Article

Bradley M. Norman, Jason A. Holmberg, Zaven Arzoumanian, Samantha D. Reynolds, Rory P. Wilson, Dani Rob, Simon J. Pierce, Adrian C. Gleiss, Rafael de la Parra, Beatriz Galvan, Deni Ramirez-Macias, David Robinson, Steve Fox, Rachel Graham, David Rowat, Matthew Potenski, Marie Levine, Jennifer A. Mckinney, Eric Hoffmayer, Alistair D. M. Dove, Robert Hueter, Alessandro Ponzo, Gonzalo Araujo, Elson Aca, David David, Richard Rees, Alan Duncan, Christoph A. Rohner, Clare E. M. Prebble, Alex Hearn, David Acuna, Michael L. Berumen, Abraham Vázquez, Jonathan Green, Steffen S. Bach, Jennifer V. Schmidt, Stephen J. Beatty, David L. Morgan; Undersea Constellations: The Global Biology of an Endangered Marine Megavertebrate Further Informed through Citizen Science, BioScience, Volume 67, Issue 12, 1 December 2017, Pages 1029–1043, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix127

Background

Understanding the biology of marine organisms is particularly difficult; even for the largest fish in the sea. The whale shark (Rhincodon typus) is one of three known filter feeding species of shark and is found around the globe in tropical and temperate waters. Like other shark and ray species, whale sharks are slow to reproduce, mature late in life, and have extended life spans. These life history traits make them vulnerable to population declines; increasing the value of ecological studies. Whale sharks are known to gather or aggregate at different sites around the globe to feast on plankton blooms and mass fish spawns. Despite their size, most of our knowledge about whale shark aggregations has only been documented in the past decade. A large portion of the increase in available data is due to this species being the primary target of ecotourism and changes in the availability of underwater cameras. The rise in ecotourism and citizen science, data collection through the contributions or citizens, in recent years has become an invaluable tool for science providing data unavailable to small groups of researchers.

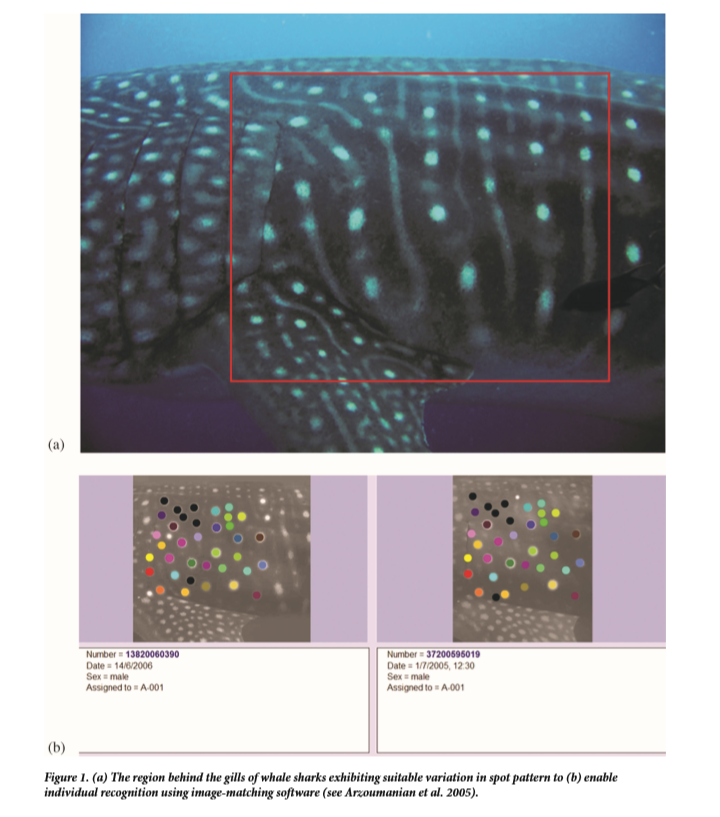

The increase in available photographs of whale sharks from ecotourism has led to the creation of the global database or ECOCEAN Whale Shark Photo-Identification Library http://www.whaleshark.org.au. Photo identification allows for global long-term identification studies of individuals and locations. Each whale shark has a unique pattern of spots located behind the gill slits that can be be analyzed using computer assisted pattern matching technology to identify old and new individuals. Each shark is assigned a specific code when added to the database using the abbreviation of the location first sighted and a number specific to that sighting location; for example, the fifty second shark seen in Belize would be identified as BZ-052. The photographer can also enter information on location, sex, and estimated total length (TL). Given the lack of data on whale sharks, collecting any information is incredibly valuable for understanding the distribution of this highly mobile species.

Study Goals

This study has two primary objectives that are relevant to understanding whale shark ecology including documenting the success of global monitoring of whale sharks and a review of the potential of the database moving forward. In order to achieve these objectives, the study looks at the database’s global and local sightings over an extended period, examines size and sex ratios, identifies sites with 20 or more resightings, and determines if resightings happen in multiple countries. The benefits and challenges of using citizen science for research are highlighted as well to address future directions.

Findings

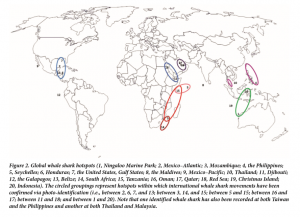

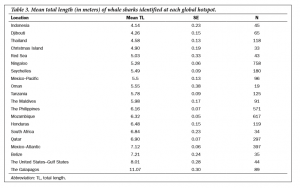

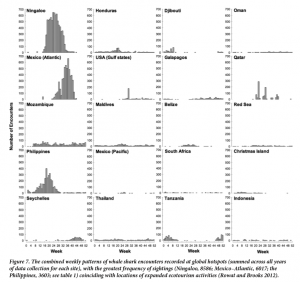

The study identified 20 priority sites that accounted for 99.14% of all whale shark encounters documented and led to the identification of almost 6000 individuals. The expansion of whale shark ecotourism in recent years is noted to have resulted in the number of “hotspots” increasing from 13 to 20 and more logged encounters. The majority of sites, have more male whale sharks present with only a few isolated locations such as the Galapagos, Red Sea, and Thailand sites having mostly female compositions. The largest individuals were documented at the Galapagos where the average size was over 35 feet and Indonesia had the smallest individuals at 13.5 feet on average. Most of the aggregations were formed by young individuals with a few being comprised of adults. Segregation in sharks is fairly common and has been documented in more than 10% of species that data is available for and these segregations are often driven by size, predation, food availability, reproduction, and social factors. While nursery use is common in sharks limited encounters with whale shark pups have been documented. This may be the result of pups covering a large area and not using nursery habitat.

At some locations whale sharks are present throughout the majority of the year. Certain individuals were photographed in consecutive or relatively close months at sites like the Maldives and Thailand. With the exception of these locations the majority of sites are seasonal or sightings only occurred during a period less than 6 months of the year. Interestingly, 35.7% of individuals returned to the same place two or more years in a row. Some sharks were even resighted annually in excess of 10+ years, with three whales sharks at Ningaloo Reef being resighted more than 20 consecutive years. The primary driver of aggregations in whale sharks is plankton density or food. Some individuals could even meet their daily nutritional requirements in several minutes when the prey was most abundant. It is hypothesized that these aggregations are opportunities to for sharks to meet their metabolic requirements with limited energy expenditure. Younger whale sharks seem to take advantage of these easy feeding opportunities to focus energy on rapid growth prior to becoming reproductive. There was little evidence of migrations between countries which is supported by recent genetics work.

Conclusions The application of citizen science to understanding the ecology of marine megafauna through ecotourism have shown to be an incredible asset for understanding global marine ecology. According to Andy Defrancesco, photographs provided by people on vacation, enjoying a casual snorkel, can now be used to fill in the gaps in biology of sharks that satellite tagging is not able to fill. By uploading their photos, people allow researchers access to long term information on whale shark global site fidelity, environmental and food driven movements. The growth of citizen science is providing a huge boost to the limited research groups studying these animals and provides some reassurance that everyone can contribute to the conservation of whale sharks