Journal source:

Imagine: what if you could still find unimpacted marine ecosystems? There are very few places left on earth that have escaped adverse impacts from human activities, and this may also be true for our oceans. While overfishing, pollution, invasive species, climate change, and habitat destruction have left much of our marine habitats in a fragile state, there is some good news. Far away from the coasts, remote islands are largely unimpacted by human activities and may provide one of the last opportunities to study the biodiversity of marine species.

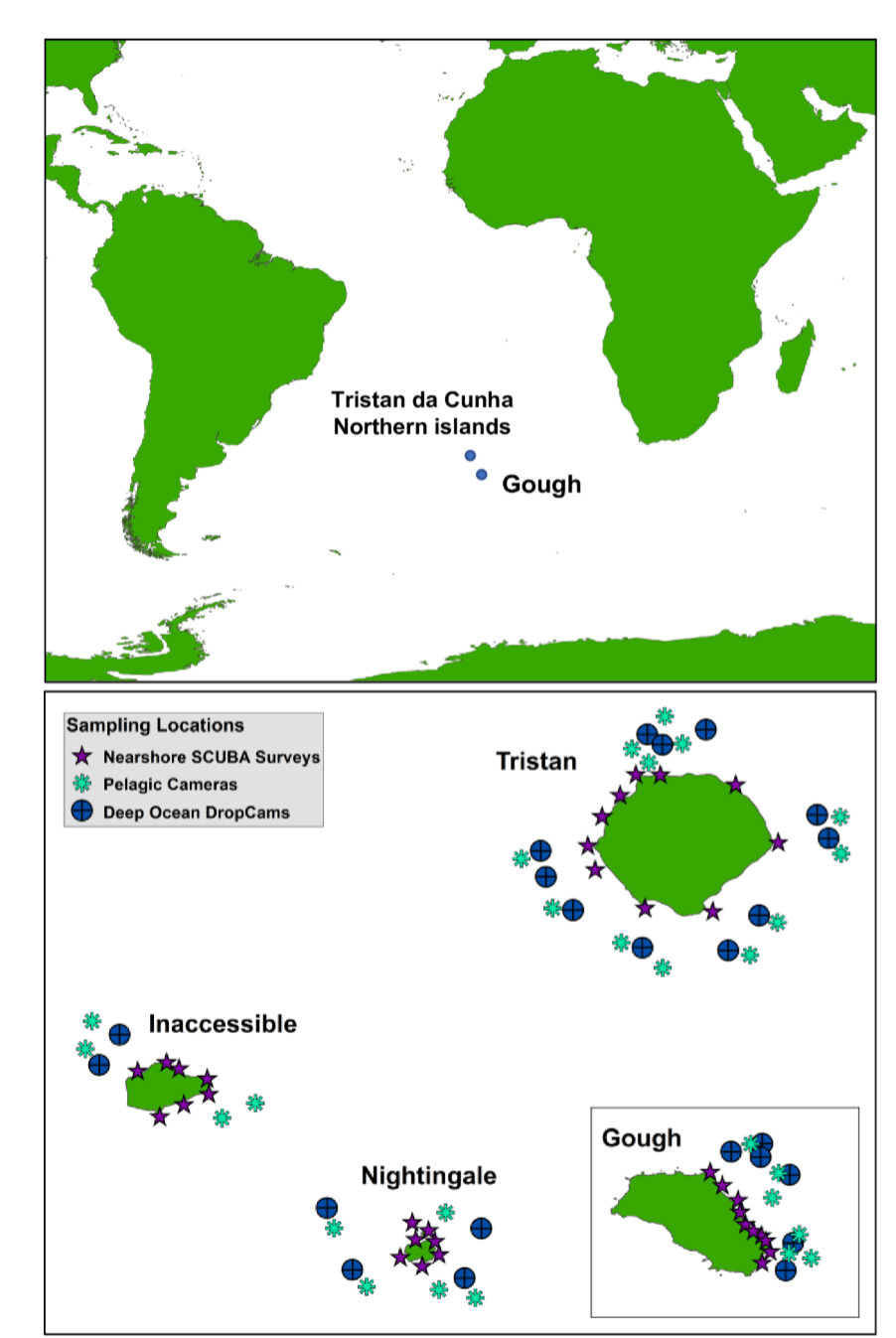

One relatively pristine marine system can be found in Tristan da Cunha Islands, an archipelago of 4 rocky volcanic islands located in the South Atlantic Ocean, and part of the United Kingdom Overseas Territories. The main island of Tristan da Cunha has been inhabited by at least 300 people since the late 1800s, while the islands of Inaccessible, Nightingale, and Gough have remained uninhabited throughout much of their history.

While not completely free of human impacts, scientists think this marine ecosystem is in a healthy state due to low levels of exploitation of most species. The Tristan economy is based on the local Tristan rock lobster fishery, which provides 80% of the income for local islanders. Additional species of reef fish are caught for subsistence fishing, which is non-commercial fishing by local people to feed their immediate relatives.

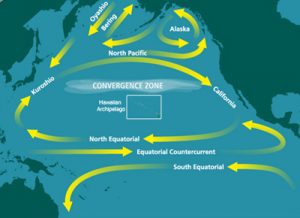

The Tristan islands are located at the boundary between the Southern Ocean and the South Atlantic, and they sit at the confluence of two major currents. Their location may make the islands “hotspots” for marine organisms because these currents may carry nutrients to enhance productivity of the reef communities.

Prior to the present study, not much was known about the marine life at Tristan. Recognizing the need to establish baseline knowledge on the biodiversity and abundance of organisms, the authors of the present study conducted the first quantitative surveys from different depth zones around these islands. By surveying different depths and distances from shore, the authors assessed differences in the abundance and biomass of fishes, invertebrates, and kelps.

How they did it:

At each of the four islands, the researchers recorded the number of individuals of various species of fish and invertebrates at nearshore kelp forests, open water, and deep-water locations. They used SCUBA at the nearshore sites to count the different types of organisms, while at the deeper water locations, they set up GoPro videos to estimate diversity. At each sampling location, the authors also estimated the length of each fish and lobster they observed. These measurements were then used to compute biomass, which is the amount of mass contained in an organism. Biomass is important for marine studies such as this one because it indicates how much energy is available in a food web; therefore, this measure informs scientists on the health of the ecosystem. After collecting the data, the researchers measured fish and invertebrate diversity at each island and compared the communities among the four islands.

Results:

The authors found that the different ecosystems surrounding the Tristan Islands had overall low biodiversity of fish and invertebrates. Nearshore kelp forests had the lowest biodiversity of fish and invertebrates, compared to deeper water locations. Despite the low diversity, the authors were surprised by the high abundances and biomass of fish and invertebrates, indicating that the marine ecosystems surrounding the islands are in a healthy state. The authors found that biomass was consistently high in the kelp forests of all four islands, likely due to the productive algae resources that support abundant invertebrates, which in turn are consumed by fish.

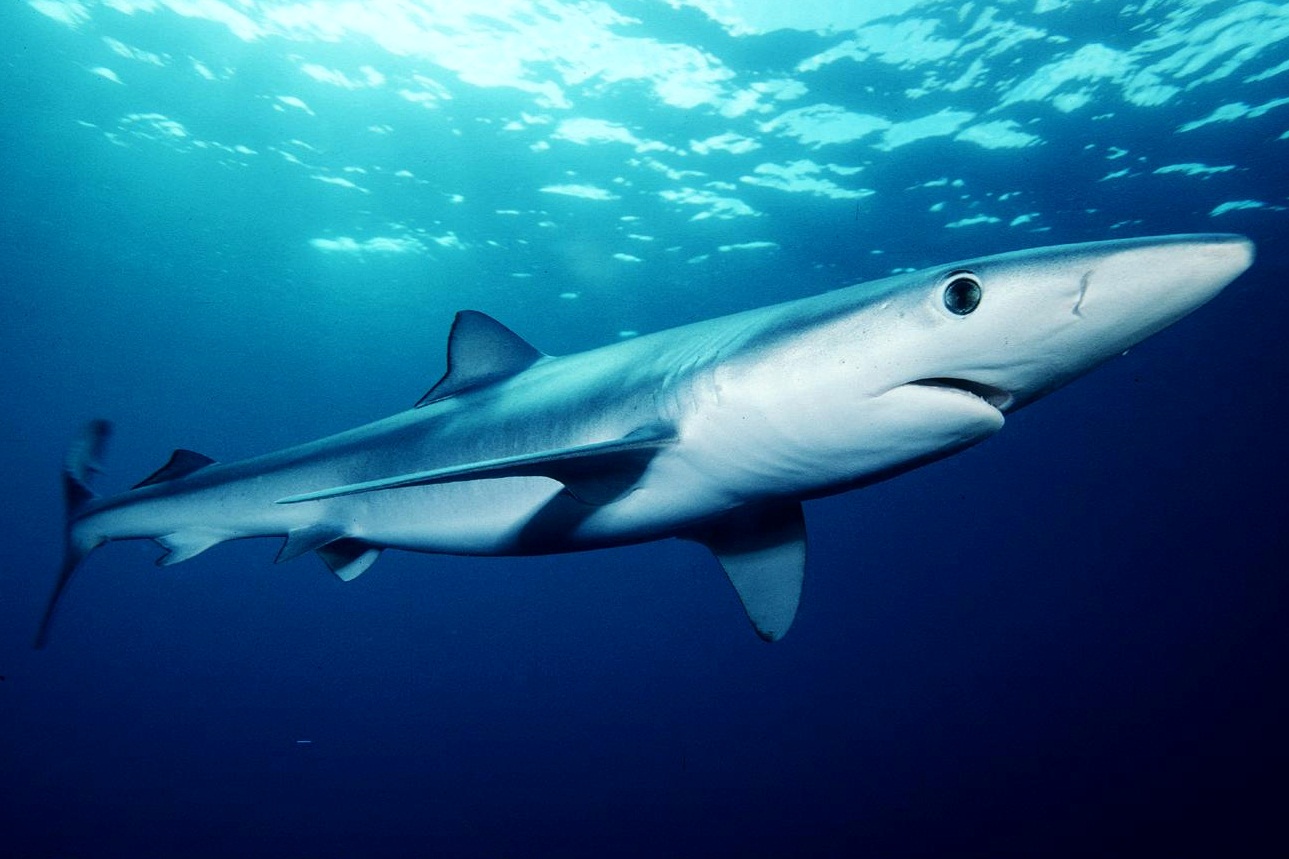

In contrast, the open and deep-water fish communities had high biodiversity, which corresponded with the presence of rocky bottom types such as sea pens, whip corals, and gorgonians. Juvenile Blue Sharks (Prionace glauca) were highly abundant at these sites.

The authors found that fish and invertebrate communities were different at each island. Higher numbers of spiny lobster were found at Tristan and Inaccessible, but significantly bigger lobster occurred in the waters surrounding Gough and Nightingale. The fish and invertebrate communities were most distinct in Gough, where sea temperatures were 3-4° C colder and the water was less saline compared to the other islands.

The bigger picture

Tristan da Cunha Islands are a rare example of a relatively unimpacted marine ecosystem, although characterized by low overall biodiversity. The authors attribute the low biodiversity to the extreme isolation of these islands from other land masses. What is particularly remarkable about these islands is that despite long-term lobster harvesting, lobster abundance at these islands was similar to those found in marine protected areas in other parts of the world!

Due to the unique location of these islands, they are a globally-recognized region for seabirds, whales, tunas, sharks, and seals. Remember how I mentioned earlier that these islands sit at the confluence of two major ocean currents? The three northern-most islands sit north of the Subtropical Convergence. Gough, the southern-most island, is located right on or below this convergence, depending on season.

It is likely that the Subtropical Convergence brings enhanced primary productivity of its waters, which in turn supports invertebrate consumers and top predators. Unfortunately, Tristan da Cunha Islands may be at risk from high fishing pressure, and the coral substrates of the deeper waters could face destruction by bottom trawling gear.

This study is critical because it has contributed baseline knowledge on marine communities in isolated, yet vulnerable, islands. Hopefully, the findings from this study will provide incentive for wise use of marine resources.

Kate received her Ph.D. in Aquatic Ecology from the University of Notre Dame and she holds a Masters in Environmental Science & Biology from SUNY Brockport. She currently teaches at a small college in Indiana and is starting out her neophyte research career in aquatic community monitoring. Outside of lab and fieldwork, she enjoys running and kickboxing.