Whitehead H, Smith TD and Rendell L. 2021. Adaptation of sperm whales to open-boat whalers: rapid social learning on a large scale? Biology Letters 172021003020210030 http://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2021.0030

Understanding whales of the past

In a recent study published in the journal Biology Letters, researchers present evidence that sperm whales learned ways to avoid 19th century whalers, and these avoidance strategies then spread through the population as they learned from each other.

But how can we possibly know what whale behavior was like in the 1800s?

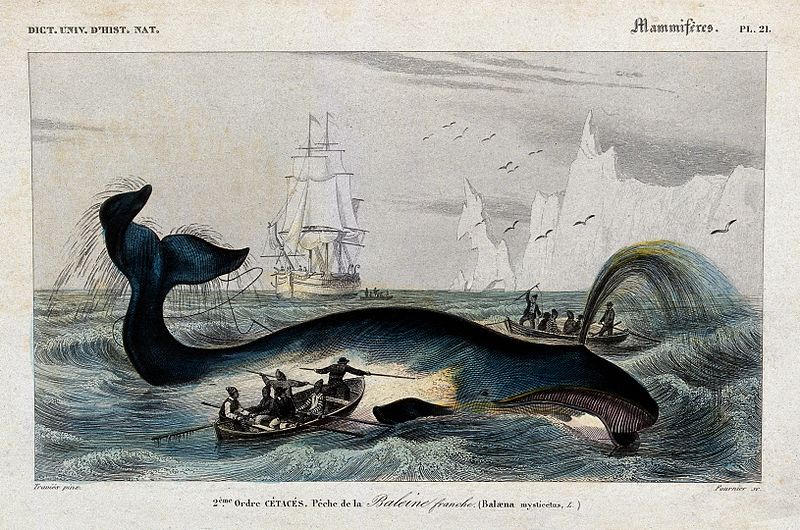

Many whalers kept detailed log books, describing what types of whales they saw and when and where they sighted and successfully (or unsuccessfully) harpooned whales. A number of these logbooks have even now been digitized, so people all over the world can access whaling history.

Soon after American whaling began in the North Pacific in the 19th century, the number of sperm whales harpooned in the region decreased by 58%. Some historians have suggested that this rapid decrease may have been the result of whales learning from each other, a phenomenon called social learning, to avoid whalers.

The culture of sperm whales

Social learning of avoidance strategies would not be all that surprising, given what we know about the complex cultural lives of sperm whales. These whales gather in family groups, called clans, which each have their own dialects and intricate social relationships. It seems plausible that these clans could discover strategies for surviving encounters with whalers and share these strategies between clans.

But even knowing about modern sperm whale culture and historical whaling logs does not provide a full picture of 18th century whale behavior, nor does it provide sufficient evidence to say that social learning allowed sperm whales to adapt to whaling.

Modeling the possibilities

To formally test the hypothesis that social learning explains the rapid decrease in whaling success in the North Pacific, researchers constructed mathematical models of different possible scenarios and tested how well these models fit the actual whaling data reported in the logbooks. These models reflect the social learning hypothesis and three alternative hypotheses for why the number of whales killed decreased after the start of whaling: 1) whalers were more skilled than later whalers, 2) the first catches were of particularly vulnerable individuals, and 3) individual whales learned to avoid whalers from their own experience.

Each of these models provided estimates of what the number of whales caught per day would have looked like over the 25 years after whaling began in the North Pacific. These estimates can then be compared to the actual number of whales caught over time to decide which hypothesis is the most likely to have occurred.

Of the four modeled scenarios, the social learning hypothesis consistently fit the logbook data better than any of the other hypotheses, leading the authors to suggest that whaling data provides evidence of rapid social learning of whaler avoidance over a large region.

Adapting to change

Before whaling, sperm whales didn’t have many predators. They only needed defensive behaviors for encounters with killer whales, but these defensive strategies were probably not effective against whalers. For example, sperm whales often fight back against killer whales as a group at the surface; however, this strategy would make them an easier target for whalers. Over time, they may have learned strategies like diving deep when they encountered whalers, avoiding whaling boats all together, or finding other ways to attack whalers.

By using innovative methods to understand whales of the past, research can provide us with a better understanding of how whale populations have changed over time, as well as how they may adapt to continued changes in the future.

I am a PhD candidate at Syracuse University studying marine mammal communication. My research focuses on analyzing underwater recordings of whale calls in order to better understand whale behavior. I’m also interested in education, outreach, and science communication. When I’m not listening to whale sounds, you can find me curled up with a good book or complaining about how much it snows in Syracuse.