Article: Tarrant AM, McNamara-Bordewick N, Blanco-Bercial L, Miccoli A, Maas AE (2021) Diel metabolic patterns in a migratory oceanic copepod. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 545:151643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2021.151643

The Greatest Animal Migration on Earth

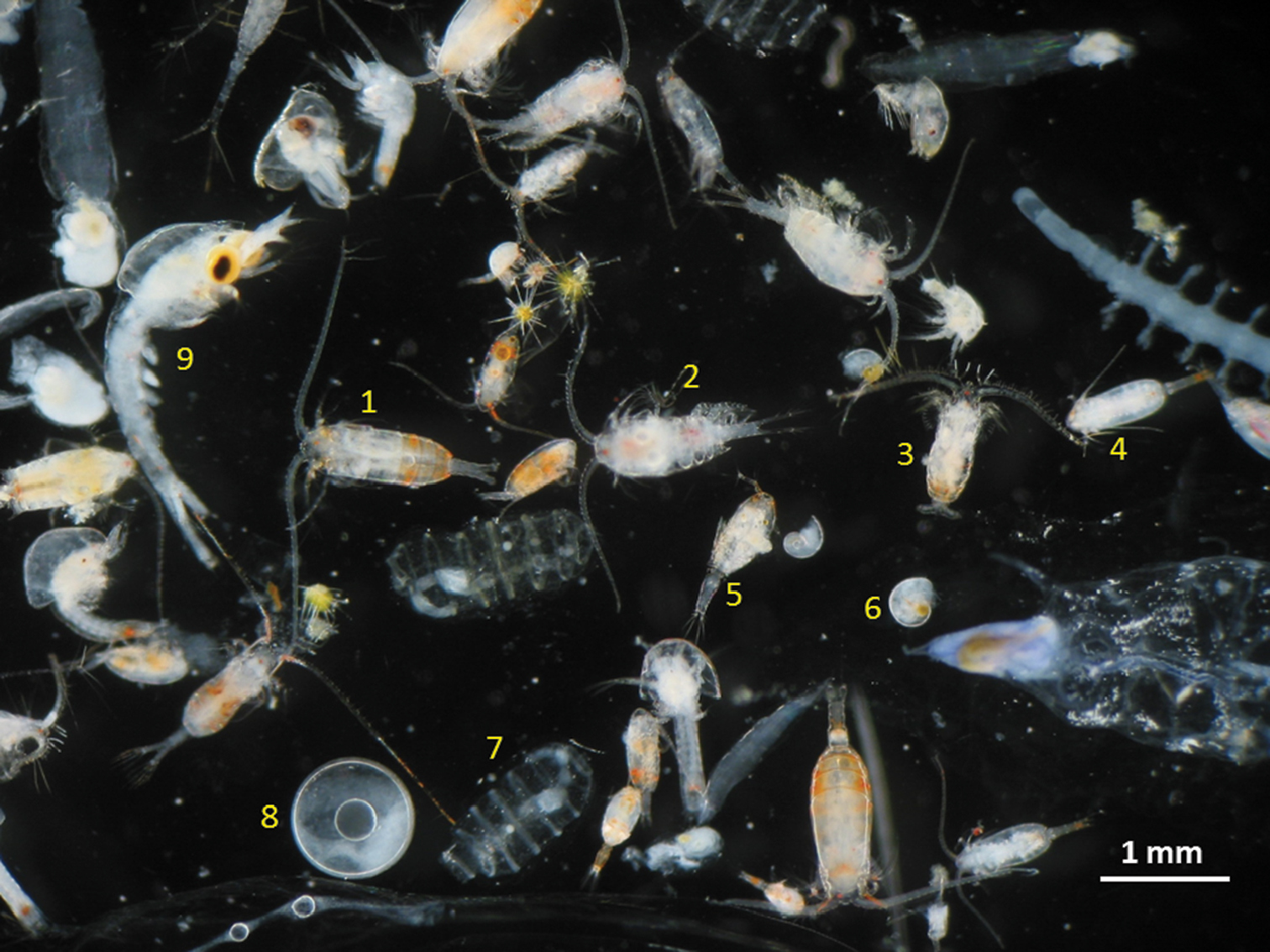

Every day, microscopic animals in the ocean called zooplankton perform the largest migration on Earth. Known as Diel Vertical Migration (DVM), zooplankton rest in the deep waters of the ocean during the day to avoid being eaten by predators and then migrate to the surface waters at night to feed when they cannot be seen. It is estimated that zooplankton migrate about 28 miles per day through this process! Given that zooplankton occur throughout the world’s oceans, it is assumed that numerically, zooplankton perform the largest animal migration on Earth. DVM also has important implications for global climate change because when zooplankton migrate to deep waters, they are transporting carbon to the deep ocean through their defecation and excretion (yes, zooplankton poop and pee!). This process acts as a sink, or removal, of carbon from the atmosphere to the deep ocean, where it can be stored for hundreds of years. Despite the importance of zooplankton DVM, it is still poorly understood how much zooplankton poop, pee, and breathe (e.g., their metabolic rates) when they undergo DVM. It is necessary to measure these metabolic rates to identify how much carbon zooplankton are transporting to deep waters so that we can better quantify this carbon sink.

How do you measure plankton poop?

A group of international scientists recently aimed to quantify these zooplankton metabolic rates during DVM in the Sargasso Sea near Bermuda. Scientists collected subtropical crustacean zooplankton called copepods (think Plankton in Spongebob Squarepants!) and measured their breathing, peeing, pooping at 4- to 7-h intervals throughout DVM. They collected the copepods with a plankton net and then placed them in small glass vials that to measure their breathing with a small fiber-optic probe. They filtered water in the vials that the copepods were swimming in to measure how much the copepods peed. They also counted any fecal pellets (aka poop) that the copepods produced.

The power of plankton to combat climate change

Results from the study found no strong patterns of breathing or peeing from copepods during their DVM cycle. Fecal pellet production was highest during mid-night, which was expected since the copepods were observed feeding for several hours at the surface waters. Importantly, these fecal pellets were also collected in the deeper waters after the copepods had been feeding, which provides direct evidence that zooplankton are actively transporting carbon to the deep ocean in this subtropical region of the global ocean. Finally, given the changes in copepod metabolic rates over a daily cycle, the scientists concluded that copepods adjust their metabolic capacity (e.g., ability to breathe, poop, and pee) in response to variation in environmental conditions and metabolic demands, such as right after a feeding event.

These measurements are important because they can be incorporated into global ocean models aimed at quantifying the amount of carbon transported into the ocean on daily time scales. In addition, they provide high-resolution metabolic rates that better quantify the role of zooplankton in transporting carbon to the deep ocean, which aids in combatting global climate change. Who knew that such tiny organisms moving up and down in the ocean had such a big impact?!

I am a plankton ecologist focused on the effects of rapid climate change on phytoplankton and zooplankton populations and physiology. The major pillars of my research explore how global climate change (1) has and will impact long-term trends in plankton population dynamics and (2) has affected plankton physiology and feeding ecology.

As a Postdoctoral fellow of the Rhode Island Consortium for Coastal Ecology, Assessment, Innovation, and Modeling (RI-CAIM) I am analyzing the multi-decadal long-term plankton time series in Narragansett Bay. By identifying underlying environmental parameters driving plankton community dynamics my work will facilitate efforts to forecast important ecological phenomena in the region.