Chen, C., Hilário, A., Rodrigues, C. F., & Ramirez-Llodra, E. (2022). Integrative taxonomy of a new cocculinid limpet dominating the Aurora Vent Field in the central Arctic ocean. Royal Society Open Science.

The life history of a species and how it came to be can be a mystery. What kinds of trials and tribulations has a species overcome? How has the changing environment over millennia affected their existence? Scientific research can shed light on how certain organisms may have successfully adapted in the face of great change or extreme environments. One such extreme environment, found in the Central Arctic Ocean, is rarely studied due to its location permanently under ice and nearly 4000 meters underwater.

It’s the Aurora Vent Field, and an area deep in the Central Arctic Ocean marked by hydrothermal vents scattered across the seafloor. It’s extremely dark, under immense pressures, and near freezing temperatures, yet this vent field is a highly unique and productive environment seen nowhere else on Earth. Known as a chemosynthetic ecosystem, the organisms around hydrothermal vents get energy using a process called chemosynthesis to break down the chemical compounds vents spew out, like methane and hydrogen sulfide, instead of using light like plants. This proves to be a home to some rare organisms that enjoy living the extreme lifestyle, which is what researchers aboard the vessel Kronprins Haakon found on a research trip in October of 2021.

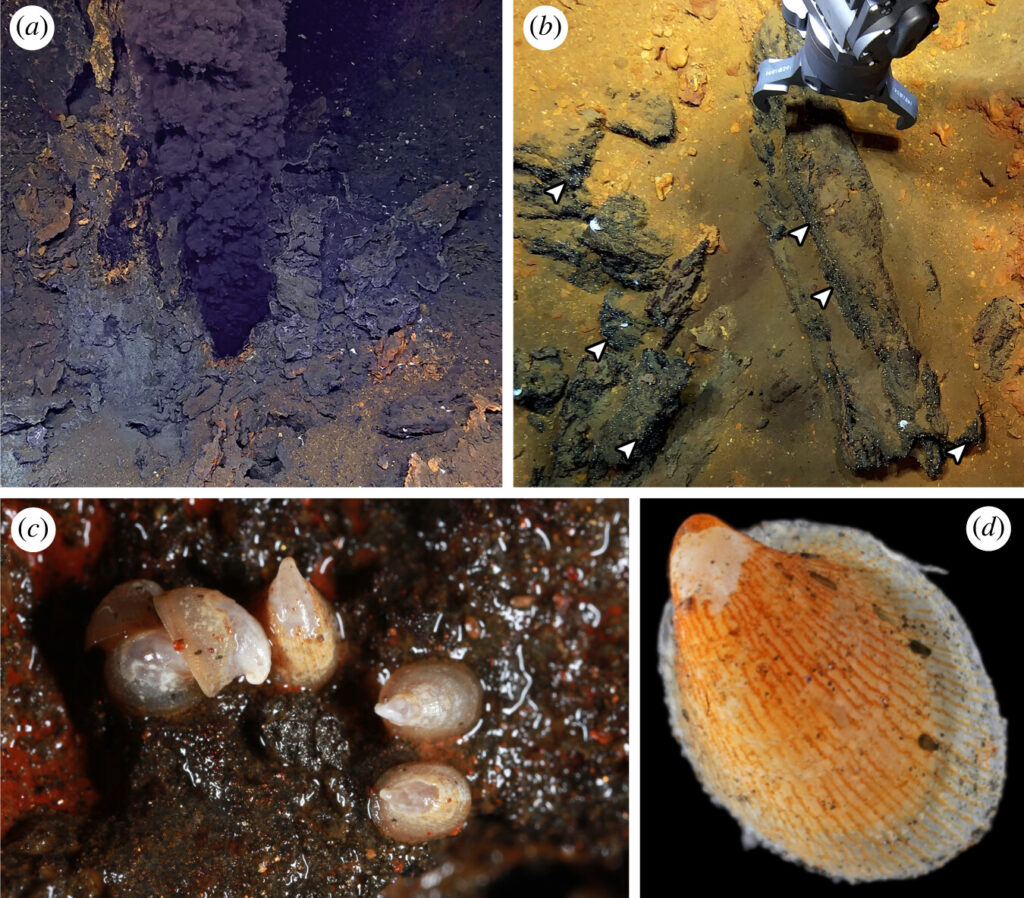

Photo: (a) a “black smoker” vent, (b) the ROV collecting a piece of sulfide chimney, with arrows indicating cocculinid limpets, (c) limpets on chimney surface after recovery on-board, and (d) A live limpet viewed under a microscope. Source: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rsos.220885

Using a remotely operated vehicle with an arm, deep sea scientists were collecting biological samples of the “black smoker” vents – named Hans Tore and Ganymede – and found them covered in clusters of white, round shells. Using these samples, a 3D rendered model of the creature’s form was created to study its morphology and elucidate its identity. DNA was extracted in order to analyze genes, close relatives, and how this specific limpet came to find itself inhabiting a plume of chemicals thousands of meters below a permanent layer of ice.

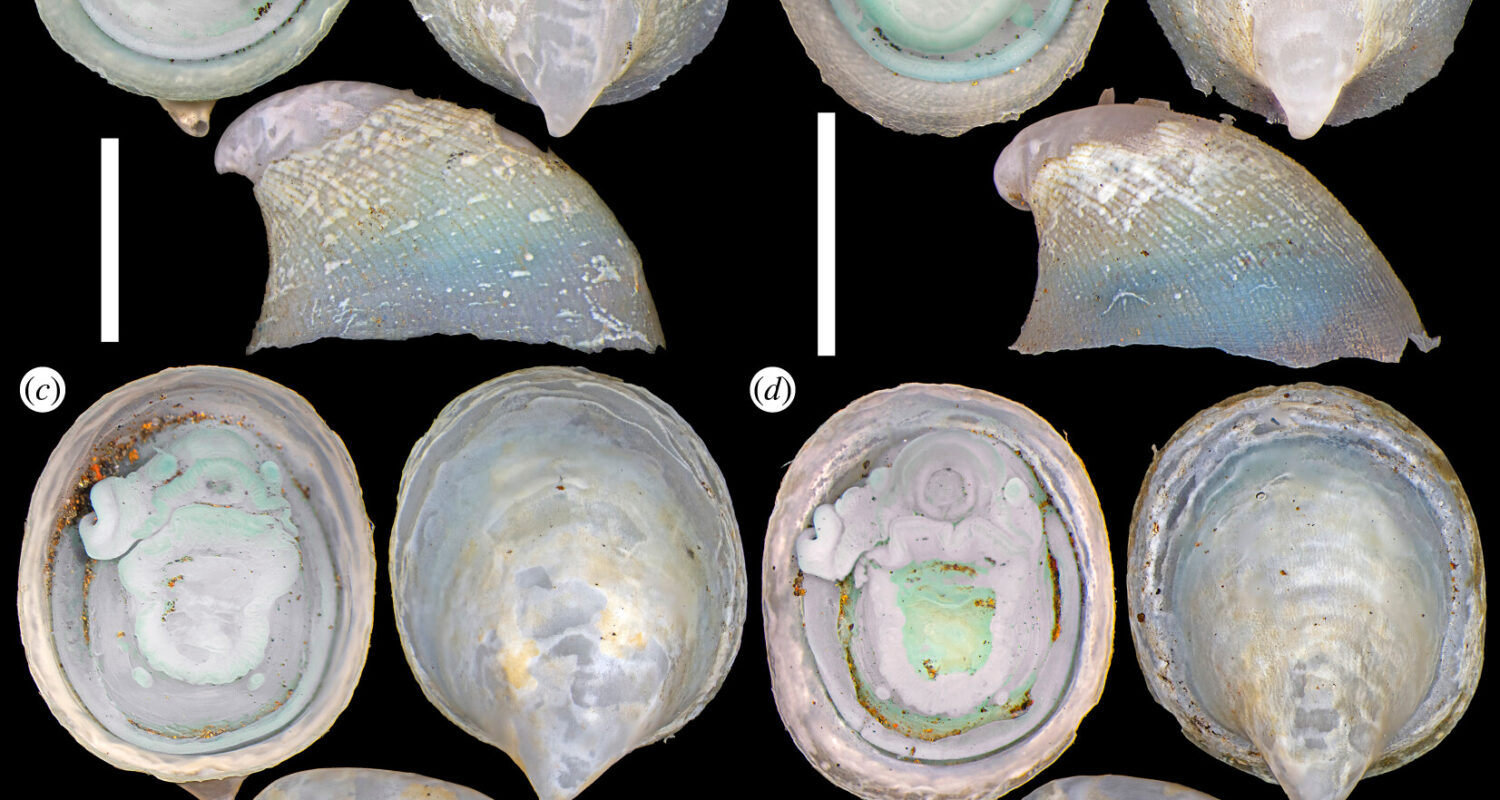

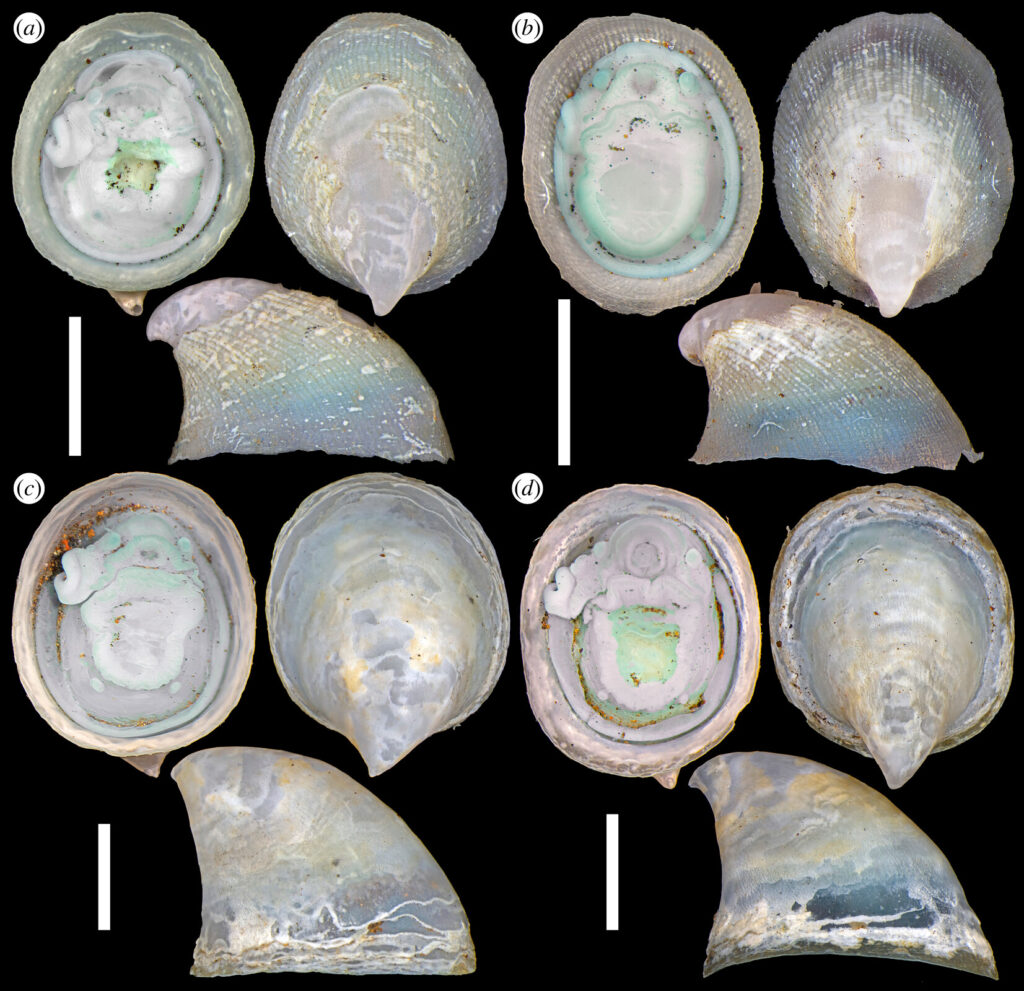

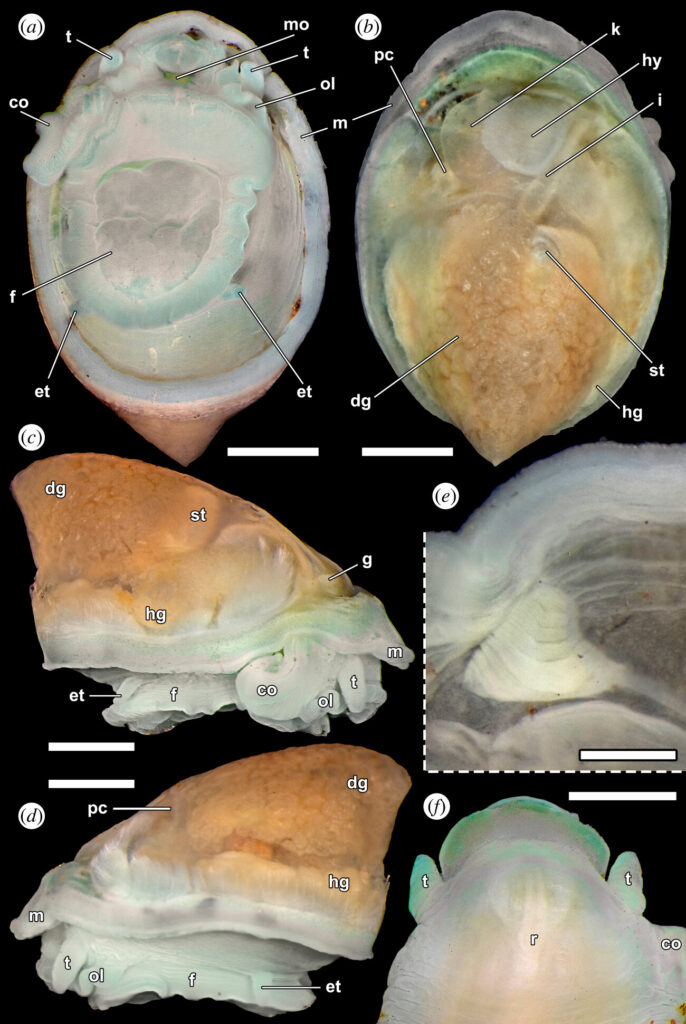

Photo: A Cocculina aurora in different views under a microscope. Source:https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rsos.220885

Photo: A Cocculina aurora in different views under a microscope. Source:https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rsos.220885

They discovered this was a novel limpet species, a mollusk of the family Cocculinidae, which they decided to name Cocculina aurora. They are a relative to the sea snail and distinguished by a single round shell and muscular foot, usually stuck fast to a surface of choice like rock, wood or other marine animal. It’s difficult to determine a species true genetic affiliation when there’s little data on the morphology and genes of their relatives, but researchers were able to confirm this species novelty and its placement in this mollusk family. While relatives are usually found living on other surfaces, this isn’t the first time a cocculinid limpet has invaded the hydrothermal vent scene; the close relative C. enigmadonta is the only other cocculinid species to finds its home in vent ecosystems, coincidentally in the complete opposite Antarctic Ocean. This limpet’s diet appeared to be bacteria mixed with the occasional sulfide particle, so it was likely feeding on the vent’s chimney surfaces. But what makes this species especially illuminating to scientists? The answer is, metaphorically speaking, in its tongue.

Photo: a close up view of the cocculinid limpet and its radula, noted by (r.) in the bottom right corner. Source:https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rsos.220885

Photo: a close up view of the cocculinid limpet and its radula, noted by (r.) in the bottom right corner. Source:https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rsos.220885

The aurora evolved from a specialized cocculinid species that inhabits wood falls, when fallen trees wind up in the ocean and become hot spots for organisms to latch on and benefit from sweet safety and resources. This means that at some point during its life history, this humble limpet had to take an evolutionary leap and went from munching on tree bark to bacteria in one of the most extreme niches on earth. The key to its success was likely its adapted mollusk tongue, or radula. Analysis of its body form showed that instead of large, strong outer teeth on its radula for chewing wood, the aurora’s tongue had reduced outer teeth that were modified to allow it to make better contact with vent surfaces and graze down swaths of bacteria. Thus, the Aurora Vent Field became home sweet home for this surprising extremophile.

Discoveries like this are a testament to the wonders of evolution, the never ending saga that every living organism faces simply due to existence. The never ending, twisting paths of adaptation influences all of life, but no environment is too harsh, no niche too small for it to find a way to cling to whatever resources it can. Perhaps it can also lend insight into how the current world may too be able to find ways to adapt to a rapidly changing climate. Either way, the aurora is an icon for evolution, and its unique presence in the Aurora Vent Field is an essential component to the stability of this extreme ecosystem.

I’m a California native with a lifelong curiosity for all things related to the ocean. I got my bachelors in Marine Biology from the University of California Santa Cruz, and I’m currently pursuing a masters degree in Animal Science at the University of Idaho where my main focus of study is fish nutrition in aquaculture. My favorite subject to study outside of school is the deep sea. I enjoy learning about new mind boggling species, the latest discoveries of the deep, and the history of deep sea pioneers, research and technology. If I’m not studying the mysteries of the ocean, I’m probably roller skating or watching scary movies.