Reference: Li, Bowen, et al. “Fish Ingest Microplastics Unintentionally.” Environmental Science & Technology (2021). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c01753

Pesky Plastic Pollutants

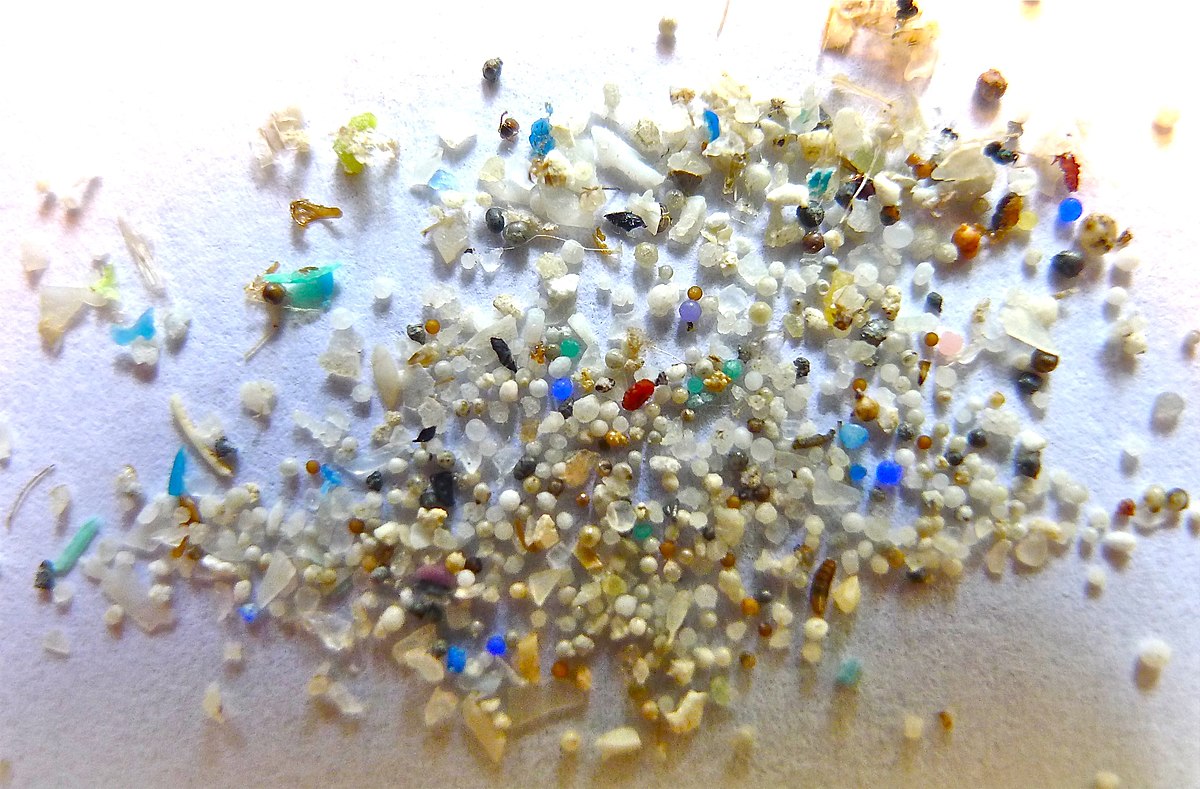

Microplastics (plastic pieces less than 5mm in size) are becoming an increasingly worrisome problem in the ocean. Small plastic particles can come from a variety of man-made products – from clothing, to car parts, to single-use plastic bottles. As these particles get into the ocean, they are taken up by plankton and fishes, and work their way up the food chain. From there, since microplastics end up in the seafood that humans eat, they end up in the lining of human intestines. While many studies (and previous oceanbites articles) have focused on the amount of microplastics that can be found in fishes and humans, not much research has been conducted on how microplastics may end up inside fishes in the first place. Are fishes actively eating these particles, or do they try to avoid them? Do different types of fishes interact with microplastics differently? To try to get at these questions, researchers from the State Key Laboratory of Estuarine and Coastal Research in Shanghai, China got to work.

Pellets and Fibers

The researchers studied four different fishes that use several different feeding methods: largemouth bass and yellow catfish that directly swallow prey, goldfish that suction feed, and bighead carp that filter feed. These four fish species went through several different feeding trials in order to determine how they interacted with micropellets, which are small round microplastic balls, and microfibers, which are thin, long strands of microplastic. The microplastics were placed in the fishes’ water with and without food, and fishes were observed when near the microplastic particles.

The bighead carp, the filter feeder in this experiment, did not show interest in any microplastic pellets regardless of whether food was also present or not. The swallowing fishes, the largemouth bass and yellow catfish, attempted to eat the most pellets, while the goldfish, the suction feeder, went after a moderate amount of pellets. Interestingly, in most cases where a micropellet was taken into the mouth, the fishes would spit it back out, indicating that they were able to tell that the plastic was not food.

When testing how fishes would react to microfibers, all of the fishes avoided ingesting microfibers regardless of whether food was present or not. This might be because microfibers look very different to typical fish food (i.e. flakes and pellets), or the fishes may just be better able to detect a long, thin fiber as opposed to a rounded pellet. Although the fishes did not mistake the microfibers for food, they did accidently take in the microfibers another way – through respiration (i.e. taking in oxygen to breathe underwater).

When fishes take in oxygen, they open their mouths and opercula (the flap of skin that covers the gills). These areas take in oxygen-containing water and push it over the gills in order to uptake that oxygen into the body. When microfibers were present in the water, fishes would accidently take in the microfibers during normal respiration activities. Oftentimes when a microfiber was inadvertently stuck in the mouths or gills of the fishes, they would cough – releasing the fiber back into the water in a ball of mucous, similar to a wet cough that humans might perform.

Managing Microplastics

While it is clear from this experiment that fishes generally try to avoid eating any microplastic particles, these pesky pollutants will make their way into the fishes internal organs regardless. When their water is filled with microplastics, fishes cannot possibly spit out or cough up every piece that enters their systems. The researchers checked both the gills and the gastrointestinal tracts of these fishes after the study concluded, and found microplastics in all the fishes studied, even the bighead carp, which did not actively try to ingest any plastic particles.

This study contains both good and bad news for fishes. The good news is that although fishes may ingest different amounts of plastic particles depending on their feeding method, all of the fishes were able to identify and expel micropellets and microfibers to some degree by spitting and coughing. These fishes are not just mindlessly eating or breathing – they are able to identify when something has entered their mouth or gills that should not be there. This means that these animals are not consuming nearly as much microplastic as they could be.

The bad news here is obvious – fishes still take up microplastics accidentally, despite their best efforts. As the plastic polluting of our oceans continues, this problem will remain constant, and will likely get worse over time. If fishes continue to contain increasingly large amounts of microplastics, it could have devastating effects on ocean ecosystems, as well as humans. To combat this issue, it will be up to individual consumers (like you and me) to make smarter choices when buying products, governments to put more environmentally conscious laws into place, and businesses to begin employing more eco-friendly means of shipping and production. For more information, you can visit the Plastic Pollution Coalition website.

I received my PhD in Biology from Wake Forest University, and I received a BS in Biology from Cornell University. My research focuses on the terrestrial locomotion of fishes. I am particularly interested in how different fishes move differently on land, and how one fish may move differently in different environments. While I tend to study small amphibious fishes, I’ve had a lifelong fascination with all ocean animals, and sharks in particular. When not doing science, I enjoy running, attempting to bake and cook, and reading.