Edgeloe JM, Severn-Ellis AA,Bayer PE, Mehravi S, Breed MF, Krauss SL,Batley J, Kendrick GA, Sinclair EA. 2022 Extensive polyploid clonality was a successfulstrategy for seagrass to expand into a newlysubmerged environment.Proc. R. Soc. B20220538.https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.0538

**********

A seagrass plant that clones itself?

If I told you that the world’s largest plant is a seagrass plant that clones itself, would you believe me? The world’s largest plant, for a while, was the flower Rafflesia arnoldii, also known as the Stinking Corpse Lily. It has been noted for producing the largest individual flower on Earth, native to the rainforests of Sumatra and Borneo. And yet, who knew that we could find something even crazier: a 4,500-year old seagrass plant that, indeed, clones itself.

Image source: Harvard Magazine 2017

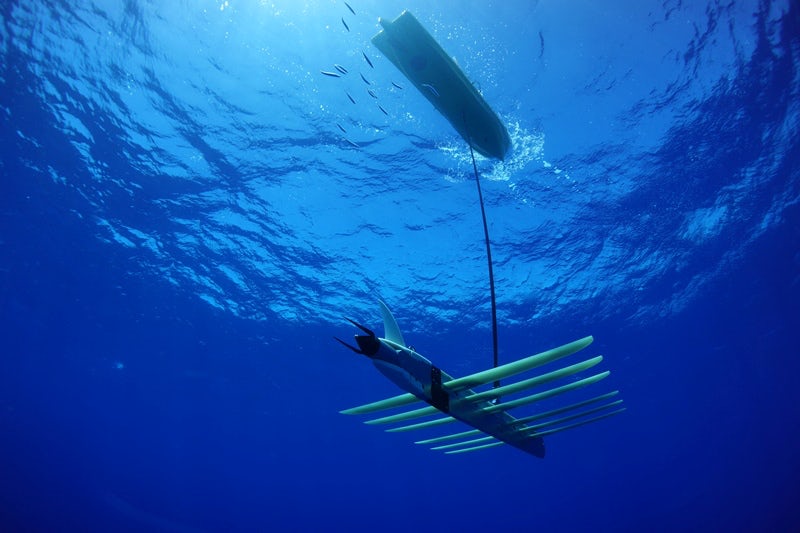

As part of a survey, researchers collected samples from ten seagrass meadows across Western Australia’s Shark Bay, about 500 miles north of Perth, and studied 18,000 genetic markers to test how many different plants grew in the area.

Poseidon’s ribbon weed.

Seagrasses are a polyphyletic group which evolved through at least three independent ‘return to the sea’ events in the early Cretaceous. Seagrasses now inhabit marine coastlines and estuaries globally, except for Antarctica. They reproduce sexually through flowering and seed production, and clonally through vegetative growth via horizontal rhizome extension. Most seagrass species have broad geographical distributions with wide-ranging levels of genetic diversity, and some meadows have expansive, long-lived clones.

The plant, called Poseidon’s ribbon weed or Posidonia australis, is 4,500 years old. The results “blew us away: it was all one plant,” the authors write in The Conversation. “One single plant has expanded over a stretch of [112 miles].” The authors hypothesized that after Shark Bay was first flooded about 8,500 years ago, the seagrass originated a few thousand years later, growing into newly submerged areas nearby.

This plant is the largest known example of a clone in any environment on Earth and arguably the world’s largest living organism, co-author Elizabeth Sinclair from the University of Western Australia has said.

The history of seagrass recolonization.

Seagrasses recolonized the Australian Continental shelf with rising sea levels following the Last Glacial Maximum, and this included the marine transgression at Shark Bay. A period of rapid sea-level rise during the Holocene created extensive inundation and new habitat for benthic marine species. This included temperate seagrasses. Expanding seagrass meadows thus trap sediments, and this ultimately controls environmental gradients through the development of the Faure Sill and Wooramel Seagrass Bank. This creates extreme environments for seagrasses (and other marine species) to inhabit.

Poseidon’s Genetics.

In addition to its gigantic size, the plant’s genetics are also unusual. Most seagrasses inherit half of each parent’s genome, but the seagrass in Shark Bay carries the entire genome of each parent, a condition known as polyploidy. On top of that, the seagrass also appears to be a hybrid of two species. Notably, this kind of clonal propagation has made for even older organisms, like a turtle grass estimated to be about 6000 years old.

The metahaline (the culturing of animals in the water salinity ranges from 36-40%) and hypersaline (an aquatic environment that is saltier than typical seawater) shallow waters within Shark Bay now experience temporal and spatial fluctuations in temperature and salinity in phosphorus-limited waters. Here, Dr. Sinclair and team use a genotype-by-sequencing approach to (i) assess population genetic diversity and structure of P. australis across the environmental gradient within Shark Bay and (ii) use karyotyping (the process of detecting chromosomal abnormalities) and flow cytometry (the measurement of properties of cells) to determine the presence of polyploidy (the condition in which a normally diploid cell or organism acquires one or more additional sets of chromosomes).

The perfect storm…. or, heatwave?

Shark Bay is situated at the temperate–tropical interface, meaning it is exposed to temperate and tropical extremes of climate change and extreme weather events, such as marine heat-waves and cyclones. The west coast of Australia was exposed to an unprecedented heatwave in the summer of 2010-2011, which impacted both terrestrial and marine ecosystems, with sea surface temperatures greater than 3°C above long-term averages in Shark Bay. Most areal loss of seagrass meadows was associated with Amphibolis antarctica, where extensive defoliation resulted in local extinction of meadows.

A total estimated area of 1,310 km^2 of dense seagrass meadows disappeared between 2010 and 2014 and consisted almost entirely of temperate species. The approximately 200 km^2 of Posidonia australis meadows were also impacted, although some natural recovery has occurred where shoot densities have now returned to pre-heatwave levels in some locations.

Concluding Thoughts

The proposed superiority of this polyploid clone over diploid P. australis suggests to Dr. Sinclair and team that vegetative material from the polyploid is best for the restoration of degraded meadows in Shark Bay. Exactly how the polyploid clone varies its response to local environmental conditions is unknown and the subject of further research, but its relative abundance suggests that it has evolved a resilience to variable and often extreme conditions that enable it to persist now and into the future.

Krti is interested in the transmission dynamics of environmental diseases as they relate to climate and anthropogenic stressors. As a Fulbright Scholar, Krti conducted analyses on the responses of dengue fever to climatic stressors off the coast of the Bay of Bengal, in India. Currently, Krti works with Stanford University to understand the role of schistosomiasis in environmental reservoirs, and leads the pursuit of a computational-based based analysis of eelgrass wasting disease dynamics. At Stanford, Krti serves as one of the few trans-disciplinary experts for planetary health topics, via machine learning and computer vision, data science, environmental policy, and science communication. As a STEM innovator and a first-generation woman of color, Krti is proud to be a writer for Oceanbites!