I’ll always remember the first time I touched a small, spotted stingray at the New England Aquarium: soft, slightly bumpy, and slimy – like Vaseline.

As a child, I was always wary of stingrays and their menacing barbs. The real animal turned out to be much less terrifying. After a couple minutes of watching the animals fly seamlessly through the water, rising gently to bump my hand with their noses, I was so enchanted that I didn’t even care when I learned that rays are soft because of a layer of mucous on their skin.

While I now feel more sure-footed around stingrays, the role of stingrays in a changing world is less certain. Sharks, one of stingrays’ top predators, have declined from aggressive fishing. We still don’t really know what the loss of sharks would mean for stingrays, or for the coral reefs where they both live. Scientists at James Cook University and the Australian Institute of Marine Science want to find out.

Fun fact – you are what you eat

Stingrays and sharks are part of a group called elasmobranchs, fish whose skeletons are made of cartilage – not bone. Their entire bodies are made up of the same floppy material you can feel in your ears and at the tip of your nose. Since larger sharks eat smaller species of rays, they literally are what they eat.

Taking the bait

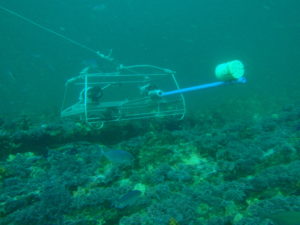

To take a look at how stingrays respond to how many sharks are nearby, the researchers used baited remote underwater video systems (called BRUVS) at 12 different sites, spanning 19 reefs and 6 different countries in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific. Each BRUVS was left out for at least one hour. Since a BRUVS is baited, they used small fish like pilchards and slimy mackerel to attract stingrays to the camera.

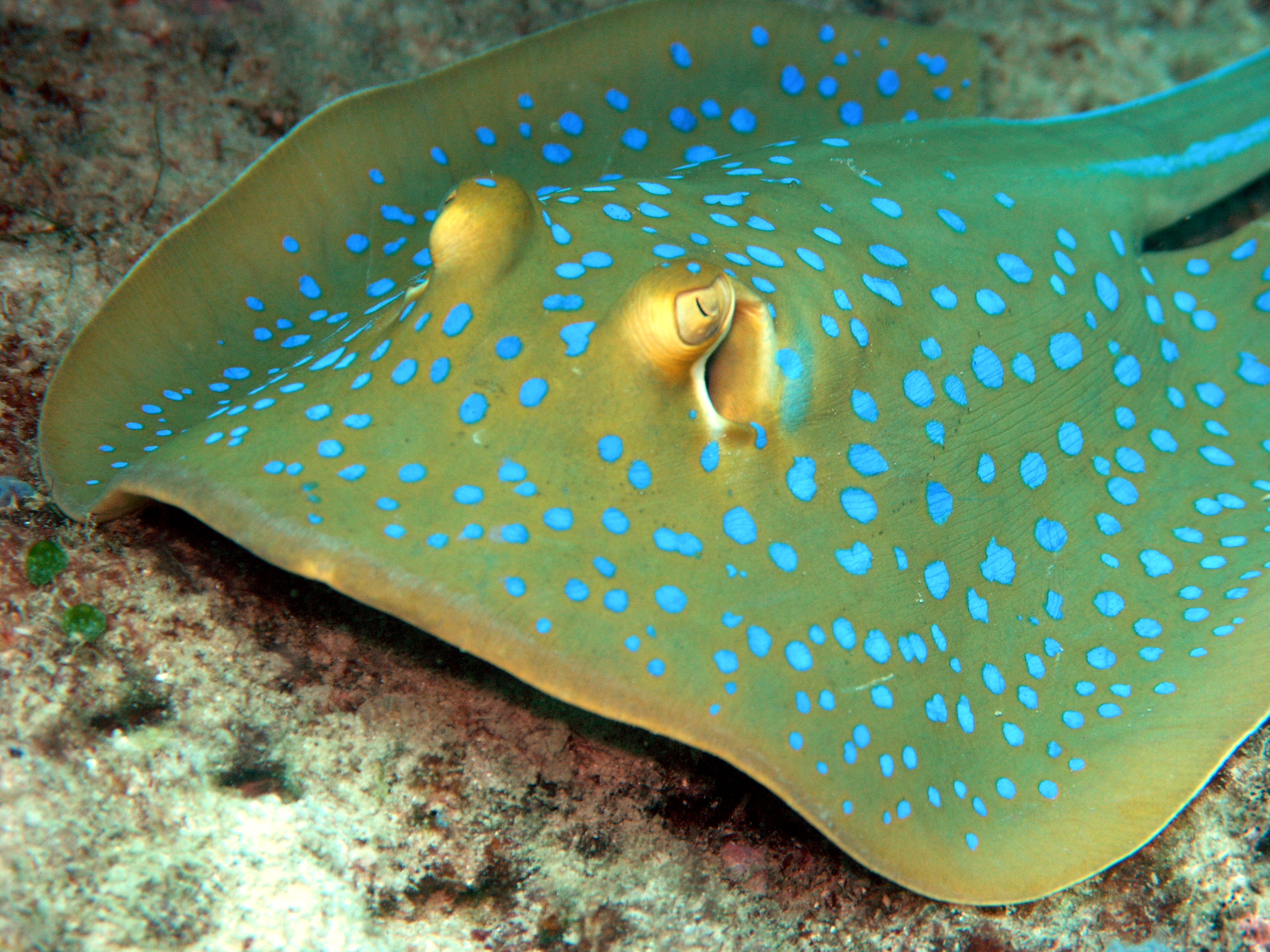

While there are hundreds of kinds of stingrays, Dr. Samantha Sherman and her colleagues decided to focus on two genera, Neotrygon (or bluespotted maskrays) and Taeniura (fantail rays). These rays are small, generally serve as prey to various predators, and are fairly abundant in the researchers’ study sites. The researchers also recorded all species of predators they saw in the footage.

Additionally, they categorized rays as either “transient,” meaning just passing through, or “resident,” or those that came close to the BRUVS and meandered a bit in frame. They also noted if the rays stopped to eat the bait.

Scaredy rays

The scientists found that three different kinds of sharks comprised 85% of all the predators they spotted: grey reef, blacktip reef, and whitetip reef sharks. They also found that the more sharks that were in an area, the fewer rays they tended to see. However, the number of fantail rays tended to drop more quickly the more sharks were around compared to the bluespotted maskrayas. Either the fantail rays were more afraid of sharks, and thus hid more, or fewer of them survived in the presence of sharks than the bluespotted maskrays. The number of rays was also impacted by how deep the sites were, with deeper areas having fewer rays, and how structurally complex the site was, with more rays spotted in flatter sites.

Rays also responded to how many predators were in an area. Overall, about half of the rays recorded were classified as “residents.” However, the more predators there were, the less time resident rays spent checking out the bait and the fewer rays actually took the bait.

What this means

In short, when there were more predators, the researchers saw fewer rays, and those rays spent less time out and about. While this may seem pretty straight forward, this change in ray behavior actually has several important implications.

A marine reserve, or an area of the ocean protected from fishing and development, is often considered successful if it manages to support a higher number of sharks. That’s because sharks are apex predators, meaning the availability of their food relies on entire food chains surviving. If any branch of the ecosystem isn’t working well, then it may not be able to sustain sharks. However these results suggest that determining if a marine reserve is good for rays is tricky because if there are lots of sharks, the rays may hide more. Divers and scientists can’t get an accurate count if they are measuring rays by sight alone. In the future, scientists must consider how animal behavior is impacted by the presence of other species.

Additionally, while the number of rays seems to increase with fewer predators, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s because fewer rays are eaten. It might have to do with fitness – or rays’ physical condition. Rays generally kick up sand and sediment to find tasty animals below, like clams or crabs. This is very conspicuous and can easily draw the eye of a hungry shark. With fewer sharks, however, rays may be more comfortable hunting for more food, which puts them in better shape to reproduce and make more rays. This isn’t a complete reprieve from predators, since humans fish for rays at a higher rate in Southeast Asia than anywhere else in the world. Since rays still seem abundant, it may be that they’re simply very productive, especially in areas where they don’t have to worry about sharks.

Finally, this means that rays could have a large impact on their prey if sharks continue to decline. Without fear of being eaten and with higher numbers, rays could shape ecosystems through what they eat. What Sherman and her colleagues suggest was that the presence or absence of sharks in a reef could change reefs just by changing stingray behavior. Ultimately more research is needed to see what the large-scale impacts could be, but for the time being, we know that “when sharks are away, rays will play.”

I am a PhD student studying Biological Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography. My interests are in food webs, ecology, and the interaction of humans and the ocean, whether that is in the form of fishing, pollution, climate change, or simply how we view the ocean. I am currently researching the decline of cancer crabs and lobsters in the Narragansett Bay.