Citation: Barth-Jensen, C., Daase, M., Ormańczyk, M. R., Varpe, Ø., Kwaśniewski, S., & Svensen, C. (2022). High abundances of small copepods early developmental stages and nauplii strengthen the perception of a non-dormant Arctic winter. Polar Biology, 1-16. DOI: 10.1007/s00300-022-03025-4

Polar ecosystems experience extreme seasonal variations in light and temperature. North of the Arctic Circle, the sun stays above the horizon for weeks during the summer—and during the winter, it may never rise! The darkest months of the year pose challenges to the organisms that live there. Reduced light levels limit the growth of phytoplankton—algae that use photosynthesis to gain energy from the sun, like plants. Phytoplankton are food for small animals that live in the water column, called zooplankton, and zooplankton are in turn a major food source for larger animals like fish, seals, and whales. Because the Arctic winter is a period of low food availability, scientists have traditionally thought that polar organisms are relatively inactive during this time, with zooplankton attempting to conserve energy while they overwinter, or wait for spring. However, new studies show that many zooplankton are surprisingly active, and can even reproduce, during the winter.

In a study recently published in Polar Biology, a team of researchers studied populations of zooplankton during the Arctic winter. They focused on small crustaceans called copepods—an important group of zooplankton that may in fact be the most abundant animals on the planet. Surprisingly, the winter waters were teeming with baby zooplankton, showing that these animals were actively reproducing and growing during the polar night.

Going fishing… sort of

The researchers collected zooplankton during the polar night in January 2017, in waters near Svalbard, Norway. This archipelago lies halfway between Northern Europe and the North Pole, and is home to the northernmost permanent settlement on Earth. The process of collecting zooplankton boils down to putting a big net in the water and dragging it behind a boat—which is hard to do in the winter in such a remote location! Because of this, we know much less about the Arctic Ocean during the winter than during the summer. After enduring some rough weather, the scientists obtained their samples and began the arduous process of counting and identifying individual animals by hand.

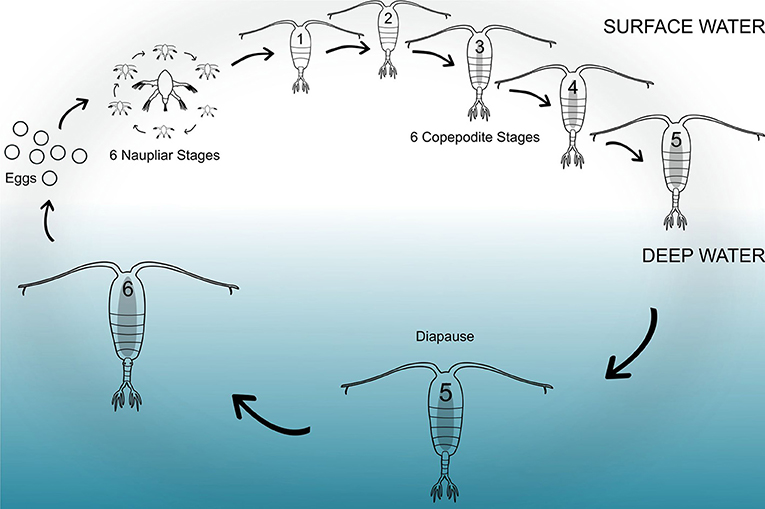

Copepods progress through a series of molts as they grow, from early larval stages to juveniles, and finally to full adults. The researchers counted the number of individuals from each species and developmental stage, gaining insight into where animals were in their life cycle when they were collected. For example, the presence of young copepods means that these animals were born in late fall or early winter, whereas older juveniles would have been born the previous spring.

Many different ways to survive the winter

The researchers identified three different strategies for overwintering. The largest species of copepods (Calanus spp.) spent winter as late-stage juveniles. These species represent the traditional strategy of seasonal dormancy: they reproduce in the spring, store lipids throughout the year, and use those fat reserves to survive the winter in a dormant state. The second strategy was practiced by one species, Microsetella norvegica, which overwintered as adults and did not actively reproduce during winter. M. norvegica is too small to accumulate much fat, but it might survive the winter by feeding on detrital particles. Finally, the populations of the remaining copepod species contained every life stage, from larvae to adults. In fact, the populations of Microcalanus spp. were dominated by the youngest juvenile stages, meaning that winter is an important reproductive period for this type of copepod. Other copepods had more middle-stage juveniles, suggesting that they primarily reproduce in late summer or fall and use the winter as a period for growth and development.

Copepods were the main focus of this paper, but the authors also found the larvae of other animals, like worms and shellfish. These organisms are the meroplankton: animals that spend their larval lives as plankton, free-floating with the ocean’s movement, but eventually settle on the seafloor as adults. Copepods are holoplankton, meaning they spend their entire lives in the plankton. Since the researchers found many meroplankton larvae, it suggests that both meroplankton and holoplankton were reproducing during the winter.

An active Arctic, year-round?

Why would animals reproduce during such a difficult time? Many larvae born in the fall or winter probably starve to death. Low temperatures also slow down development and limit the number of eggs females can produce. However, the winter might actually be a relatively safe time in the lives of Arctic zooplankton. Predators that use sight, such as fish, may be less abundant and have a harder time detecting their planktonic prey during the long weeks of constant darkness.

This study highlights the resiliency and flexibility of marine life, and also challenges our traditional views of polar ecosystems. Different groups of animals use different strategies to survive and thrive during the winter months. Rather than thinking of the polar night as a period of universal dormancy, we now know that many animals can use this time to actively grow and reproduce. Although sampling is difficult during the winter, it is important for oceanographers to collect more data to gain a better of understanding of how polar ecosystems operate in winter, and how they will be affected by climate change.

I am a PhD student at MIT and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, where I study the evolution and physiology of marine invertebrates. I usually work with zooplankton and sea anemones, and I am especially interested in circadian rhythms of these animals. Outside work, I love to play trumpet, listen to music, and watch hockey.