics in population and community ecology, but I’m also really interested in environmental outreach, how exposure to science and demographics affect environmental values and behaviours, and best practices for building community capacity in environmental stewardship. Check out my instagram for photos of the awesome nature I see through my work.