My first exposure to toothed whales was watching the movie Free Willy. Each time the film began and the theme music swelled, my six-year-old heart would explode with feelings of connection and longing for the sea, the way the heart of an intelligent, spunky killer whale might.

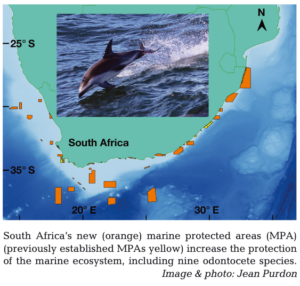

While movies like Blackfish have brought a more critical eye to keeping killer whales in captivity, it is important to remember that killer whales and other toothed whales might need more than the freedom of the sea to keep their populations thriving. Stress placed on them by boat noises and boat strikes, among other threats, can make the sea less than idyll. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are often put into place to protect biodiversity and essential fish stocks, thus aiding the economy, but toothed whales are rarely considered when deciding where to put an MPA. As South Africa looks to expand its protected areas, Jean Purdon and her colleagues set out to learn where the toothed whales are living off the South African coast.

MPAs and South Africa

South Africa is part of the Convention on Biological Diversity, which recently set a target to encourage each of its members to designate a total of 10% of their Exclusive Economic Zones (the marine area controlled by each state) to marine protected areas. In 2016, the country proposed a number of new MPAs that would increase their coverage from 0.4% to 5%. However, The Walker Bay Whale Sanctuary is the only one of the sixty established MPAs chosen keeping the protection of whales in mind. Still, whales cover a lot of ground and have a wide range of habitat preferences, so Purdon et al. decided to run some models to see how much of the whale habitat was already protected and to see where future MPAs would be most effective.

A whale of a model

The researchers modeled the distribution of nine species of toothed whales, from the iconic killer whale to the endangered Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin and the beloved common dolphin. With each species, they looked at a number of environmental factors to determine which were most important in predicting where the animals would be and compared them to sightings of the whales. These included water temperature, chlorophyll a (how much phytoplankton is in the water), salinity, the shape of the sea floor (bathymetry), the distance from shore, the slope of the sea floor, and how quickly the water was moving. Primarily, these factors described how likely it was the dolphins would find food. They gathered all this data together from a variety of sources, but most of their data (54%) about the presence of the whales was from citizen science records reported by non-scientists.

The models showed that each species preferred different characteristics in the water. Killer whales and Risso’s dolphins, for example, preferred to be a certain distance from shore. Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins and Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins chose areas based on the shape of the sea floor (which could be a signifier of the kinds of food they look for), and water temperature was most important for Southern bottlenose whales, dusky dolphins, and Heaviside’s dolphins.

Given that each whale species prefers different kinds of habitats, it is not surprising that MPAs protect some whales better than others. The Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins and Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins had a large percentage of their habitat protected by the MPAs. In contrast, very little of the habitat for Risso’s dolphins, killer whales, dusky dolphins, or the southern bottlenose whales was protected. However, the proposed new MPAs do help protect some more of these animals’ essential habitat.

Why do they go where they go?

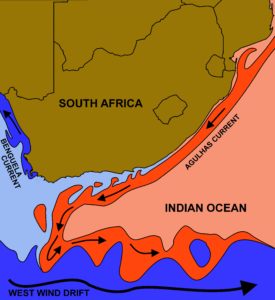

There are a couple reasons these whales may prefer certain parts of the coast. Mostly, it comes down to food. The preferred habitat for killer whales, for example, is an area where the Agulhas currents sweeps warm water over a steep seafloor, moving water quickly and distributing essential nutrients for the production of food. In effect, it’s a great place for cephalopods (animals like octopus or squid), which are great prey for whales.

The Agulhas Bank is another area preferred by whales, where two currents meet, the warm Agulhas and the cold Benguela current. When they meet up, the cold and warm water don’t mix very well at first, creating eddies (you can picture these are curly overlaps) between the two bodies of water, stirring up nutrients from the bottom and once again supporting prey species. Protecting areas like this not only shelters a number of whale species, but all the other species that flock to these productive places to catch a meal. It’s a win-win.

What’s the catch

While most of the models matched the scientific literature on where these animals live, certain species were hard to predict or contradicted the literature. The models had a hard time predicting where Indo-Pacific bottlenose and humpback dolphins would be, describing a much larger range than previous research on the species suggested. In some cases, it could be because the species are fairly flexible and aren’t as limited by the habitat factors in the models. It could also be that some of these species, notably the dusky dolphin, are rarely spotted or that individuals could break away from the other dolphins (become vagrants) and swim into areas they wouldn’t usually go but would be closer to people. Additionally, records for these whales were notably higher by larger cities. This makes sense given the data came from citizen scientists. With more human eyes on the water, it is more likely the whales will be seen. All told, these models are a good start, but do leave some space for improvement in the future.

Mostly, however, the study shows that the majority of the whale species are poorly protected, with most species having less than 5% of their habitat protected by the MPAs. Those best protected only reached about 14%. In the future, choosing MPAs with whales in mind could go a long way towards protecting whale species, even if Willy is already free.

I am a PhD student studying Biological Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography. My interests are in food webs, ecology, and the interaction of humans and the ocean, whether that is in the form of fishing, pollution, climate change, or simply how we view the ocean. I am currently researching the decline of cancer crabs and lobsters in the Narragansett Bay.