In the Bible, the story of Noah’s Ark describes a storm so intense and so long that the earth is covered in water. All livings things perish, except for one crazy old man who built a massive boat on a tip from God and then took two of each animal to repopulate the Earth. Today, coral scientists are proposing their own “Noah’s Ark,” but this time the animals aren’t in danger of drowning. The relentless storm is climate change, and coral scientists watching the death of reefs around the globe want to be this generation’s version of Noah.

Save the reefs

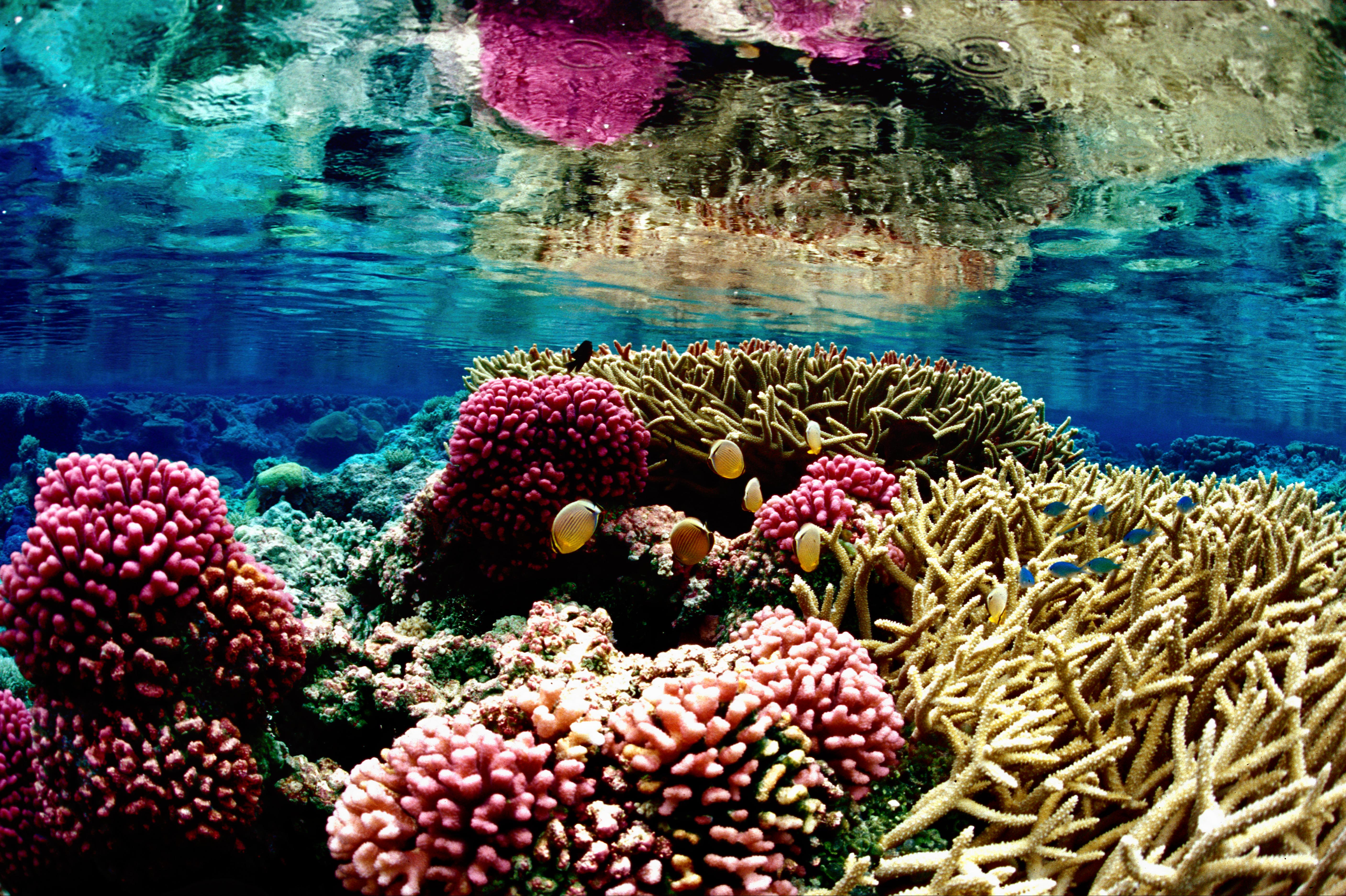

Reefs are beautiful underwater cities whose building blocks are small organisms that are part animal, part plant, and part mineral. The squishy coral animal, similar to a sea anemone, builds itself a hard outer shell made of calcium carbonate (essentially limestone). In addition, the coral accepts small algae cells (called zooxanthellae) into its tissue which photosynthesize and give nutrition to the coral. When corals get stressed, they will often expel these algae cells and leave the coral bone-white, a process called coral bleaching. As climate change and pollution have hit reefs around the globe, large bleaching events have become much more common. Bleaching in the Great Barrier Reef is just one of the more well-known examples.

These reefs are an ecological powerhouse, providing habitat and safety for a number of other species, many of which only exist in one part of the world. However, what many people don’t realize is that coral reefs are also an economic powerhouse. Globally, coral reefs are valued at roughly US$30 billion per year, and the livelihood of 600 million people rely on coral reefs, which support fisheries and drive local tourism, among other things. This means that saving coral reefs shouldn’t just be an environmental priority; it needs to be a priority from a human perspective as well.

The World Coral Conservancy

There have already been a number of efforts to save coral reefs where they are in the wild, notably through Marine Protected Areas and reef restoration. However, these approaches are all at the whims of what happens in nature. Years of progress could be set back by a massive heat wave, pollution, or the introduction of a new species, for example. In addition, Marine Protected Areas only cover about 10% of coral reefs.

As scientists studying coral reefs have watched their study areas die or degrade year by year, they have come up with another potential solution to help corals survive climate change. Like Noah’s Ark saved the animals during a global flood, why not have a figurative ark save corals during global warming? The researchers proposed that a network of aquariums and research institutions ban together to raise corals in captivity to preserve them for the future.

The World Coral Conservancy would have several goals for this Noah’s Ark project: 1) to house a wide range of coral colonies to preserve both genetic and species diversity with the goal of future reef restoration; 2) to develop solutions for keeping coral alive in the wild; 3) to create a database and supply of corals that can be used for science; 4) to use this research to potentially aid coral in evolving so that it can exist in a world shaped by climate change; and 5) to educate the public on corals.

Challenges

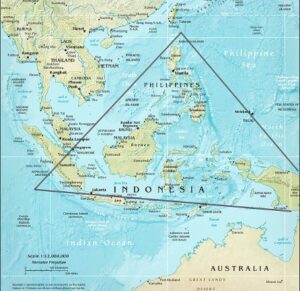

Choosing which corals get to enter the ark is one of the first major challenges to the project. As it stands, only around 15% of coral species have been successfully kept in captivity. Coral is a fragile animal – it requires just the right balance of temperature, nutrients, and light, and each species has its own particular needs. Going forward, scientists will have to decide if it is more important to select species based on their potential to adapt to climate change or for their role in the current ecosystem. Overall, the best approach is to gather a wide variety of corals from many places. This process can be made easier, however, by going somewhere like the Coral Triangle, an area between the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, and Indonesia, where 40% of the world’s species of coral can be found.

Still, scientists do need to be strategic about some species. They will have to gather a few species that show particular promise for dealing with climate change, like the corals that live in the warm Arabian Seas. They also noted that they would pay special attention to endemic species (those corals that only exist in one location). For example, the reefs in the Caribbean have around 62 different varieties of coral, but 43 of them exist only in the Caribbean.

One last thing the scientists need to be mindful of is ensuring that the corals coming out of the project aren’t only the species that are better suited for life in captivity. While part of the appeal of the project is having greater control over corals, this means that the corals could be subjected to a more limited range of environmental conditions. However, as coral research and technology has improved, it has also improved the scientists’ abilities to change conditions inside the aquarium and hopefully ensure the corals can adjust to natural conditions as well.

The past, present, and future

Projects like this are an attempt to bridge the past, present, and future together. Like Noah’s Ark protected the animals of the past during the storm so they could be with us in the future, the World Coral Conservancy hopes to do the same. With enough dedicated scientists, aquarists, and legislators, they may just have a chance.

I am a PhD student studying Biological Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography. My interests are in food webs, ecology, and the interaction of humans and the ocean, whether that is in the form of fishing, pollution, climate change, or simply how we view the ocean. I am currently researching the decline of cancer crabs and lobsters in the Narragansett Bay.