Pratt Jr. HL, Pratt TC, Morley D, Lowerre-Barbieri S, Collins A, Carrier JC, Hart KM, Whitney NM (2018) Partial migration of the nurse shark, Ginglymostoma cirratum (Bonnaterre), from the Dry Tortugas. Environmental Biology of Fishes 101(4):515-530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-017-0711-1

If I asked you to name a migrating shark, you might list pelagic ocean rovers like the white (Carcharodon carcharias), shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus), or maybe even the filter feeding whale (Rhincodon typus) shark. I would be willing to bet that no one would say “the nurse shark of course!” With their new paper, long-time nurse shark researcher, Harold “Wes” Pratt, and collaborators are here to change that perception. Nurse sharks are homebodies no more!

Background

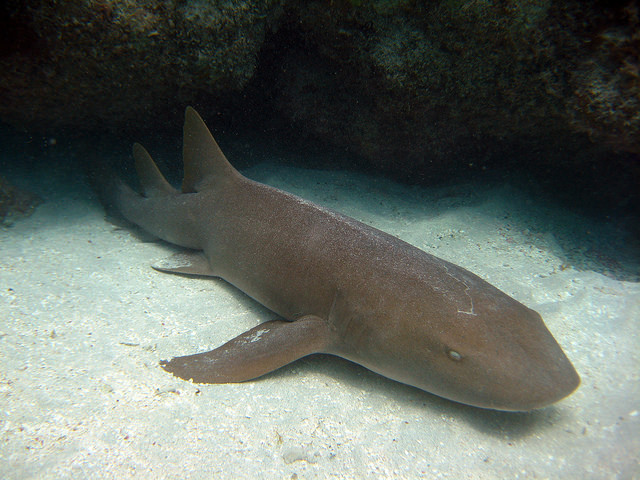

Nurse sharks (Ginglymostoma cirratum) are a tropical and sub-tropical large coastal shark species that range in the Western North Atlantic from the Carolinas, through the Caribbean, to Brazil. They are one of the most common shark species within their range, with high abundance in both South Florida and Caribbean shark communities. They are also famous for their site fidelity, meaning they spend most of their time in one, relatively small place. Traditional tag-recapture studies, where sharks are caught, tagged with small uniquely numbered external tags, and released with the hope of catching the shark again in a new location, have shown that nurse sharks rarely move far from home.

This is particularly true in the Dry Tortugas, FL, where adults seasonally aggregate to breed in June. Conventional tagging and recapture of nurse sharks, both adults and juveniles, in and around the Dry Tortugas Courtship and Mating Grounds (DTCMG) has been ongoing since the 1980s. Recaptures in the Dry Tortugas occurred throughout the year, leading researchers to reasonably believe that adult nurse sharks mating in the Tortugas are year round residents to the area, making individuals easily protected by closing the area to fishing.

Study Goals

Since nurse sharks are one of the most abundant shark species in South Florida and the Caribbean, it is important for fisheries managers to understand their movements to make sure conservation measures are effective. In this study, Pratt and collaborators set out to document the movements of nurse sharks in the Dry Tortugas using acoustic telemetry.

Methods

Because of their high site fidelity, nurse sharks are infrequently tagged with electronic tags that allow for more detailed tracking of fish movements. In addition to a traditional external tag, Pratt and collaborators tagged 57 adult nurse sharks with electronic acoustic tags from 2005 – 2014 to track their movements using acoustic telemetry. Acoustic telemetry works using a combination of tags and receivers. The receivers are anchored in areas where you are interested in tracking tagged animals. They can be thought of as listening stations, anchored in the water waiting for a tagged shark to swim within their range. The acoustic tags send out a “ping” every few minutes. When a tagged shark swims within the range of a receiver, the receiver registers the ping and records it. Researchers can then download the data from the receiver, giving them information about what sharks visited the receiver and when.

Results

After a female nurse shark conventionally tagged in the Dry Tortugas was recaptured 81 miles north in the Gulf of Mexico, researchers decided they needed to investigate acoustic tracking data in areas beyond the Tortugas. With the use of the iTag acoustic telemetry network the scientists were able to document long distance migrations of adult nurse sharks in areas beyond the Dry Tortugas.

They found that starting in 2011, eight sharks were detected outside of the Dry Tortugas in areas as far north as Charlotte Harbor (159 mi away) and Tampa Bay (208 mi away) on the west coast of Florida from April to December. Three males left the DTCMG in June or July, following the courtship and mating season arriving along the west coast of Florida in late July and staying through September. These males traveled up the coast quite efficiently, moving 186 mi north in as little as 18 days. Can you imagine running ten miles a day, 18 days in a row? Males often migrated to the same areas in late summer and fall before returning to the Tortugas to mate the following June. One male has been documented making the annual migration SIX times since he was tagged in 2010!

Not to be outdone, females, who only reproduce every two or three years, were also detected on receivers hundreds of miles away from the Dry Tortugas. On alternate years, five female nurse sharks were detected anywhere from 115 – 208 mi away from Boca Grande to St. Petersburg, FL. They left the Tortugas in April and May and most returned to the Tortugas soon after the end of the mating season in July. Females swam north even faster than males, covering 201 mi in 17 days! Most females were observed migrating in the second, third, or fourth year after they were tagged during mating season and spent the winter pregnant in the Tortugas. Assuming successful mating, the migrating years would correspond with the resting year for females who have recently pupped and are not yet ready to reproduce again.

Why does it matter?

Pratt and collaborators documented the first evidence of nurse shark migrations! Prior to this research, nurse sharks were considered a species that only exhibited localized movements. Their research clearly shows that nurse sharks are capable of directed, long distance swimming. They can swim against strong currents and exhibit homing, regularly returning to the Dry Tortugas after migrating north.

Though they do not know exactly why nurse sharks migrate, the authors think their migrations are driven by food availability and/or avoiding courtship behavior. Nurse sharks are still relatively slow sharks, and they may not be able to compete with faster predators for food, particularly in resource-limited areas

like the Dry Tortugas. After mating, mature males may be migrating to estuaries like Charlotte Harbor and Tampa Bay in search of abundant food sources. The female migration patterns clearly show an attempt to avoid mating and courtship behaviors. Shark reproduction involves a lot of teeth. Males often bite the female’s pectoral fins for leverage. To avoid unnecessary injury, females who are not ready to mate that season would have to constantly swim away from the advances of interested males, wasting a lot of energy. It may be better for these females to migrate away from the area than deal with interested male sharks. The females that left the Tortugas did so in April or May, avoiding the busy mating season in June.

Nurse sharks are the most abundant large shark species in the greater Caribbean, making them important predators in coral reef ecosystems. While not all individuals migrated, this partial migration means that we currently do not know the size of an adult nurse shark’s home range. This makes nurse shark conservation more challenging. This research shows that nurse shark populations are likely not effectively conserved by small area closures alone. During their migrations, nurse sharks encounter diverse habitats and a variety of human-caused stressors, from pollution to fishing gear. The authors conclude that further research on seasonal movements of nurse sharks throughout the Western North Atlantic combined with fisheries and coastal zone management are needed to best conserve this valuable, but underappreciated species.

I am currently a Marine Science and Technology Doctoral student at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. I use acoustic and satellite telemetry to study the spatial ecology of lemon, nurse, Caribbean reef, and tiger sharks in St. Croix to better understand habitat selection, residency, and connectivity between the protected areas and areas open to fishing. I am broadly interested in the intersection of marine animal movement, particularly elasmobranchs, with fisheries management. In my free time you can find me curled up with a good book and a cup of tea or outside exploring with Deacon, the goofiest Irish setter in Massachusetts.