Have you ever wondered about how marine animals travel to a new place, you know, when they can’t swim there? Phorcus sauciatus, a marine top snail, doesn’t swim around like a fish. As an adult, this snail’s only method of movement is by crawling around on a surface with its foot. So how does this top snail move from an area like the Canary Islands right off the coast of Africa to the Azores when it was never seen there before 2013?

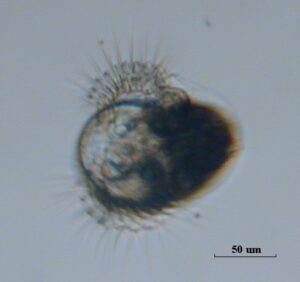

This top snail lives for a short time as plankton, a lifestyle where the small animals drift with currents since they are not strong enough to constantly swim against them. When the larvae hatch from eggs, they are at the mercy of the currents. Then just after six days, the larvae metamorphosizes into a juvenile snail.

This juvenile snail moves around just as an adult, crawling along the surface with its foot. When a planktonic larval organism spends only a short time as plankton, it is referred to as being lecithotrophic, which means there is enough yolk within the egg for the animal to metamorphose into its juvenile form quickly. Being plankton is dangerous since plankton are a food source for a variety of animals and cannot exactly swim away from a predator. So, the faster a planktonic organism can grow, the safer it will be. However, this short period of time as plankton also means that these snails cannot travel very far from their fertilization and hatching points. They tend to stay local and do not easily disperse to far away areas without external assistance (like humans).

A Whole New World

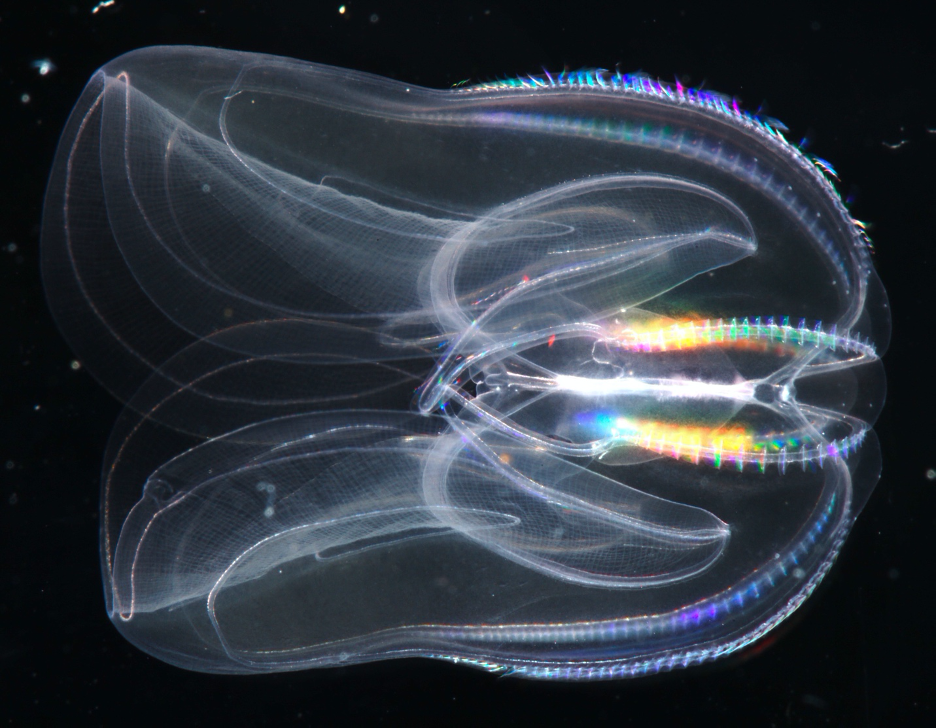

There are a variety of ways for plants and animals to arrive in a new area. They could progressively move from one location to another (an awfully slow process) or they could settle on a boat or be introduced to a new area by humans. However, throughout history, many isolated islands have been colonized by new plants and animals by chance (for example being transported by a random event like a massive storm). One way this happens is through rafting. Rafting occurs when plants and animals attach to a surface (like a piece of driftwood) and float along with the currents until they wash up into a new area, much like a boat ride.

One Small Step for a Snail, a Giant Leap for the Population

The presence of the top snail in the Azores is not the inconceivable. However it is surprising that the population proliferated within five years. In July of 2013, seven individuals of the top snail species were found in the intertidal rocky areas of Santa Maria Island. One year later, 668 individuals were found in the same area. This means there was about a 9400% in the population during this five-year period. This proliferation of snails (which were of various ages) demonstrates that the top snail population officially colonized the area and became an established community. In 2013, top snails were also seen for the first time in the neighboring island, São Miguel.

Snail Ancestry

Top snails were collected from the Azores islands of Santa Maria and São Miguel as well as from areas where these snails are naturally located. The DNA of the snails were extracted and compared to one another to determine which snail types had the most similar genetic information. Essentially, the scientists in the study were trying to determine where there animals most likely came, kind of like how people trace their own ancestry back through DNA. The scientists found that the top snails from the Azores were similar to the ones from Madeira and the Canaries. However, they were just a bit more closely related to the top snails from the Canary Islands, meaning that is likely where they came from.

Travel Plans

While these animals mostly likely did not travel to the Azores as plankton, they may have gotten there by rafting. The Canary Current off the coast of Africa produces a lot of eddies (a branch off from the water current that rotates in various directions). These eddies most likely trapped the rafting organisms within them and eventually transported them to the Azores. Why didn’t this happen earlier? Rising sea surface temperatures have slowly been altering the flow of the ocean. With climate change, the Canary Current has begun to meander more from side to side, producing more eddies and helping the entrapped top snails to travel further than ever before. As climate change continues to increase the temperature of the sea, more animals are going to be distributed to new areas outside of their past distributions. Some of these new arrivals may be problematic, but other may just become an innocent new addition to the backdrop of the local community.

Article: Baptista, L., Santos, A. M., Melo, C. S., Rebelo, A. C., Madeira, P., Cordeiro, R., … & Ávila, S. P. (2021). Untangling the origin of the newcomer Phorcus sauciatus (Mollusca: Gastropoda) in a remote Atlantic archipelago. Marine Biology, 168(1), 1-16.

Hello! I’m a PhD student at the Florida Institute of Technology. The lab I work in focuses on ecological engineering along with marine corrosion and biofouling control. I’ve enjoyed working in the fields of environmental education and outreach. When I’m not working in the lab, I enjoy reading, volleyball, and photography.