Originally posted March 2019

Source: Clark, M. R., Bowden, D. A., Rowden, A. A., & Stewart, R. (2019). Little Evidence of Benthic Community Resilience to Bottom Trawling on Seamounts After 15 Years. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6(February), 1–16. http://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00063

Rebounding from habitat destruction

It is often said that time heals all wounds, but what about the wounds we inflict on Mother Nature? Ocean ecosystems are vulnerable to damage from myriad threats, including underwater mining, pollution, and destructive fishing practices. Bottom trawling is a particularly destructive fishing method, in which a net is weighted down and dragged across the seafloor to indiscriminately collect animals living on or near the bottom of the ocean. In search of fish and crustaceans, bottom trawling lays waste to the seafloor, tearing up rocks and the animals living on them (also called the “benthic community”), thereby damaging critical components of the ecosystem other animals rely on for food and shelter.

Despite being notoriously destructive, bottom trawling remains a popular fishing method responsible for catching around 25% of all wild-caught seafood. Some shallow-water ecosystems appear to recover from bottom trawling damage within 2 – 6 years, but scientists are skeptical that deep-water ecosystems, such as seamounts, and their long-lived or fragile species, like corals, will be able to recover so readily.

Seamounts: hotspots of biodiversity in the deep sea

Seamounts are underwater mountains that raise over 1000 m (3200 feet) above the surrounding seabed. These underwater mountains form important habitats that are considered hotspots of biodiversity, acting as aggregators for a variety of animals, including highly sought-after fishes. Located 100s to 1000s of feet below the ocean surface, seamounts are home to fragile, deep-sea species like deep-sea corals and sponges. Many of these animals grow slowly, live for a very long time (some coral colonies can live 1000s of years), and produce few offspring. These species are more susceptible to damage since they cannot recover, rebound, or reproduce as quickly as their shallow-water relatives.

Yet, seamounts are in danger of habitat destruction just like shallow water habitats. Mining has already started at some seamount locations and some 80 species of fishes are commercially fished off of seamounts around the world – often they are harvested with bottom trawls. A team of scientists from the National Institute and Atmospheric Research in New Zealand decided to investigate how long it would take seamounts to recover from trawling damage (to learn more about how bottom trawling can damage seamounts, watch this video).

How long will it take for seamounts to heal from fishing?

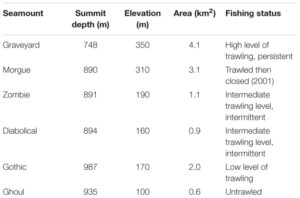

The team, led by Dr. Malcolm Clark, used a group of seamounts in New Zealand, called Graveyard Knoll, as a natural experiment. The seamounts in this area (cleverly given names like Ghoul, Morgue, or Zombie) experience different levels of fishing, allowing the scientists to compare the animal communities between the seamounts to investigate trawling damage. The scientists singled out 6 of the 28 seamounts in Graveyard Knoll and monitored them over a 14-year period. The 6 seamounts experienced different levels of trawling: ranging from none to continuous, heavy levels of trawling. One of the 6 seamounts was of particular interest to the scientists: Morgue was a once heavily trawled seamount that was closed to trawling activity in 2001.

Because the Morgue seamount had been closed to trawling immediately before the scientists began their surveys, they were able to see just how long it would take for a historically heavily trawled seamount to recover. They were also able to compare the community to seamounts that experienced heavy, intermediate, and low levels of trawling. The scientists expected that as time passed, Morgue would begin to look less and less like a heavily trawled seamount and more and more like the seamounts that experienced lower levels of trawling.

Dr. Clark and his team monitored the 6 seamounts 4 times between 2001 – 2015 (in 2001, 2006, 2009, and 2015). The scientists took underwater video footage of the seamounts, towing a camera from the summit of the seamount to its base (mirroring the path of trawlers on seamounts). After completing the transects, the team analyzed the video footage to determine the substrate composition of the seamount (for example: mud, dead coral rubble, or live coral colonies). They then identified and counted all of the invertebrates living on the seamount (such as sea cucumbers, sea stars, corals, and sponges).

Fishing pressure reduces diversity for years to come

Overall, the scientists found that the animals were less abundant and less diverse at the heavily trawled seamounts than at those that experienced low or no trawling. This is not surprising, given the destructive nature of trawling. More shocking were the results from the Morgue seamount, which scientists expected to see recover over the 14-year survey period. Despite the fact that Morgue was closed to trawling activities, scientists saw no signs of recovery. The community on the Morgue seamount continued to look like that of the continually trawled seamount (Graveyard), even 14 years later. This is more than double the time it took shallow-water ecosystems to recover from trawling activity in previous studies.

Unfortunately, we still know very little about just how devastating trawling can be to fragile deep-sea habitats. This study showed that even in lightly trawled areas, slow-growing coral colonies can be wiped out after only a few trawls. Furthermore, this research shows just how persistent the damage from trawling is, with no signs of recovery present over a decade after trawling stops.

Seamounts are likely becoming irreversibly damaged by our fishing practices before we know the full consequences of our actions. As it stands, we have explored less than one tenth of a percent (that is 0.01%) of the seamounts around the globe. With many seamounts located in international waters, it is extremely difficult to manage fishing practices and protect these sites. Nonetheless, it is important that we consider how fishing impacts these hotspots for biodiversity, which support important food-fish and may be housing the very species that can help us cure cancer or find clean energy sources. We simply do not know the potential of these areas we are demolishing or what the consequences their destruction will be for the surrounding environment or our own species.

While this seems like a mountainous issue, you can help protect seamounts by supporting the designation of marine protected areas (or explore and nominate protected Hope Spots) and avoiding buying and eating fish caught in seamount bottom trawls, like orange roughy.

I received my Master’s degree from the University of Rhode Island where I studied the sensory biology of deep-sea fishes. I am fascinated by the amazing animals living in our oceans and love exploring their habitats in any way I can, whether it is by SCUBA diving in coral reefs or using a Remotely Operated Vehicle to see the deepest parts of our oceans.