Source: Chen, C.-T. A.; Lui, H.-K.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Yanagi, T.; Kosugi, N.; Ishii, M.; Gong, G.-C. Deep oceans may acidify faster than anticipated due to global warming, Nature Climate Change 2017, 7 (12), 890-894. DOI:10.1038/s41558-017-0003-y

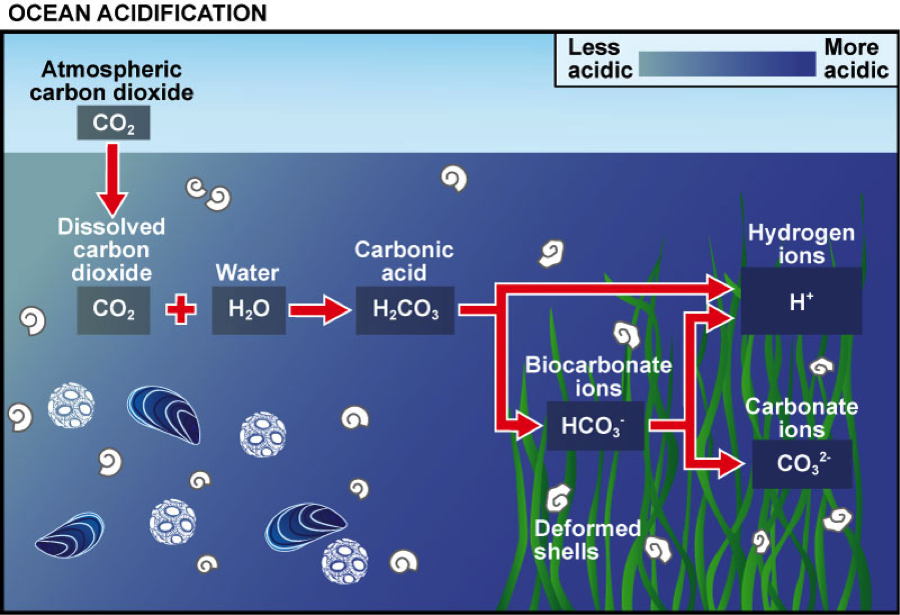

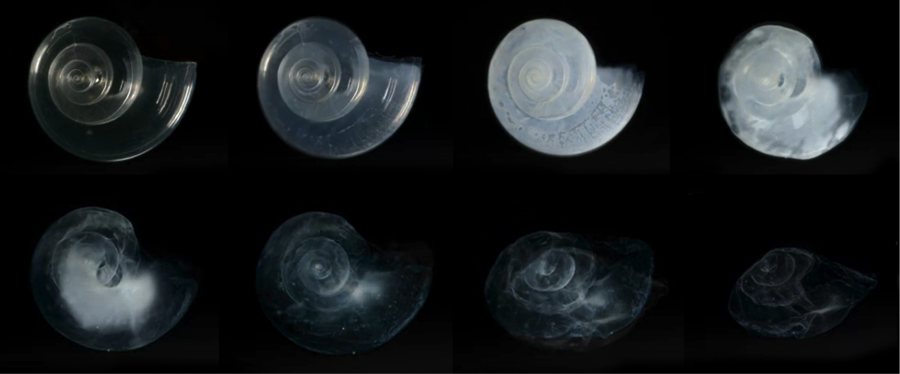

You may have heard about ocean acidification; it’s a high visibility issue that has helped raise awareness that human activity can have profound and detrimental effects on the ocean. A fraction of the carbon dioxide (CO2) we pump into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels to power our lives gets dissolved into seawater, breaking into several different molecules (Figure 1). One of the molecules produced is the hydrogen ion, or H+, which makes the water slightly more acidic. This change in chemistry can be to the detriment of species including coral-reef-building organisms and calcium-containing phytoplankton, that incorporate another molecule, calcium carbonate, into their skeletons (Figure 2). (The added hydrogen ions cause calcium carbonate, which often make up the shells of such species, to dissolve.) The current rates of ocean acidification at the sea surface are the highest our planet has ever experienced.

The researchers’ hypothesis follows a simple and logical line of reasoning, but one that first requires an explanation of some basic ocean biogeochemistry.

In the uppermost part of the ocean, the region touched by sunlight, phytoplankton and other small organisms are going through their cycles of life and death. When an organism (perhaps as small as phytoplankton or as large as a shark) dies, its body sinks. As it sinks away from the sunlight, other organisms decompose the organic matter of its body. This decomposition can be summarized as: organic matter (some combination of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and phosphorous atoms) + oxygen + carbon dioxide + water + nutrients. So when the sinking matter decomposes, oxygen is consumed and carbon dioxide is produced.

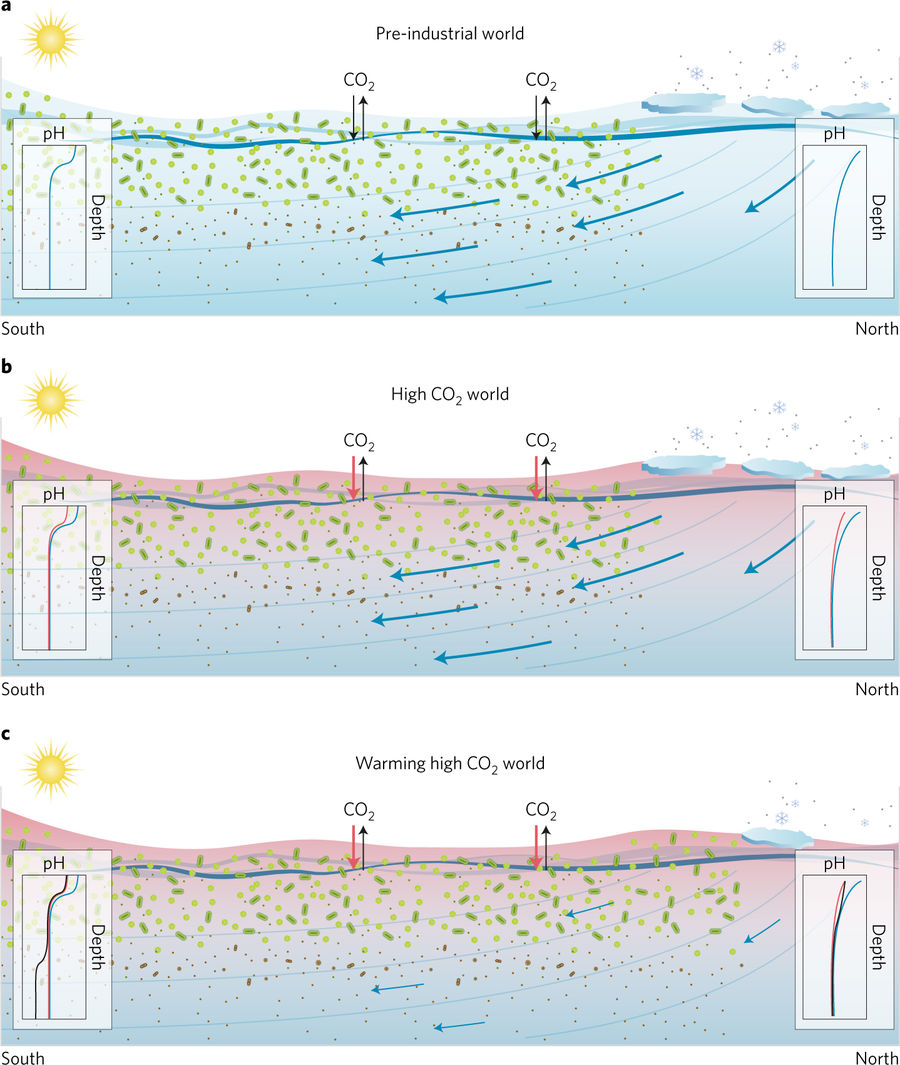

In the preindustrial world, the deep ocean achieved a natural balance of oxygenated water coming in and oxygen-depleted water going out thanks to its undisturbed ocean circulation patterns. But as we warm the planet by emitting carbon dioxide—a heat trapping gas—by burning fossil fuels, ocean circulation patterns are predicted to change.

Water in the ocean is separated based on density: layers of colder denser water rests on the bottom, and layers of warmer, less dense water sits on top. Water doesn’t mix very well across these density gradients; bring to mind the frustration of trying to get your oil and vinegar salad dressing to stay mixed. As we heat the atmosphere, the water at the surface will continue to warm, creating an even more drastic temperature (and therefore density) gradient, making the ocean more stratified. An increase in ocean stratification will weaken the movement, or circulation, of water in the ocean. As a result, less water is circulated into and out of the deep ocean, and the “ventilation” of the deep ocean with oxygenated water is diminished.

In the preindustrial deep ocean, the carbon dioxide released through the decomposition of organic matter would be consistently circulated out of the depths (Figure 3, panel a). But if ocean circulation weakens, then this carbon dioxide is expected to build up in the deep (Figure 3, panel c). And following the same seawater carbon chemistry reactions occurring at the surface, this built-up CO2 will in part dissociate into H+ molecules, raising the acidity of the deep waters.

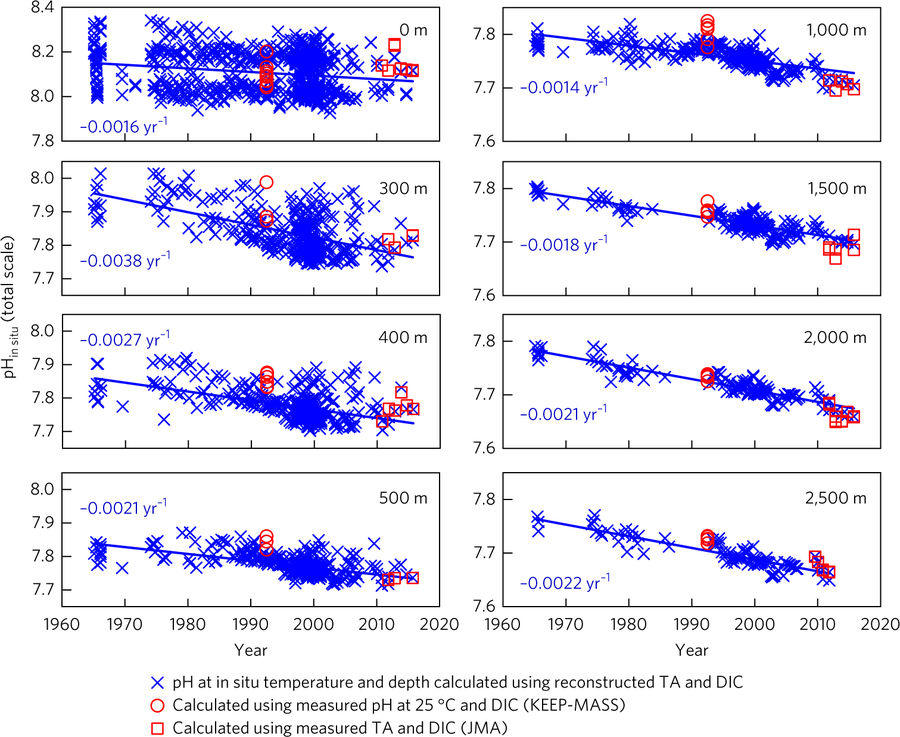

Studying trends concerning the entire global ocean isn’t easy given how vast (both in width and depth) the subject and relatively sparse the data. To overcome these limitations, the group of researchers focused on the Sea of Japan, which has often been used in studies as “miniature” ocean. The Sea of Japan is fairly isolated from the surrounding ocean (Figure 4) and also has its own water circulation pattern that is similar to the global ocean circulation. For their study, Chen and the researchers used a 50-year record of oxygen and pH (a measure of acidity, where lower pH translates to a higher acidity) data taken at a handful of depths.

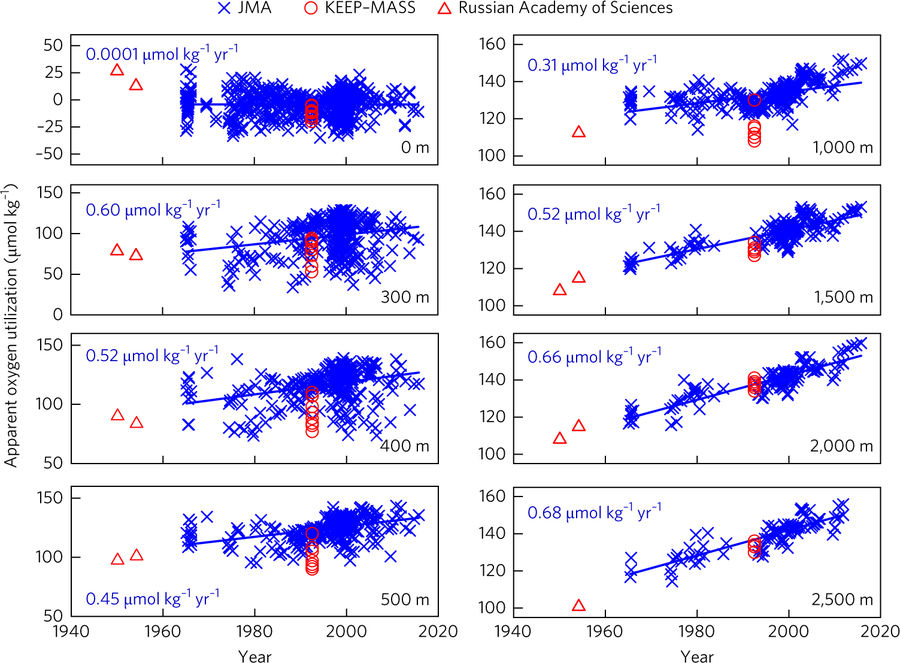

You might be asking why they chose to inspect oxygen levels over time in addition to pH. They did this in order to get a measurement called apparent oxygen utilization (AOU), or how much oxygen has been consumed relative to how much oxygen the water can hold. Remember that oxygen gets used up in decomposition reactions. So if in the deep ocean, oxygen was being used up in the CO2 producing decomposition reactions, lowering the oxygen level over time, it likely means that water rich in oxygen coming from the sea surface wasn’t being circulated to the deep. If the researchers’ hypothesis holds that decreased circulation was causing the water to acidify, then the data should show a clear increase in AOU along with the decrease in pH.

The data from the Sea of Japan yielded exactly what the researchers suspected. It clearly shows that both the acidity and AOU increased in the basin over the past 50 years (Figures 5 and 6, respectively). In fact, the data indicated that the rate of acidification occurring near the bottom of the Sea of Japan is 27% greater than the rate of acidification at the surface. This figure is much larger than estimates from prior studies, suggesting that deep ocean acidification is a much bigger issue than previously imagined. The numbers put out in this paper alert us to the fact that human-caused changes in the ocean might be far more profound than we expected.

Chen and his colleagues recognize that the Sea of Japan isn’t the perfect model for the global ocean. The circulation patterns in the global ocean are much more complex, and the length of time it takes for water to circulate is much longer. But their study provides evidence that the deep ocean may become more acidic as the ocean warms.

The impacts of deep ocean acidification have not yet been thoroughly investigated, but any sudden change in local chemistry certainly has the potential to stress local ecosystems, if not influence the chemistry of the greater ocean. It’s important to know the scope and reach of the impact that human activity has on our planet, whether it’s to prevent future harm or to mitigate harm we’ve already caused but have only just discovered. The study conducted by Chen and his colleagues expands the view of the effects of human activity on seawater chemistry, and gives us a peek into what the future ocean might look like if we don’t change our ways.

Julia is a PhD student at Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California. Her focus is on biogeochemistry, which, as the name suggests, centers on the combined effects of biological, geological and chemical processes on the earth system. She is advised by Dr. Ralph Keeling and is modeling the global carbon cycle to better understand how much carbon dioxide ends up in the atmosphere. When not at her computer writing code, Julia can usually be found reading and/or thinking about food.

very good explanation of the info, it helped me a lot! Thanks

Thank you for this very insightful article. I live in Hawaii and have always been an ocean girl at heart. Recently I was on the north shore of Oahu at sharks cove eating at a little truck stand across from the ocean. It was quite heart breaking because as I was looking across the way their was so much trash. Empty plate lunches, sunscreen bottles and straws. For my Hawaiian scholarship we are required to do a service project and as the ocean is a love of mine I’ve organized a group of people to do a beach clean up. Hopefully we can keep it going on regular basis. Thankyou for all you do and all your research in efforts to help protect the ocean and the life in it. I will be sharing this to our FB page. Mahalo