This article is part of a collaboration between Sharkbites Saturday and the Shark Research & Conservation Program (SRC) at the University of Miami. This contribution comes from Mitchell Rider, a master’s student and the acoustic telemetry database coordinator for SRC.

Article: Ryan, L. A., Chapuis, L., Hemmi, J. M., Collin, S. P., McCauley, R. D., Yopak, K. E., … & Schmidt, C. (2018). Effects of auditory and visual stimuli on shark feeding behaviour: the disco effect. Marine Biology, 165(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-017-3256-0

Introduction

Although efforts to conserve shark populations have increased worldwide, sharks are still perceived as a threat to humans. To help improve interactions between sharks and humans, a variety of shark mitigation methods, or ways to prevent shark attacks, have been developed. Some of these methods are quite harmful (culling and beach netting) and can result in shark deaths, but there are some methods that can be non-harmful. These methods aid in reducing interactions between humans and sharks, and also can be used to deter sharks away from fishing gear to help reduce bycatch. Bycatch occurs when a fishery catches organisms that were not meant to be caught (e.g. a shark is caught by a fishery targeting tuna).

The non-harmful mitigation devices that are currently used stimulate the electrosensory and olfactory systems of the sharks. The electrosensory system consists of the Ampullae of Lorenzini, which are jelly filled pores covering the sharks nose that can detect electrical fields (like ones given off by the heart beats of their prey). The olfactory system is basically the shark’s sense of smell, which allows it to detect drops of blood in the water. Even though these devices can be an effective way to deter sharks from an area, not one mitigation method is useful for all species, so it is important to investigate other potential mitigation methods that can stimulate other sensory systems. In their recently published article, Ryan et al. (2018) tested the responses of different sharks to “the disco effect”: a combination of audio (loud, artificial sounds) and visual (intense strobe lights) stimuli.

The Study

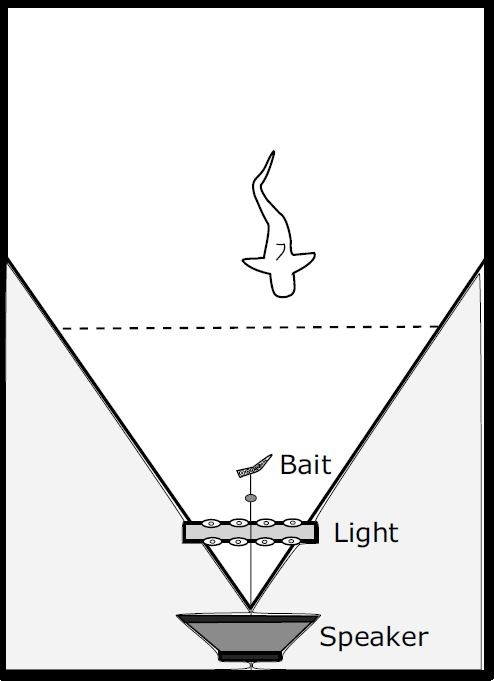

Three different types of sharks (Port Jackson, epaulette, and great white) were exposed to the disco effect. The Port Jackson and epaulette shark were exposed to these stimuli in a laboratory setting while the great white was exposed to these stimuli in the field. The apparatus used in both settings consisted of a speaker, a light, and a piece of bait (as seen below). During the experiment period, each shark was exposed to different sound frequencies and strobe light settings individually and in combination with each other. A shark’s willingness to take the bait was the measure of effectiveness of these stimuli. If the sharks were willing to take the bait during any of these combinations of stimuli, then the disco effect may not have been effective at deterring an individual.

Once the experiment was complete, Ryan et al. (2018) discovered that both the Port Jackson and the epaulette sharks were found to take the bait fewer times when exposed to a combination of light and sound stimuli and light stimuli individually. The white sharks responded a little bit differently. When exposed to just the light, they did not shy away from the bait. However, when the disco effect was implemented, the white sharks spent significantly less time near the bait. Even though a significant difference was discovered, the average amount of time spent near the bait during the disco effect versus the control (no stimuli) only differed by 0.8 seconds.

What does this mean?

This study showed that a combination of light and sound can influence shark behavior to some degree. But, this effect seems to be variable among species. The Port Jackson and epaulette sharks were deterred by the light and sound combination; however the white shark was not. Since this method was not as useful for deterring white sharks, it should not be used as a method of mitigation between humans and sharks. That is not to say this method should not be tested on other species of sharks. It should still be studied on species that the public finds equally “threatening”, such as bull and tiger sharks as the combined sound and visual stimuli may have a different effect. Since the Port Jackson and epaulette sharks are of no concern towards humans, the use of this effect could be used in fisheries that have a high bycatch of similar species of sharks. Exploring ways to implement the disco effect in different types of fishing gear such as bottom trawling or long-lining could mean hope for sharks that are susceptible to being caught as bycatch.

Ryan et al. (2018) investigated shark reactions using a different set of senses that not many researchers have investigated before. This research is a crucial stepping stone in terms of discovering how shark sensory physiology works. Continued research in this field may yield an effective deterrent that works for a lot of shark species; if such a deterrent could be used on fishing gear, this would be a huge boon for shark populations worldwide, as shark populations would benefit from reduced bycatch. In addition, these potential deterrents may also help reduce the amount of human and shark interactions, thus protecting humans and sharks from one another.

Happy Shark Week from everyone here at oceanbites and Sharkbites Saturday!

I am currently a PhD student studying marine science at the University of Massachusetts Boston, with my research based at the New England Aquarium. My research interests center around conservation physiology of fishes, particularly sharks, in relation to climate change. I have a passion for scientific outreach and communication with my biggest triumph being my participation in an hour long science-based episode of Shark Week 2016 entitled Tiger Beach. In my spare time I like getting outside hiking, rock climbing, diving, and practicing my yoga headstands.