Paper: Pietsch TW (2005) Dimorphism, parasitism, and sex revisited: Modes of reproduction among deep-sea ceratioid anglerfishes (Teleostei: Lophiiformes). Ichthyol Res 52:207–236 (Open access!)

Most people, when they think of deep sea fish, think of that crazy fish from Finding Nemo with the big teeth and the light on its head: the anglerfish’s big shining cinematic moment (Figure 1). The folks at Disney Pixar weren’t exaggerating or exercising their imaginations; that kind of fish really does exist in the deep ocean, and it’s even weirder than you think it is.

The anglerfishes are widely regarded as some of the ugliest creatures in the ocean but, like all of us, they must find love too (Figure 2).

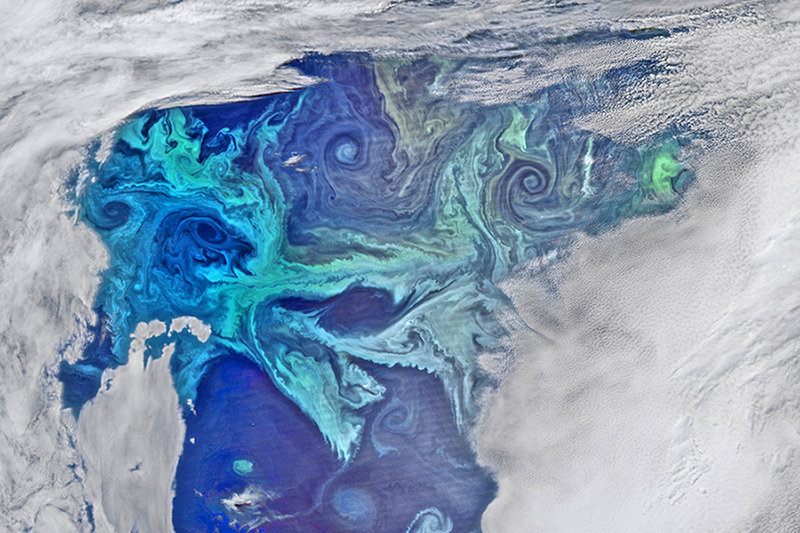

They live in the deep parts of the ocean that get hardly any sunlight (300+ meters deep) and have hardly any fish living there compared to the surface ocean due to a small food supply. The deep ocean can’t sustain a lot of fish because there aren’t any plants – photosynthesis is impossible below 100m. Without that photosynthetic base of the food chain so abundant like it is in the surface ocean, the fish that do live there have to survive on a smaller number of other fish to eat, and those smaller fish survive on a diet of marine snow: organic matter that rains down on the deep from the abundant surface oceans.

Because of all that, it’s tough for anglerfish to find a mate: not only is it pitch dark down in the deep, but there also aren’t a lot of anglerfish of their species swimming around – it’s hard to have a “meet cute” to find their next mate! The anglerfishes have evolved a fascinating way to get around this potentially major problem: sexual dimorphic parasitism.

Let’s dissect that term, sexual dimorphic parasitism. You’re all familiar with sexual, no doubt, so we’ll start with dimorphic. Literally “different shapes”, dimorphism (major differences between size in males and females) is a relatively common thing in the animal kingdom. Elephant seals are a common example; the males can weigh up to 8800 lbs, and the females only get to 2000 lbs. The anglerfish, though, takes sexual dimorphism to an extreme. For a while, scientists didn’t even recognize male anglerfishes as part of the same family as females. The females can be up to 60 times the length and half a million times the weight of their male counterparts, and they look almost nothing alike. The females of the species have small, underdeveloped eyes and noses with a long piece of bioluminescent skin (called an esca) that acts as a lure to attract their prey. In contrast, the males have large, well-developed eyes and nostrils and no lure (Figure 3).

The reason that they’re so differently shaped is related to their reproductive strategy. When males are born, they’re born with a giant liver that helps to sustain them for a few months without feeding (analogous to the yolk sac of other animals). That giant liver helps them on their sole quest in life: to find a female. Their well-developed eyes search in the inky blackness for the species-specific bioluminescent lure of their true love. Their well-developed sense of smell helps them sniff out the species-specific pheromones that she leaves behind, like a trail of perfume, as she swims through the ocean.

Once the male finds his beloved female, the parasitism part of their reproductive story begins. Instead of a bioluminescent lure, the males of most anglerfish species have a well developed rostrum, a glorified pointy piece of skin on top of their heads, as well as specially developed denticles (a kind of teeth). The male finds his female, and then, to ensure that she never leaves him, bites her on her side and hangs on for dear life. As the days pass, he continues to grasp on with his denticles, and the two undergo the attachment. The male’s skin around his mouth starts to grow quickly towards the female, eventually fusing to her skin (Figure 4). Then the female’s blood vessels will grow into that fused tissue, essentially connecting the male to her circulatory system. At this point, in some species, the male’s testicles begin to increase in size and mature. The fusion is complete and the happy couple will now be together forever.

The parasitic male is now fully integrated into the female’s circulatory system and depends on her to provide all of his nutrients. He brings his fully developed testes to the table and the two can now spawn whenever they wish (the male fertilizing the egg sheet that the female lays in the open water), without having to do all the work of searching for another mate. Till death do they part! (Figure 5)

Hi and welcome to oceanbites! I recently finished my master’s degree at URI, focusing on lobsters and how they respond metabolically to ocean acidification projections. I did my undergrad at Boston University and majored in English and Marine Sciences – a weird combination, but a scientist also has to be a good writer! When I’m not researching, I’m cooking or going for a run or kicking butt at trivia competitions. Check me out on Twitter @glassysquid for more ocean and climate change related conversation!

Hi I love the article it is very pleasant to read and I did not want to stop. One thing there is a spelling mistake where you speak of smell “Their well-developed sense of small”