Kirsten F. Thompson, Kathryn A. Miller, Duncan Currie, Paul Johnston, David Santillo. Seabed Mining and Approaches to Governance of the Deep Seabed. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2018; 5 DOI: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00480

*Title adapted from a line Aragorn says in Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers.

A new frontier is opening up and it isn’t space. It’s a place much less explored and closer to home: the deep sea. While we have a lot to discover about the deep sea, we do know that in the depths of the ocean are a number of valuable minerals and metals like gold, manganese, and cobalt. Yet with so little known, companies are ready to dive into the cold deep, gathering these metals for economic gain. With a few companies having already acquired contracts for deep sea mining, researchers and environmentalists are urging caution and asking for time to refine our understanding of the potential impacts of mining. Dr. Kirsten Thompson and her colleagues remind us that this is a nuanced and complicated problem in their new paper reviewing the intricacies of seabed mining.

Why mine?

The metals and minerals found in the deep sea are incredibly rare, perhaps justifying the level of difficulty and investment required in mining. These materials are frequently used in technology like smartphones and computers, but also in green energy technology like solar panels, wind turbines, and electric vehicles. As countries continue to develop and populations grow, there is an ever-increasing demand for technology. We need green energy more than ever, and extreme weather events serve as a reminder of the impacts of climate change. But we know essentially nothing about the potential environmental and societal risks that come with deep sea mining. Will it harm fragile deep sea ecosystems? Could it harm nearby fisheries that people rely on for food? Could mining impact the amount of carbon the ocean absorbs from the atmosphere, counteracting improvements to green energy? Essentially, is the amount of materials gained from mining worth the risk?

Why should we care about the deep sea?

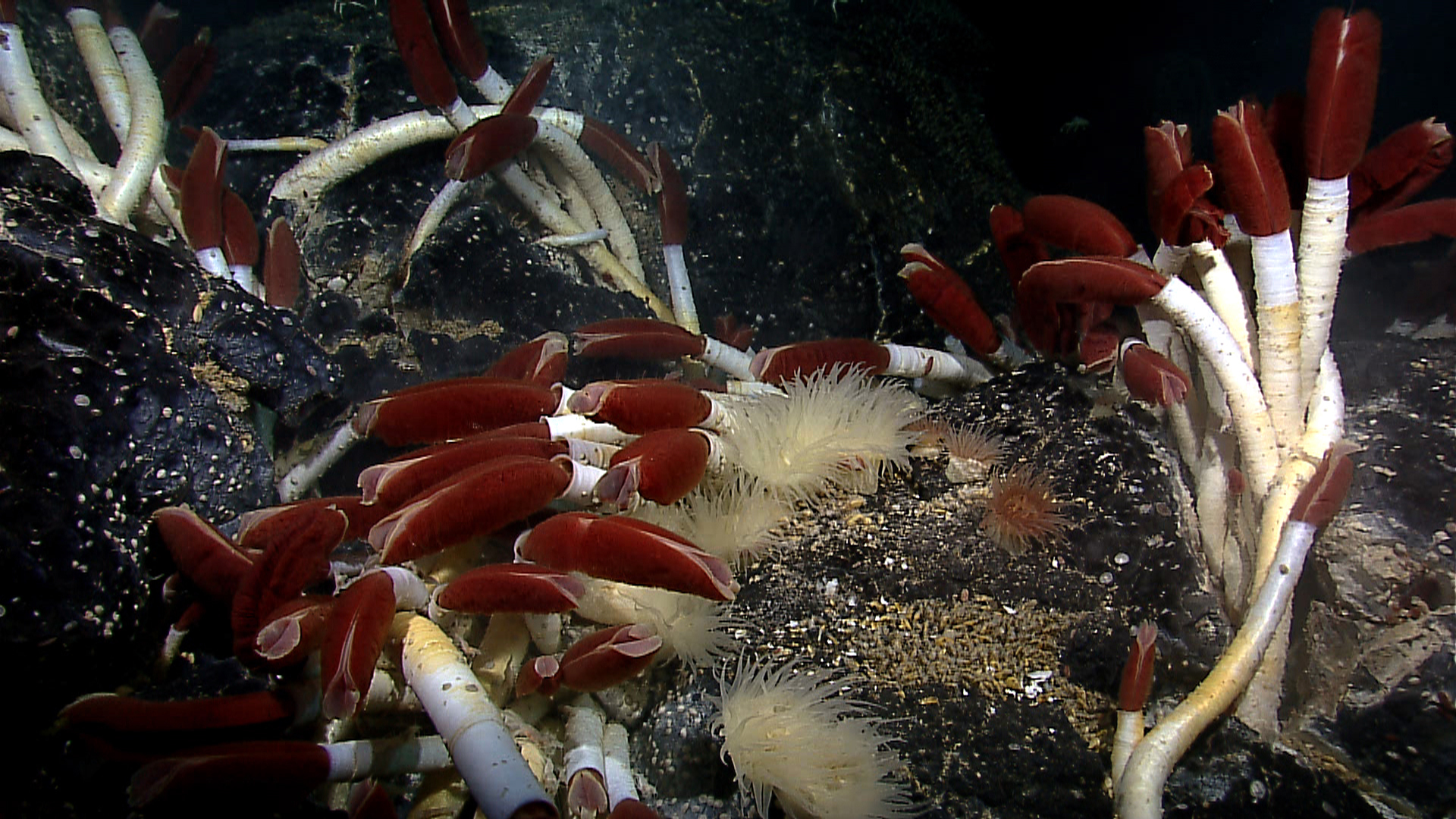

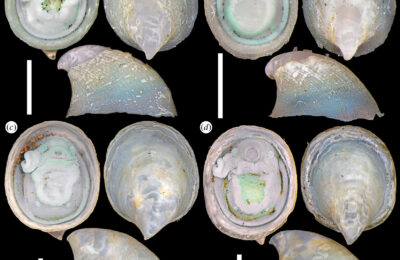

The deep sea is almost entirely unknown, with only about 5% of it having been explored with remote vehicles and less than 0.0001% of the seafloor having been sampled. This is largely due to how difficult it is to navigate the region. As Bill Nye puts it, this is due to the 3C’s: the deep sea is cold, corrosive, and crushing. This makes exploration expensive, but what little we do know has been astounding. The deep sea is where we have found hydrothermal vents, animals that live off of chemosynthesis (making energy out of methane instead of the sun), and where tube worms and crabs live in water shimmering with heat. With some research, who knows what secrets we could discover? The cure for cancer? The next clean energy? A toddler’s next animal obsession? The possibilities are endless.

But we don’t know how mining could impact deep sea ecosystems, or even others. For example, global fisheries are an important source of income and food. Mining could stir up sediment from the bottom of the ocean, which could drift in and out of country boundaries, changing shallower ecosystems. Could this impact fisheries? The little we do know about deep sea ecosystems emphasizes how risky this is to them. Animals in the deep sea tend to live a long time, grow slowly, reproduce slowly, and reach sexual maturity later in life. All of these characteristics makes it difficult for these species to recover from disturbances, much less adapt to change.

Who gets to make these decisions?

Maybe one of the most concerning elements of the approach of deep sea mining is its legal ambiguity. Rights to the seafloor are generally controlled by two groups: countries, which have control over the continental shelves off their coasts, and the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which controls international waters referred to as the Area. ISA uses guidelines outlined by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to make decisions; in this case, they follow Article 140, which states that mining can be done “for the benefit of mankind as a whole.”

But that is the ultimate question. If “benefit” is interpreted economically alone, who benefits? The companies mining would certainly benefit, local governments selling the rights to their resources might benefit, but some people may only see the benefit in job opportunities, and still others might see no benefit at all. How do you measure benefit to mankind as a whole?

What can we do?

At this point, we know almost nothing concretely. There has never been a commercial-scale mining trial, so everything at this point is mostly conjecture. With this in mind, the authors recommend 5 main approaches to help mitigate the possible harm of deep sea mining.

1. Improve sustainability. By improving how we recycle technology, making products last longer, enhancing designs, and being careful with how we use technology, we could make a more circular economy that would decrease our need for these minerals. This would take effort and lifestyle changes.

2. Set up a monitoring network that is independent of those financially invested in mining that will collect data and establish procedures for mining deep sea ecosystems while causing the least damage.

3. Set up a series of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) that could give organisms places to recover and live undisturbed.

4. Be transparent and tell people what is happening in their community so that they have a say, especially indigenous groups and small island nations who are likely to be greatly impacted by these decisions.

5. Ensure that there is an independent, governing body, like ISA, that can stop mining should it prove to be damaging.

Without these steps, we risk rushing into a situation we don’t understand—one where the economic, social, and environmental consequences could be with us for many years. We have seen the consequences of seeking treasures in the depths of the sea, like the horrific aftermath of the Gulf Oil Spill. Even barring a meltdown like that of oil spills, we could still cause irreparable damage to an ecosystem whose worth we haven’t even begun to understand, and we could harm fisheries and livelihoods in the process. With so much at stake, is it worth the economic “benefit?”

I am a PhD student studying Biological Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography. My interests are in food webs, ecology, and the interaction of humans and the ocean, whether that is in the form of fishing, pollution, climate change, or simply how we view the ocean. I am currently researching the decline of cancer crabs and lobsters in the Narragansett Bay.