Hollensead, L.D., R.D. Grubbs, J.K. Carlson, and D.M. Bethea. 2018. Assessing residency time and habitat use of juvenile smalltooth sawfish using acoustic monitoring in a nursery habitat. Endangered Species Research 37:119-131 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00919

A few months ago, I wrote about sawfish research in Papua New Guinea, but if you live in the U.S. you can find sawfish much closer to home. The smalltooth sawfish (Pristis pectinata) once roamed throughout the Gulf of Mexico and along the East Coast, but now calls South Florida, particularly Everglades National Park, home.

Smalltooth Sawfish

Smalltooth sawfish are one of five sawfish species, a morphologically distinct group that actually are more closely related to rays than sharks. They are native to the United States where they were once found throughout coastal waters in the Gulf of Mexico and Western Atlantic Ocean. Records show that smalltooth sawfish occasionally ranged as far north as New York, but were much more common in the southeastern United States.

Smalltooth sawfish are considered critically endangered by the IUCN Red List and were protected under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 2003. Their population declines were mainly driven by bycatch mortality, accidental capture in fishing gear resulting in death, and habitat loss. Sawfish were also harvested extensively as trophies due to their unique rostrum, the long saw that extends from its face like a spikey nose. It is not unusual to see a sawfish rostrum hanging on the wall of a bar in Florida, just as you might expect to see a set of deer antlers on the wall of a bar in Wisconsin. Essentially, sawfish could not keep up with the harvest mortality and habitat loss. Now, one of the last remaining strongholds for young smalltooth sawfish is Everglades National Park in Florida.

What is a nursery area?

You might be wondering how a fish that lives in the ocean could lose its habitat when the ocean is so vast. Well, like many other coastal fish, smalltooth sawfish use nursery areas when they are first born. Nursery areas are often estuaries, with lots of available food and shallow waters for refuge from predators. Sharks and rays generally leave their nursery when they are larger than most of the predators they would encounter and are able to find food efficiently.

Coastal development can alter or remove the habitat that is essential for nurseries. In the case of smalltooth sawfish, they appear to prefer tidal flats along mangrove-lined coasts. Development in South Florida has lead to significant losses of mangrove-lined coasts, but Everglades National Park has helped to preserve a small portion of these mangroves. In this last remaining refuge, researchers at Florida State University and NOAA wanted to better understand the environmental factors that are important for sawfish habitat selection in the Everglades.

Research Methods

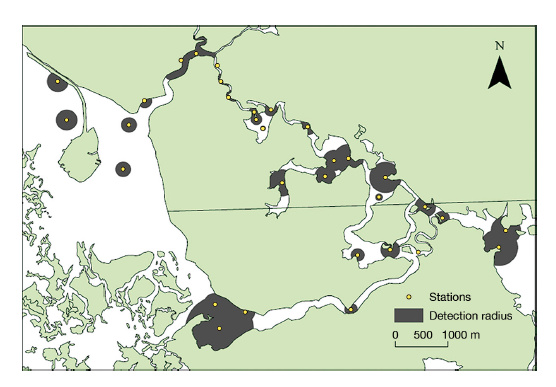

Dr. Lisa Hollensead and her collaborators set out to the northernmost portion of Everglades National Park to answer questions about how long young sawfish remained in this nursery area and what habitat characteristics were most important to them. To do this she used acoustic telemetry. I’ve explained how acoustic telemetry works in detail in a previous post, but briefly it involves a combination of tagged fish and anchored receivers. These receivers record the date, time, and tag number when a tagged fish swims by them, allowing researchers to track the movements of tagged individuals as they go from one receiver to the next.

Sawfish were caught using gillnets that were often set perpendicular to mangrove-lined coasts, spanning a range of depths from shallow to deep. Once caught, sawfish were carefully measured and tagged with an acoustic tag, which was attached to their dorsal fin.

To better understand what factors influenced where sawfish spent their time, Lisa quantified several different habitat factors near her anchored acoustic telemetry receivers. Along the shore closest to the receiver, she counted the number of red mangrove prop roots, as well as the tree limb overhang that extended out into the water. She also took sediment samples using a very high tech gadget, a garden trowel! You can check out what some of this fieldwork looked like in this video.

When asked about her experience conducting research in the Everglades, Dr. Hollensead said, “For me, being immersed in a wild and dynamic environment like the Everglades was humbling. For example, the tidal changes are so dramatic. Some portions of the study area were only accessible during certain times of the day and so I always had to be cognizant of the natural processes around me. As busy people, it’s sometimes very easy to get swept up in daily routines and become detached from the living world around us. The Everglades is a place that necessitates connection with your surroundings. My time in the Everglades was such a unique opportunity for personal growth and those lessons persist even now. Whether it’s looking at a perched bird while sitting in traffic or appreciating a dry space in a thunderstorm, the Everglades taught me the importance of association with the world around me.” The drawbacks? “The mosquitoes! I know I was just talking warm fuzzies about nature and all but my goodness I could have done without those swarming hordes!”

Research Findings

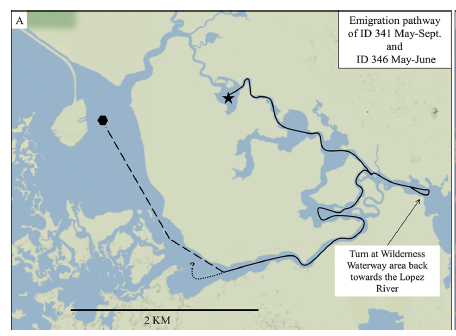

Dr. Hollensead and her colleagues captured and tagged 21 sawfish in Northern Everglades National Park. They heard from them in their acoustic receiver array for as many as 334 days. During this time, three sawfish that were tagged in Mud Bay, undertook an extensive journey down the Lopez River to different bays, including Chokoloskee Bay, where many other juveniles were tagged. Others left Mud Bay to enter nearby Cross Bay before leaving the acoustic array. Most of the sawfish that were tracked were tagged in Chokoloskee Bay. Unlike the Mud Bay sawfish, sawfish tagged in Chokoloskee Bay remained there for the entire length of the study, spending the winter in the area where they were tagged the previous spring. This was the first time that sawfish were documented to remain year-round in Everglades National Park, emphasizing the importance of the area to their continued survival!

Analyses of habitat use and sawfish movement found that sawfish moved quickly through creeks and rivers, but remained much longer in tidal bays. Researchers have several theories about why this is.

Because sawfish are mostly flat, like a stingray, as opposed to rounded like a shark, the best way that they can avoid predators is to move into shallow water where sharks cannot fit. The tidal bays likely provide better protection while still having sufficient food than a faster flowing, deeper river. It is unclear what drove the sawfish tagged in Mud Bay to leave, while those tagged in Chokoloskee Bay stayed there all year. It could be that they were following shifts in food availability, but further research is needed to better understand this. Analysis of other habitat factors showed that sawfish were more likely to be encountered in areas with more mangrove prop roots, and the sediment was almost exclusively fine silt. This makes sense since the sawfish are using the tangle of mangrove prop roots in shallow water as protection from predators. More roots could mean more protection.

While many questions remain, the importance of the Everglades and its many mangroves to sawfish is clear. When asked about the importance of Everglades National Park to sawfish conservation, Dr. Hollensead notes, “The Everglades National Park gives researchers a perspective of juvenile habitat use in a relatively pristine area. Generally, large portions of the Everglades are not developed (unlike much of the rest of south Florida) and the hydrology is not directly manipulated through anthropogenic influences, like dams, within the park. Results from habitat studies in the Everglades can be compared, almost like an experimental “control”, to habitat use results from more developed areas within their range. These comparisons can help scientists effectively implement management strategies for sawfish conservation.”

Further reading

If you’re interested in sawfish recovery, you can follow along with researchers on their Facebook page: US Sawfish Recovery.

If you see or accidentally catch a sawfish while fishing, please report your encounter to FWC and always follow safe handling and release guidelines.

I am currently a Marine Science and Technology Doctoral student at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. I use acoustic and satellite telemetry to study the spatial ecology of lemon, nurse, Caribbean reef, and tiger sharks in St. Croix to better understand habitat selection, residency, and connectivity between the protected areas and areas open to fishing. I am broadly interested in the intersection of marine animal movement, particularly elasmobranchs, with fisheries management. In my free time you can find me curled up with a good book and a cup of tea or outside exploring with Deacon, the goofiest Irish setter in Massachusetts.

What a fascinating article about an unusual endangered species through the lens of the marine biologist. Not being a scientist myself, I find scientific publications to be deep water over my head but this blog held my interest & brought the science to life! It’s cool that women scientists are out in the field handling sharks and writing recent publications about their work. Especially when the results are leading us to understand how to protect a rare species & it’s habitat. I hope we continue to preserve the Everglades from development.

I’m glad to hear you enjoyed the post, Charlotte. As a marine ecologist myself I always love hearing the stories behind how the field work gets done. Scientific publications are focused on the stepwise process of the research so you lose that human aspect. Talking with Dr. Hollensead for this post was great because I got to learn more about her victories and hardships in the field while studying this incredible species.

Way too many pictures of Lisa, and too few of sawfish, to be an interesting read. Seems more a promotional/publicity article for her personally than a report on science – save that stuff for Facebook, oceanbites should be about promotion of science and the value of research.

I appreciate your feedback. Part of what I value in the promotion of science is the promotion of diverse researchers. It is important to highlight women who do exceptional fieldwork as we are few and far between. We also can only share open access images or photos we have been given permission to share here on oceanbites due to copyright laws. There are very few pictures of sawfish that meet this criteria because they are so rare. I shared the photos that were available to me.

Hi Grace, I somewhat understand, but we have four exceptional field researchers (that include two women – one marine biologist, one astrophysicist) in our family, so the cadre is not as small as you may think. My point was that one picture would have gotten the “women in field science” message across nicely, three was an overkill. For fish pictures, next time try try Google Images and Wikipedia – you will find/would have found many images that note “This image is in the public domain because it contains materials that originally came from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, taken or made as part of an employee’s official duties”. Keep up the good work. Cheers.