Have you ever wondered what happens to the garbage that ends up in the ocean? Or about what just might eat this garbage thinking it might have been food? That what the scientists in this study looked at in Brazil. These scientists looked at the gut contents of several fish to see what they ate.

Picture Credit: NOAA Marine Debris Program.

Why would anything want to eat plastic?

It is not so much about wanting to eat the plastic or any other kind of trash floating around in the ocean, but about what they may look like to an animal passing by. If you saw a plastic bag drifting along a current, can you think of anything it might look like? Perhaps, a large, tasty jellyfish to a sea turtle? Now, going to why the scientists are worried about fish, a lot of fish eat really small animals called plankton. These plankton are typically transparent in the water column, but so are many types of microplastics. These fish eat the microplastics, thinking they are food, but get no nutritional value from them. Not only that, but the ingestion of plastics can make animals think they are full because of their stomachs being full of nondigestible material, as well as potentially carry toxins into the organism. Microplastics can have toxic material that is adhered to their surface be ingested by the fish. This toxic material is in turn incorporated into the tissues of the fish. If this fish gets eaten by larger fish, then a shark, or a human, these toxins can accumulate up through each level. This process is known as biomagnification, and it’s a real concern for people and animals who love to eat fish.

Fish Guts

The scientists involved in this study looked at three types of fish: pelagic (fish living and feeding in open water away from the seafloor), demersal (fish living and feeding near or on the bottom sediments), and demersal-pelagic (fish that rotate or alternate between these two lifestyle strategies).

What they found was that pelagic fish, especially the skipjack tuna, had the highest amount of plastics found in their gut when compared to the other types of fish. Meanwhile, the demersal fish had the lowest amount of plastics recorded from their gut contents. It must be noted though that all the fish observed in this study did have plastics present in their guts. The quantity of the plastics within the stomachs is what varied among the fish. The demersal fish only had microplastics contained within their guts; meanwhile, the other fish had larger plastics present as well.

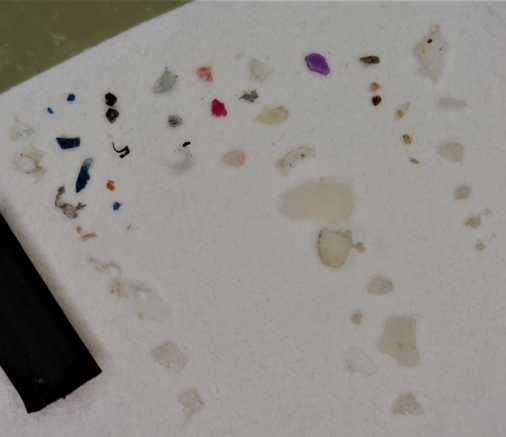

Another thing that these scientists were interested in was to see if the color of the plastics had an impact on which ones were eaten. Transparent (69 items), black (52 items), and blue (50 items) were the most common plastic colors ingested by the fish. Other colors found included white, red, green, and gray; however, all of these were present in way lower numbers (< 20 items). This color selection was consistent across all the fish types studied.

As mentioned previously, the ingestion of transparent plastics makes sense because a lot of the fish’s natural food source is transparent in the ocean.

What does it matter?

Many of the fish we eat are pelagic (tuna for example). If these animals are eating plastics, we could inadvertently be impacted by these plastics through the biomagnification of toxins accumulated in the fish’s tissues. This has not been demonstrated yet, but it is of concern and more people are researching this topic. In addition to this, the fish, as well as many other animals, can experience negative (even fatal) effects from plastic ingestion.

How to Help

So, what can you do to help reduce the number of microplastics in the ocean? You can follow the reduce, reuse, recycle, and refuse concepts. Refuse is a bit newer and demonstrates how you can refuse to use certain products, like a single use straw and instead purchase a reusable one that you keep with you on the go. Another thing is to look carefully at the ingredients on the back of the products you use. Polyethylene is another label for plastics or plastic beads. These used to be common in a lot of cosmetic products, but there is legislation in effect to remove these microbeads from commercially available products. No matter what though, the more you know about the products you use, the more sustainable and environmentally aware you can be!

Article:

Neto, J.G.B., Rodrigues, F.L., Ortega, I., Rodrigues, L.D.S., Lacerda, A.L., Coletto, J.L., Kessler, F., Cardoso, L.G., Madureira, L., & Proietti, M.C. (2020). Ingestion of plastic debris by commercially important marine fish in southeast-south Brazil. Environmental Pollution, 267, 115508.

Hello! I’m a PhD student at the Florida Institute of Technology. The lab I work in focuses on ecological engineering along with marine corrosion and biofouling control. I’ve enjoyed working in the fields of environmental education and outreach. When I’m not working in the lab, I enjoy reading, volleyball, and photography.