Schoeman, R. P., Patterson-Abrolat, C., & Plön, S. (2020). A Global Review of Vessel Collisions With Marine Animals. Frontiers in Marine Science, 7, 292. doi:10.3389/fmars.2020.00292

If you are in the USA and see an injured or stranded marine animal, please contact your local stranding network.

A double-edged sword…

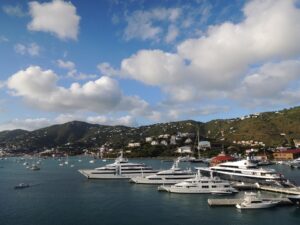

It’s a beautiful thing, hearing the blast of blow as a whale surfaces off the port side of a traditional wooden schooner. Or, in a more modern setting, watching dolphins leap from the foaming wake of a motorboat. These are picturesque moments, but unfortunately, there are sea life encounters that don’t end as peacefully. It’s been a reality of the last century and a half: as our global economy grows, our chances of encountering sea life increases. Recreational vessels line marinas (12 million boats were registered in the USA in 2019!), shipping fleets have expanded, and trade routes across the oceans are constantly busy. However, for the natural inhabitants of the blue waters, this expansion has brought noise, pollution, and the risk of collision.

You’re probably familiar with hazards like boats striking a surfacing whale, or propeller blades injuring slow-moving manatees. Encounters like these received a lot of attention in the late 20th century, especially when the animals involved were members of an endangered species. Endangered species aren’t the only ones affected though, as we see now in a large review about global vessel collisions by a team of researchers from South Africa.

How many species, why, and what can happen?

Since the 1890s, the number of large commercial vessels (ships with a gross tonnage capacity greater than 100) has increased almost nine-fold, from about 11,000 to over 94,000 worldwide. This alone has increased chances of vessel strikes on large marine mammals, like baleen whales—something the International Whaling Commission’s Ship Strike Working Group (SSWG) has actively documented since 2005. By 1980, it was recognized that smaller animals had the potential to get struck by boats, although no central database for recording hits was started. Reports from other studies examined in this global review, though, reveal over 75 species of marine life (from sea turtles to sturgeon to sharks) have been involved in collisions with large and small boats since then.

Strikes can also cause injury to ship crews or passengers. A freighter striking a small dolphin won’t likely jostle anyone aboard, but a smaller boat running into a larger whale can result in a jolt, causing crew to fall (sometimes overboard) or crash into fixed structures on board. Serious strikes can even damage the vessel’s hull or propeller, leading to further complications.

Are there ways to prevent these strikes?

Given the variety of vessels and animals involved when investigating global ship strikes, it’s impossible to find a “one-size-fits-all” solution—at least one where shipping still exists. Understanding the physiology and behaviors of the animals at risk of strikes is crucial—we’re dealing with organisms that often rest, forage, or socialize near the surface for various amounts of time. As a result, people have begun trying multiple approaches to reduce these encounters.

Placing trained observers aboard large cargo vessels is useful for limiting collisions with whales since they have a good vantage point from which to spot whale blow or flukes (provided the weather is decent). This isn’t feasible though for small vessels with few people aboard and a low profile close to the water’s surface.

Since many species involved in vessel strikes are known for communicating via sounds, auditory deterrents have been suggested to shoo them away from inbound ships. This received mixed results, with some species surfacing nearby not long after deterrent sounds were played. An added concern is that playing noises will only add to the existing cacophony from numerous engines, thereby stressing and disrupting more animals than the intended species.

The SSWG’s central database has provided the most information about whale strikes in terms of location, frequency, and timing, which has allowed conservation groups to pinpoint high-risk areas and notify mariners of increased chances of collisions. If a central database for smaller animal encounters and collision outcomes is created, we could send similar warnings based on a species’ abundance or presence in an area.

As with many animal-human interactions, we are faced with a large gap in our knowledge when it comes to solving the problem. Though we’re attempting to close the gap, it will take some time. Until then, making people aware of the issue at large is likely the best step we can take. So if you know someone with access to a boat, or are planning on going boating yourself, take a moment to learn about the species of fish, whale, dolphin, shark, or turtle that hang out in the local waters before turning the keys and heading out to sea.

I am a former PhD student from the University of Rhode Island, having discovered my love of teaching and informal science education in part through OceanBites! Since departing academia, I’ve focused on creating educational content for visitors at the New England Aquarium, Chincoteague Bay Field Station, and now the National Aquarium. I’ve also dabbled in co-creating a comedy/brainstorming podcast, ThunkTink, and enjoy getting lost in nature with my dogs.