Global sea level is projected to rise at a rate of 3.7mm/year throughout the first half of the next century, according to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPPC). As coastal communities around the world brace to meet this worrying projection, it’s become clear that many simply have no options left, as was recently discussed by planning authorities in the Florida keys, while others will need to implement lasting changes in land use and development practices.

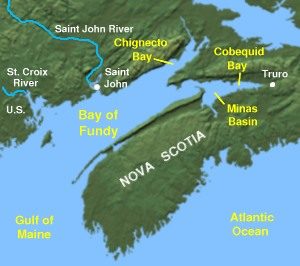

In Nova Scotia, where 50% of coastal salt marshes (and up to 80% along the Bay of Fundy) have been lost to historical dyking, there are few natural buffers left to protect many coastal settlements. The Genuine Progress Index for Atlantic Canada estimates the continued loss of wetlands to development in this province to equal about $2 billion every year in lost wetland services, such as water purification, groundwater recharge, and erosion mitigation. In an area where sea level is expected to rise at least 1m in the next century, this lack of natural protection puts many Nova Scotians at risk of eroding shorelines, flood damage to homes and wharves, contaminated drinking water, and rising road maintenance costs. Dyke breaching has proven to be an effective way to restore many of the benefits salt marshes convey to coastal communities, most seeing plant regeneration and the restoration of ecosystem services within just a few years. Yet, coastal population density and private/provincial investments in promoting such development are increasing in Nova Scotia (and in many other areas of the world). In fact, despite the existence of provincial legislation designed to protect wetlands, it is still possible in Nova Scotia to purchase and destroy wetlands with little consequence.

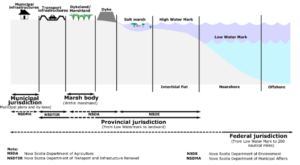

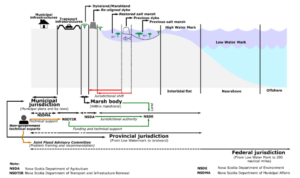

In most Canadian provinces, the Queen owns everything up to the high water mark, making most of any given wetland technically “crown land”. Most provinces also have policy prohibiting net loss of wetlands, whether they be on crown or private land. However, wetlands that haven’t been formally surveyed, that aren’t included in the provincial wetland database, or that are seasonally dry are frequently left out of provincial processes that might otherwise protect them. You can buy “land” from the Queen that isn’t even land. Additionally, there’s no legislation preventing development in the terrestrial parcels immediately adjacent to wetlands, even in areas we know will be underwater in 50 years, meaning many remaining salt marshes have little room to recede inland as waters rise.

For the uninformed home-buyer, this lack of protection can prove disastrous the first time they experience a hurricane, quick winter melt, or even just a heavy rain. Still, there are little successes we can learn from. In places where there is public support for restoration projects, where there are champion policy makers or land managers, or where passionate informed landowners are looking to change course, researchers and environmental NGOs are making headways in salt marsh restoration. How do we get scientists, government, and the public to all work together to save these natural coastal defenses?

Researchers Tuihedur Rahman and Kate Sherren from Dalhousie University and Danika van Proosdij from Saint Mary’s University set out to investigate what kinds of institutional changes led to the successful restoration of a coastal salt marsh in Truro Nova Scotia last year, allowing the town to adapt to increasing flood risk.

Truro is a medium sized Nova Scotian town housing ~12,000 residents and located within the floodplain of the Salmon River, which feeds the Bay of Fundy. Much of the area has been dyked for agricultural use, though most dykes now protect residential and commercial developments as well as transportation infrastructure from the river’s seasonal flooding. A decline in agricultural industries has resulted in much of the former farmland being left fallow, if not sold for residential and commercial development. Because of its location, both adjacent to the Salmon River and experiencing the extreme tides and icejams common along the Bay of Fundy, Truro has suffered from nearly seasonal flooding for years. The town was the subject of several flood studies occurring between the 1970s and early 2000s, with most suggesting the continued use of hard infrastructure like dykes and seawalls as the only solution for controlling flood risk. Some even suggested adopting expensive projects like raising the dykes, creating ice control berms, and even a tidal dam that would cordon off the Bay of Fundy.

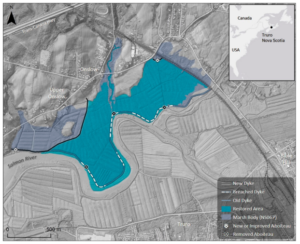

Due to the exorbitant cost of the proposed projects combined with uncertainty in the technological ability to achieve such high aims, the town and county decided to seek out a more sustainable and cost-effective solution. Ultimately, the community decided that flood risk might be reduced in part by restoring the Onslow Salt Marsh, a dyked tidal wetland on the north side of the town.

Wetland restoration projects do not come without a cost, though, and wetlands and associated lands in Nova Scotia are managed by a number of different municipal, provincial, and federal authorities. Rahman et. al. suggest that five key lessons can be learned from the success of the Onslow Salt Marsh restoration project, which brought together many different players to implement an innovative nature-based solution:

Players Need to Understand the Issue

- Until Tropical Storm Leslie hit Truro in 2012, all flood risk management activities done at the municipal level were based on hard infrastructure solutions and a few soft legal changes like restricting certain kinds of development in the floodplain. When the storm broke through a privately-owned dyke and flooded a number of homes and businesses, it became apparent that the affected citizens and their local politicians didn’t know why the dykes were originally created (for agricultural use) and they demanded the municipality and province work together to repair the dyke system they thought was designed to protect them. This prompted an in-depth risk assessment study and floodplain mapping project that both projected flood risk into a future under climate change and compared traditional hard infrastructure mitigation methods with less costly and more long-term effective options like wetland restoration. The use of advanced scientific tools and methods gave the end recommendation a kind of legitimacy while the intentional interpretation of the science in non-technical language allowed all the parties involved to develop a common understanding of the issue and commitment to its solution.

Use the Bureaucracy to Your Advantage

- Wetland management as a jurisdiction is shared by many different departments within different levels of government in Nova Scotia. The provincial Department of Agriculture is responsible for maintaining existing dykes and their Minister can decide whether to develop, maintain, or improve a dyke system. The provincial Department of Lands and Forestry is responsible for crown lands, beaches, and most public trails, many of which are associated with dyke systems. The Department of Culture and Heritage is responsible for archeological sites and designated special places, which also includes dykes, which are remnants of Acadian culture in Nova Scotia. The Department of Environment is responsible for wetlands and develops climate change mitigation strategies. And that’s just the provincial jurisdiction. The municipality is also responsible for some aspects of land use management. And then there are organizations called Marsh Bodies, which are collections of marshland owners who may act as a governing body on a small scale. Avoiding a lasting jurisdictional nightmare, the Truro project prompted the Department of Agriculture to give up their responsibility for maintaining dykelands, which they were finding to be increasingly expensive. The provincial Department of Transportation and Infrastructure, while not having any management responsibility over dykelands, is responsible for restoring marshes in response to building roads in others, and they found the new idea of salt marsh restoration a good way to access priority compensation projects. Together, each of the organizational players were able to see potential advantages to making small changes within their existing institutional practices.

Distribute Roles and Responsibilities Strategically

- The Truro project was a success partly because the different provincial and municipal players were able to exchange resources and responsibilities to get the project done. The Department of Transportation and Infrastructure gave up funding for land purchases and operational expenses, while Department of Agriculture staff were essential go-betweens for the private landowners, scientists, and provincial government staff. The Department of Environment, which adopted the on-going management and conservation of the salt marsh, also acted as a bridging agent between all departments so they could get together and work through a single decision-making platform.

Decision-Making Autonomy Helps Avoid Red Tape

- In a system where land management responsibilities are shared between many equal players in a complex network of decision-making abilities, having some players with a certain amount of autonomy is key to achieving effective collaboration. In Truro, the Departments of Transportation and Infrastructure and Agriculture were able to negotiate and adapt their respective roles and resources in order to work more effectively with each other. Without this social license to diverge from normal practice, the project might not have gone ahead.

Meet Frequently and Informally

- The Department of Environment provided a number of informal opportunities for all the different players to get together, hear the science, and build a shared trust of each other and commitment to the flooding problem. Gathering regularly was especially important for the Marsh Bodies, who were concerned about being heard and appreciated the opportunity to gain new scientific understanding of the issue.

The Onslow Salt Marsh restoration should act as an example of effective institutional collaboration for climate change adaptation, in Canada and around the world. Bringing scientists, government, and public representatives together in an informal setting on a regular basis was key to achieving the more cost effective and sustainable solution of dykeland naturalization in the flood-prone town of Truro. The researchers suggest that adopting flexible coastal adaptation strategies allows different players to innovate and change their behaviours, fostering a more productive environment and achieving better outcomes than by implementing rigid department-specific policy recommendations. Information, trust, and regular interaction are necessary for achieving the climate change adaptation our coastal communities depend on.

Hi! I’m Rebecca Parker. I’m an ecologist and plant lover working in non-profit conservation in Nova Scotia Canada. I trained at Dalhousie and Ryerson University, where I completed a Masters in Environmental Science and Management. I like botany, wetlands, and wetland botany! On the sciencey side, I like to write about current topics in population and community ecology, but I’m also really interested in environmental outreach, how exposure to science and demographics affect environmental values and behaviours, and best practices for building community capacity in environmental stewardship. Check out my instagram for photos of the awesome nature I see through my work.