Powers et al. 2017. Movements and foraging habitats of great shearwaters Puffinus gravis in the Gulf of Maine. Marine Ecology Progress Series 574:211-226. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps12168

GPS technology: important for more than cell phones

Great Shearwaters are a common Atlantic seabird, yet chances are you haven’t had the opportunity to see one. These birds spend almost the entirety of their lives at sea, only coming to shore to breed on remote islands in the Southern Hemisphere.

Their pelagic, or open ocean, habits make this bird tough to study; in the past, scientists relied on observations made aboard ships to figure out where these birds were hanging out across the Atlantic basin. Yet shipboard observations are only a snapshot, indicating a bird’s one-time location; this type of data doesn’t provide any information about the bird’s history, current activities, or more general habitat preferences. Enter GPS technology, courtesy of modern satellite systems; not only do satellite location systems provide you with ready directions on your cell phone, but these systems also provide scientists an additional way to study the whereabouts of tough-to-study creatures like seabirds.

The study: “playing tag” with seabirds

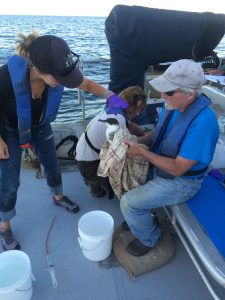

Kevin Powers and other researchers from across the northeast Atlantic leveraged tiny satellite tags, referred to as platform terminal transmitters or “ptts”, to figure out where Great Shearwaters are spending their time while in the Gulf of Maine region. The team tagged birds at three open water locations in the region over summer and fall months, close to Maine, Massachusetts, and within the Bay of Fundy in Canada. The birds were lured close to small boats using bait, and then were nabbed using handled landing nets. The tiny tags were attached to the birds with a variable combination of special glue, stitching, and tape. The tags were less than 3% of the birds’ total body weight, to ensure the tags didn’t interfere with or weigh down the bird. The researchers also collected data about the birds age, along with some feather and blood samples for further diet analyses. Once the bird was released, the tags pinged back the position of the bird at variable time intervals over the course of the following few months; most tags stayed attached for a period of 60-132 days, after which the tags would fall off or the battery would die.

So much more than just a location…

The tags revealed that Great Shearwaters are akin to ultra-marathoners; the birds traveled an average of 515 km per day. The tags also provided a wealth of information about what ocean conditions are attractive to seabirds.

The researchers found readily available oceanographic data (like temperature, depth, slope of the bottom) describing the Gulf of Maine from government agencies and satellite data repositories, including NOAA and NASA. They then overlaid the birds’ location data over these environmental data to figure out what characteristics were important draws, or what conditions/environments the birds liked to spend time in. The birds liked to hang out in “rim” environments, or those regions of the Gulf of Maine that border deeper basin waters; overall the birds preferred shallower water. They also found that Great Shearwaters tagged in different locations were differentially drawn to key oceanographic variables. For example, birds that were tagged off the coast of Massachusetts were positively correlated to sea surface temperatures, meaning the birds spent more time in warmer areas, while birds tagged in the Bay of Fundy and Maine preferred to aggregate in areas of cooler sea surface temperature. This means the birds are flexible in terms of habitat use and what environmental features are attractive to them based on unique and variable local conditions.

Serious implications of a simple study

Satellite tags are expensive, so descriptive tagging data like this is pricey and, more often than not, rather rare and limited. As a result, this particular dataset is remarkable in its range; a whopping 66 tags were put on birds over a number of years, meaning this is more than just a snapshot of a few birds in single year.

Additionally, this tagging data is important for regional and global management of seabirds. The Gulf of Maine is warming faster than most other areas on the planet, experiencing an approximately 1.5C increase in temperature thus far. Understanding where birds are hanging out and feeding in this rapidly changing system is key, as we can better protect Gulf of Maine and global seabird populations from the impacts of climate change if we work to protect their food sources and preferred habitats…we need to have this sort of descriptive “where” information before protection measures can even be dreamed up.

As well, the Gulf of Maine is home to tremendous commercial and recreational fishing. Seabirds are prone to being caught as bycatch in fishing nets, meaning the birds get tangled in nets or hooked on lines intended to catch other creatures and drown. Tagging data revealing where the birds spend most of their time can help inform fisheries management and bycatch regulation, by allowing fishery and habitat managers to keep certain areas off limits or recommend the use of specific gear that is less dangerous for birds in areas known to be bird hotspots.

Overall, although the question of where a creature lives is seemingly simple, we still don’t know a lot regarding the habitat preferences of even common marine animals like Great Shearwaters; tagging studies like these go a long way to inform management and understanding of a particular species and the greater ocean environment where they reside.

I am a third year PhD student at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography in the Lohmann Lab. My current research interests include environmental chemistry, water quality, as well as coastal and seabird ecology. When not in the lab, I enjoy diving, surfing, and hanging out with my dog Gypsy.