Pimiento, C., Ehret, D. J., MacFadden, B. J., & Hubbell, G. (2010). Ancient nursery area for the extinct giant shark Megalodon from the Miocene of Panama. PLoS one, 5(5), e10552.

Preface

In honor of the release of “The Meg” movie recently, I wanted to do a special blog post on the star of the movie; Otodus megalodon aka “Megs”. Let me begin by firmly stating that Megalodon or Megs are extinct. Despite Megs being isolated to the fossil record, they have captured the imaginations of children and adults alike. The evidence we have been able to gather from the fossil record has provided a lot of knowledge about how this species may have lived. One of the more fascinating aspects of Meg ecology is the use of nursery habitats by baby Megs. I hope you enjoy this special movie-themed post on an ancient nursery area for this giant shark.

Background

A number of modern shark species including great hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna makorran) and great white sharks (Carcharadon carcharias) use nursery habitats when they are young. A shark nursery is defined as a habitat that provides abundant food resources and, more importantly, protection from predators for baby or juvenile sharks. There are many ongoing studies on the use of nursery habitats by modern shark species but there is little information on the use of nursery habitats by extinct shark species.

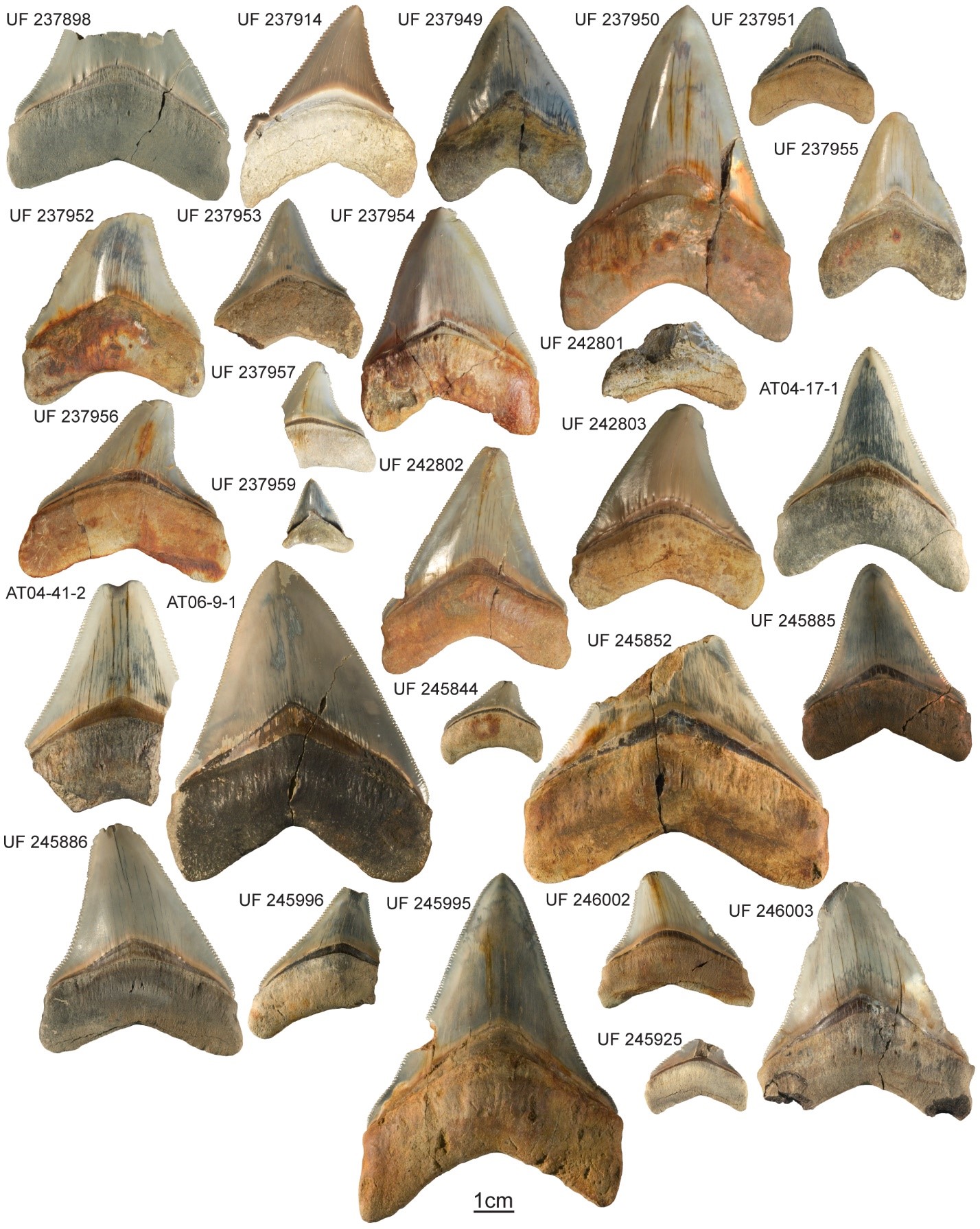

Our knowledge of extinct shark species is the result of studies on fossilized teeth and the rare occurrences of fossilized vertebrae. While guesses can be made about the diets of prehistoric sharks from their tooth structure, it is more difficult to discern life history traits from teeth or vertebrae. However, it becomes easier to answer some questions about the ecology of extinct shark species by also looking at the surrounding rock where fossilized teeth are found. The usefulness of both teeth and geology are exactly what makes the Gatun Formation the perfect place for a study on extinct shark ecology.

The Gatun Formation was part of a marine strait connecting the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea roughly 10 million years ago. Based on evidence from other studies, the Gatun Formation was a shallow water ecosystem with a depth less than 25 meters or 82.5 feet. The ecosystem of the Gatun Formation in the Miocene was very similar to modern marine habitats. The Gatun Formation was also home to a number of shark species including Megs.

Previously two different locations in South Carolina, USA have been proposed as potential paleo-nurseries for the Meg. The high abundance of juvenile Meg teeth and lots of potential prey species have been the main evidence suggesting these sites as shark paleo-nurseries. Interestingly, adult Meg teeth are not commonly recovered from the Gatun Formation in Panama similar to those in South Carolina, USA.

Study Goals

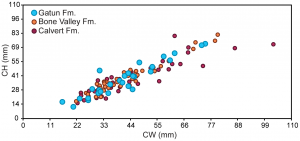

The primary goal of this study was to determine if the Gatun Formation provided a nursery habitat for young Megs. There were several secondary objectives to this study as well; these included comparing tooth sizes with those found in older and newer rock formations to see if the smaller size distribution was limited to Megs from this time period. The authors also estimated the total length of all of the individual Megs to determine maturity of the sharks that hung out in this special area.

Findings

By focusing on these research goals, the authors were able to determine what Meg age group occupied the Gatun Formation. Interestingly, there was no evidence of the small Megs observed in the Gatun Formation indicating an evolutionary trend toward reduced sizes. The Meg teeth observed in the Gatun Formation follow the size trends seen in Megs from older and younger geological deposits. The similar tooth size trends between sites indicates that Megs maintained a relatively stable size range through all geological periods. Establishing that Megs maintained a similar size range throughout the time they were present is important for further comparing the teeth at different locations to see if the Gatun formation is a nursery habitat.

There was also no evidence that the small teeth at the Gatun Formation were the result of the tooth’s position in the jaw. The size of Meg teeth does vary within the Meg jaw; however, all of the teeth examined from the Gatun Formation were similar in size to those from juveniles in other localities. In order to expand on these results, the authors used the tooth size of Megs to estimate total length to determine the life stage of the sharks based on ratios observed in the great white shark. Of the sharks in the Gatun Formation, 21 were juveniles with lengths less than 10.5 meters (34 ft.) while only 7 individuals were adults with an estimated length greater than 10.5 meters. It is not surprising to find adult Meg teeth in a nursery area because reproductive females often give birth in nursery areas and nursery areas do not exclude all large predators that may shed their teeth in this habitat.

Given the high abundance of baby Meg teeth, shallow habitat, and the scarcity of large mammalian prey species it is very likely that the Gatun Formation is representative of a nursery habitat. Furthermore, the other species of vertebrates and invertebrates found in the Gatun Formation indicates a highly productive shark nursery. These environmental characteristics mirror those seen in nurseries used by modern large shark species such as great hammerhead and tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier). This is neat news, as this is the first study to show that sharks have been using nursery habitats as an adaptive strategy for at least 10 million years.