Still living with your mom? Nothing to be embarrassed about – especially if you are a sperm whale!

Sarano, Francois, et al. “Kin relationships in cultural species of the marine realm: case study of a matrilineal social group of sperm whales off Mauritius island, Indian Ocean.” Royal Society Open Science 8.2 (2021): 201794. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.201794

Just like humans, many animals live in families. And just like with humans, their families come in many forms and sizes.

Whales in particular stick with their kin, with multiple generations of a single whale family feeding, hunting, and gliding through the ocean together. Scientists can speculate that several whales spending a lot of time together belong to the same family – but they don’t know how exactly those whales are related to one another. Do grandparents babysit their grandcalves? Do family reunions bring cetacean cousins together to feast on fish?

With whales, it can be hard to tell.

Through observation, scientists can make note of adult females with their calves. But beyond that, scientists can have trouble teasing out familial relations; aside from markings like scars, most whales look very similar to each other, at least to humans. This is where biology comes to the rescue.

No skin off a whale’s back

A great way to study blood family relations is through DNA analysis. It is easy for humans. All we have to do is mail a cheek swab to a genealogy company! But to collect samples of whale DNA, scientists have to get creative.

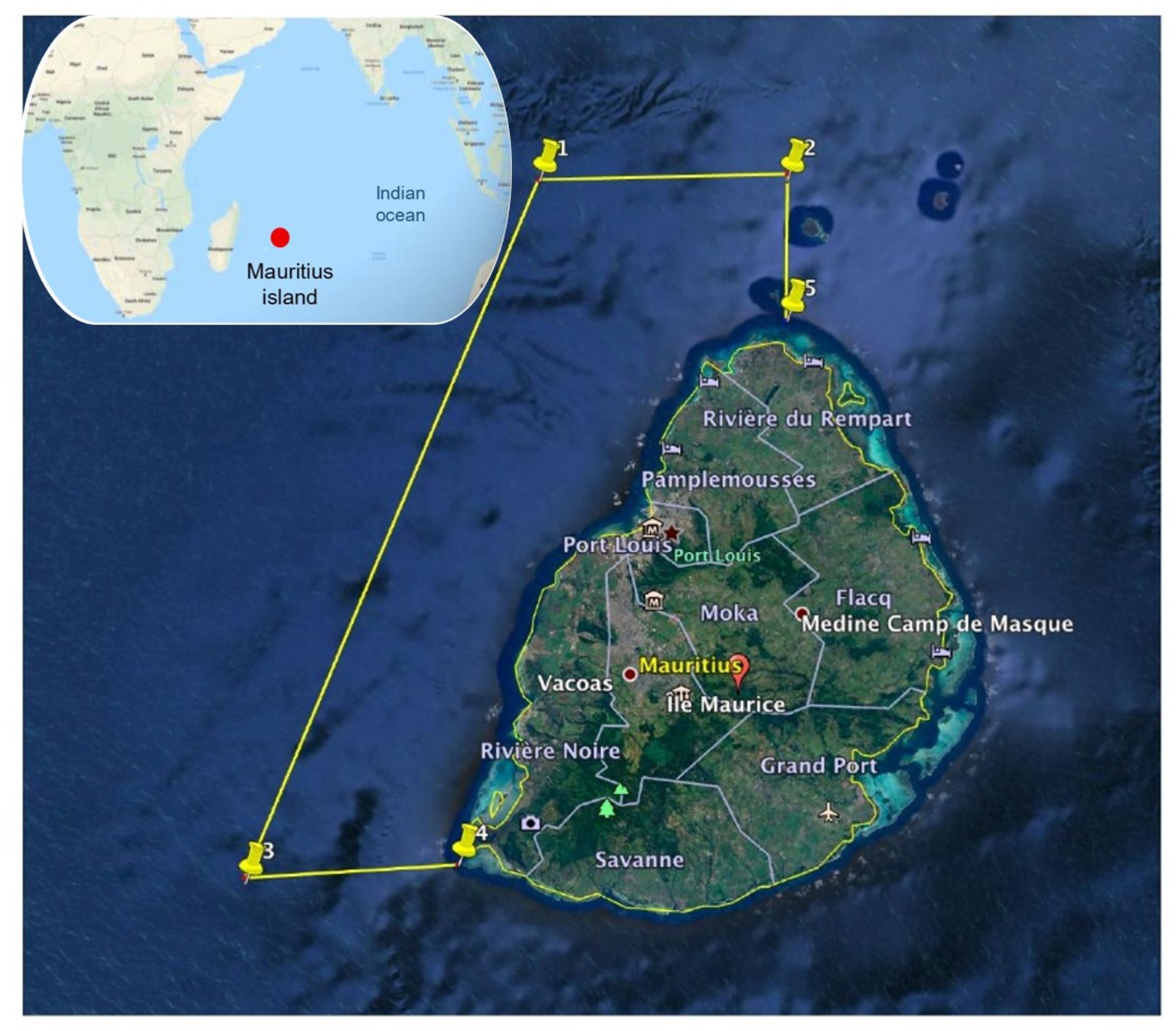

A team of Mauritius Island-based researchers set out to study their local sperm whales in a project called Maubydick (get it?). To uncover the familial ties in a population of approximately one hundred sperm whales, the team collected their skin.

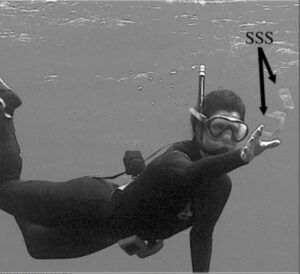

Skin shedding is normal for many animals. Human skin sheddings become dust and collect behind the couch. Whale skin bits just drift with the current. Taking advantage of that, the researchers went snorkeling out in the ocean, waited for the sperm whales to swim by, identified them by their markings, and grabbed whatever skin pieces had sloughed off.

The scientists then looked how the whales were related to each other by analyzing their mitochondrial DNA. Unlike the vast majority of DNA, which is tightly coiled in a cell’s nucleus and comes from both parents, mitochondrial DNA resides in mitochondria – parts of the cell that produce energy. This tiny bit of genetic code is inherited from the mother. Because it doesn’t change much between generations, scientists can use it to trace relations and sketch family trees.

Like mother, like daughter

This population of sperm whales counted 17 female sperm whales and 11 calves. This lack of adult males makes sense, because male sperm whales (much like other whale species) usually leave their mothers before they even become sexually mature. To sketch the family tree, the scientists gave all the whales nicknames.

All but one whale in this group shared parts of mitochondrial DNA, meaning that they were related through their mothers. Possibly, they were all descended from one female sperm whale who is no longer alive. Her daughters or granddaughters, whales nicknamed “Dos-Calleux” and “Issa,” gave rise to the remainder of the group.

Just one female sperm whale, “Claire,” wasn’t related to the rest of the group. She didn’t interact much with them, either. The scientists weren’t sure why she hung out with the other whales, but supposed that she might have been “adopted” by the group.

Whale families tend to be matrilineal, or based on the female line. The Mauritius researchers showed that the sperm whales of their local population are no exception and that female whales are the rock of their families.

The scientists also discovered that sometimes females who cared for calves, such as by letting them nurse, weren’t actually their mothers. An adult female nicknamed “Emy” had been thought to be the mother of a young male calf “Alexander,” but this study uncovered that they weren’t related. “Alexander’s” actual mother, pinpointed through DNA analysis, was rarely seen spending time with her calf. These family dynamics means that it’s hard to determine relations among whales just by observing them and DNA analysis is the way to go for understanding family matters in the ocean.

I am a PhD candidate at Northeastern University in Boston. I study regeneration of the nervous system in water salamanders called axolotls. In my free time, I like to read science fiction, bake, go on walks around Boston, and dig up cool science articles.