Let’s Give those Mamas Some Love!

To continue celebrating Mother’s day before May ends, now is the perfect time to look at the amazing bond between humpback whale mothers and their calves. Mother-calf relationships are thought to be the strongest bond in the species, which otherwise usually tends be solitary. Not only are these relationships absolutely indispensable to the calf’s survival, they additionally ensure the calf will eventually integrate into a pod. As a whole, humpback whale populations are rebounding; however, it’s still important to innovate ways to protect this species. Exploring mother-calf pod area utilization might just be the next step in protecting and conserving these giant marine mammals.

Current research in Brazil, Madagascar, Ecuador, and Costa Rica suggests that mother-calf pairs tend to congregate in shallow waters compared to pods without calves. Surprisingly, previous research in Hawaiian Islands Maui, Lana’i, Moloka’i, and Kaho’olawe (otherwise known as the Maui 4-island region) contradict these findings, indicating that mother-calf pods tend to avoid shallower water. Addressing the limitations of previous studies in Hawaii, namely a short observation season, Currie et al. (2018) observe humpback whale pods (both with and without calves) in the Maui 4-island region for a period of 4 years. By understanding mother-calf distribution, we can better protect this species by creating plans to regulate and restrict anthropogenic activity in these very areas and educating guides and tours to avoid pollution while dealing with tourists. Knowledge of where these whale pods are during what season is crucial in making sure the humpback whale remains a species of least concern.

…And just how do you Observe Whales for 4 years?

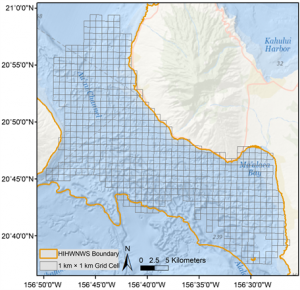

Currie et al. (2018) strategically pick the Maui 4-island Region because of its varied water depth (between 1-270 meters), its location within the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary, and its presence as a major breeding habitat for the species in the Central North Pacific population. All sampled 654 km2 of water was divided into 1km x 1km grid cells, and whale sighting data was collected through a series of daily whale watching trips. These trips departed from a northern and southern harbor and lasted 2 hours. Data on vessels was collected by two trained observers who used their eyes and binoculars to denote visual cues of humpback whale presence. Final data included only a single whale watching trip from both harbors each survey day to eliminate the possibility of analyzing the same pod on the same day multiple times.

Hard Work Pays Off: The result of 4 Years in Data

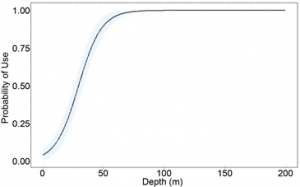

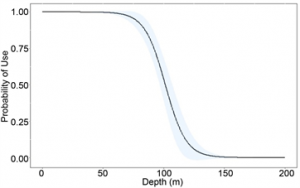

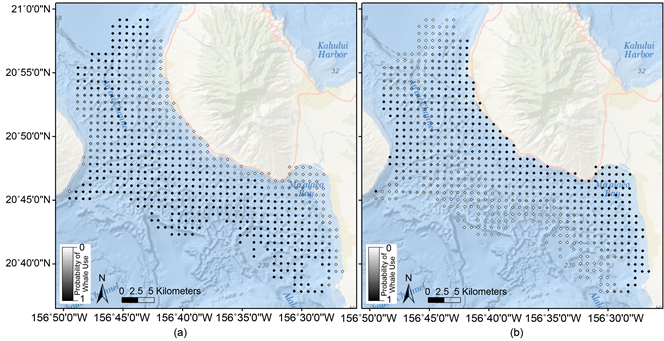

Between December 2013 and April 2017, Currie et al. (2018) completed 1,089 whale watching trips that covered 13,787 nautical miles. Humpback whale pods without calves were detected 786 times in 309 of the grid cells, and whale pods with calves were observed 682 times in 256 of the grid cells. Currie et al. (2018) find that observations of pods without calves was highest in January, with 250 pod sightings, and was highest for pods with calves in March, with 201 pod sightings. Results suggest that water depth was among the most important variables in analyzing humpback whale area use. Water depth was positively related to pods without calves (the deeper the water, the more adult pods were sighted): the highest probability of detecting pods without calves occurred at water depths of 75 meters or more. On the other hand, depth was negatively related to pods with calves (the deeper the water, the less mother-calf pods were sighted). Currie et al. (2018) also note that the area usage between the two types of pods did not overlap—an important finding that further distinguishes where these two types of pods tend to swim.

The study at hand supports previous research asserting humpback whale distribution and area usage patterns depending on age. Not only did mother-calf pods tend to use shallow, nearshore waters, but adult pods were mostly found using deeper, offshore waters. Additionally, results indicate that pods with calves were more likely to use waters south of the sampled survey area. Currie et al. (2018) posit that this usage could correlate with the fact that the sampled southern region is the most protected from strong, rough weather (such as wind swelling) and anthropogenic activities (like commercial shipping traffic). Such protection would give the mother-calf pod greater safety as compared to the northern portion of survey area, which is comprised of larger channels often occupied by shipping vessels and other motor traffic.

Another incredibly important finding is exactly when these pods utilize both types of water. The two types of pods differ in area usage, but results also suggest that mother-calf pods are the last group to migrate. Adult pods were mostly spotted in December and January, while pods with calves were seen between February and April.

An initiative that Shouldn’t End

While humpback whale populations are on the rise, we need to make sure they continue to rise by understanding the species and working on ways to protect it. Knowing exactly where these whales typically are as well as generally when they use certain spaces allows us to determine if their area usage intersects human activities that could be severe stressors. The fact that mother-calf pods tend to use more shallow, nearshore water provides us with the opportunity to regulate anthropogenic activities like recreational or commercial fishing, ecotourism, and marine vessel traffic which can all very much endanger these marine mammals. Currie et al. (2018) specifically suggest creating and implementing a minimum approach distance by water and air, restricting certain types of high speed vehicles (like jet skis), and restricting speed in the areas and during the seasons when mother-calf pods are present. Such knowledge is indispensable in developing relevant conservation initiatives and management plans focused on reducing any disturbances mother-calf pods can face. By continuing to study humpback whales, we can proactively work to preserve their population and ensure their continued path to recovery.

Rishya is a multimedia science communicator with an MS in Media Advocacy from Northeastern University, specializing in Environmental Science Communications and Policy. She spent a year in informal education and policy advocacy at the New England Aquarium as an Educator and at Save the Harbor/Save the Bay as their Communications and Public Relations Coordinator. She also interned for PBS science series, NOVA and was awarded a 2019 Rapport Public Policy Fellowship, which she served at the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries. Rishya’s areas of focus are environmental science, marine science, climate change…and video games!

This seemed to be an interesting one! A lot of blogs that come across arent filled in with great insights, but definetly, this stole the show.