See article here: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10530-017-1517-y

Tunicates are underappreciated seafloor animals. Living sedentary lives and resembling some kind of marine slime, they don’t usually make it into headlines or flashy ocean documentaries. They are, however, important components of marine ecosystems (super cute ones too, like these bright blue ones), building bottom habitats and providing food for a number of fish and other marine animals. As adults, many tunicates are glued to the seabottom, filter feeding on passing plankton and doing their best not to breed with their siblings. Larvae, though, are free swimming and more closely resemble tadpoles than adult tunicates. Released larvae swim for a couple of hours to days until they settle down somewhere new and form their own colony.

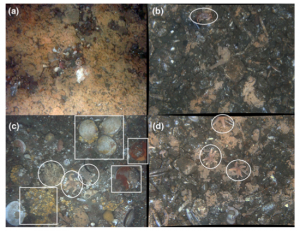

Didemnum vexillum is a type of tunicate scientists think is native to the Pacific Ocean off Japan. Since the mid 1900s, it’s been making its way into the east and west Atlantic, North Sea, and Mediterranean, supposedly transported by imported oyster stock for aquaculture operations. Commonly known as carpet sea squirts, carpet tunicate, or, my personal favorite, Marine Vomit, Didemnum has slowly made itself a pest to benthic ecosystems throughout the world. Growing at depths of 200 or so feet, Didemnum forms coral-like colonies of relatively small but connected individuals that collaboratively envelop entire rocks, coral formations, shellfish beds, and other hard surfaces. If smothering wasn’t enough, Didemnum also secretes a toxic substance over its substrate to prevent predation and the settlement of other larval species. It is The Blob, only underwater and lacking it’s own blockbuster.

Invasive species are a hot topic in ecology and evolution. Most scientists define invasive species as non-natives (or aliens) that have become a problem in their newly colonized homes. They may be really good at eating native species, competing with natives for space, or otherwise excluding natives from their habitats. Sometimes, aliens get blamed for the degradation of native species that are actually failing in response to other changes, almost always rooted in human interference (pollution, habitat degradation, fragmentation, etc.) Though, if Donald Trump tried to implement an invasive species travel ban it would probably be widely endorsed by the scientific community for the much needed research funding it would open up. But I digress… On short time scales, those important to us humans, the introduction of a new species can seriously alter the normal functioning of an ecosystem we depend on. The number of “invaders” has also dramatically increased in the last 50 years. Where humans have benefited from increased international trade and complex world transport systems, so have alien species. It is therefore important to understand when and why they become invasive; whether an alien is causing ecosystem change or if they’re just moving into available territory.

Scientists are concerned about Didemnum because, where it’s found, many other previously abundant species tend to disappear. From the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, Didemnum arrival seems to exclude a variety of seafloor organisms. Kaplan et al. asked whether the seemingly unstoppable Didemnum is the driver of the ecosystem change noted widely across its invasion track, or if it’s just an opportunistic squatter taking advantage of space opened up by other human activities. It’s an important question, because the answer could give scientists clues to the best course of restoring these ecosystems.

They took a vessel-towed underwater camera called a HabCam to the bottom of Georges Bank to investigate the causes of bottom system decline there. Georges Bank has a long history of bottom trawling, a destructive fishing method that scrapes the ocean bottom of most coral and other habitat-forming species. It’s also the site of a number of protected areas where bottom trawling is no longer allowed. This makes it the perfect spot to compare Didemnum colonies and see what’s causing decline in bottom communities: Trawling or Didemnum.

Kaplan et al.’s underwater camera found a variety of native sea sponges, sea stars, cnidarians, polychaete worms, various shellfish, and Didemnum in both the open and protected areas on Georges Bank. Didemnum presence, especially in large colonies, was correlated with decreased biodiversity of other bottom species. Interestingly, this decline did not differ between the open fishing area and the protected area under study. Species composition differs between protected areas and those open to fishing, as a direct result of bottom trawling, but both areas decline in biodiversity when Didemnum is present. This supports the hypothesis that the invasive Didenum tunicate drives ecosystem change, and isn’t just riding on the back of another destructive human activity. Builder, it is!

Kaplan et al.’s study is important for informing the builder vs. squatter debate in invasive species biology, but also because it profiled a section of a highly altered bottom site on Georges Bank, one of the most important fishing areas in the world. Future studies in seafloor community dynamics could benefit from the success of this study’s use of the towed underwater camera to collect abundance data. Follow up studies on the role played by Didemnum in seafloor communities could look at larger study areas, multiple protected areas, and regions more intensely fished. It will be important to repeat Kaplan et al.’s approach to monitor changes in the Didemnum-macroinvertebrate relationship over time. Even though Didemnum may have arrived on Georges Bank as long as 50 years ago, community ecology works on spans of hundreds of years, and continued monitoring for Didemnum (as well as other newcomers) will be important to inform future seafloor management.

Hi! I’m Rebecca Parker. I’m an ecologist and plant lover working in non-profit conservation in Nova Scotia Canada. I trained at Dalhousie and Ryerson University, where I completed a Masters in Environmental Science and Management. I like botany, wetlands, and wetland botany! On the sciencey side, I like to write about current topics in population and community ecology, but I’m also really interested in environmental outreach, how exposure to science and demographics affect environmental values and behaviours, and best practices for building community capacity in environmental stewardship. Check out my instagram for photos of the awesome nature I see through my work.