Sumich JL. Why Baja? A bioenergetic model for comparing metabolic rates and thermoregulatory costs of gray whale calves (Eschrichtius robustus). Mar Mam Sci. 2021;1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/mms.12778

An epic migration

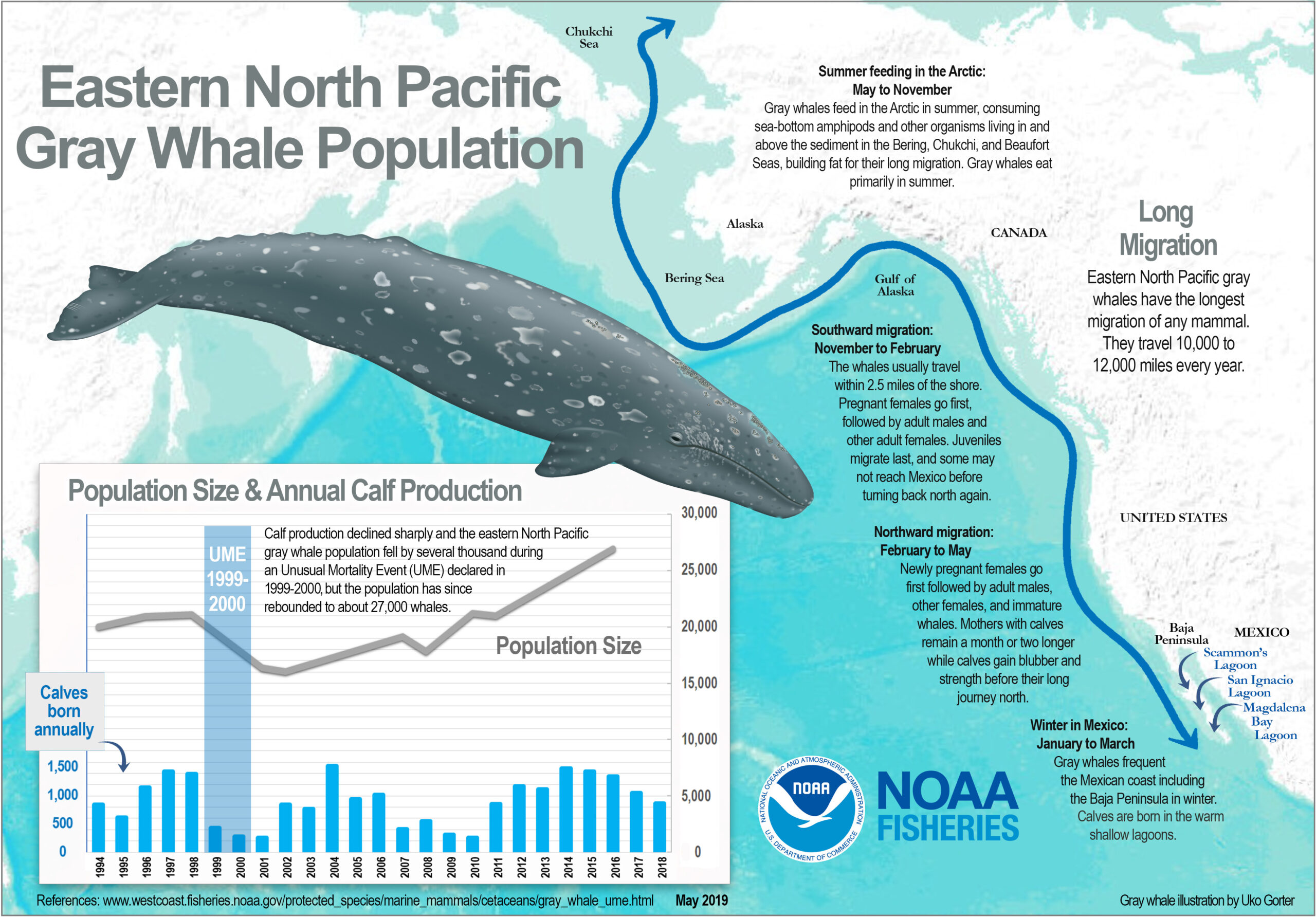

Gray whales undertake one of the longest migrations of any animal on earth. These giants travel a whopping 12,000 miles round trip, from the icy waters of the Arctic to the warm lagoons of Baja California. Like other baleen whales, gray whales spend summers feeding in productive northern waters and then fast during winter in their equatorial breeding grounds.

But why swim 12,000 miles? What makes such a perilous journey worthwhile? Scientists have been asking this question about baleen whale migration for years, and there still is no clear answer.

Subtropical paradise

Gray whales and other baleen whales use the warm, clear waters of their southern habitats for mating and calving. Female gray whales give birth in the calm lagoons of Baja California, and use these nursery grounds to raise their calves during winter. Some of the hypotheses as to why baleen whales migrate to low-latitudes to fast throughout the winter include calf thermoregulation and predator evasion.

Young calves have thinner blubber layers than older whales, and it’s possible they have a more difficult time regulating their body temperature in cooler water. Warmer waters at low latitudes would then provide the advantage of keeping calves warm.

Low latitude habitats could also be beneficial because there are fewer killer whales (orcas) present. Bigg’s killer whales (also known as transients) are the primary predator of gray whales, and killer whale attacks on gray whale calves are common along the US west coast. While gray whales range from the Arctic to Mexico, mammal-eating killer whales are usually only found as far south as Southern California. Gray whales may have evolved to give birth and nurse their young in sheltered bays further south in order to avoid mammal-eating killer whales which roam to the north.

To test whether the warm waters of Baja California would be beneficial to a calf’s thermoregulation, marine biologist James Sumich constructed a model of the heat losses of gray whale calves. This model was developed using a number of equations derived from tests of gray whale biology in the field. By summarizing factors that contribute to heat loss as well as calculations of calf metabolic rate, this model can provide insight into which habitats are suitable for gray whale calves. Sumich used previous reports of calf size, growth, oxygen uptake, overall unregulated heat losses, and other characteristics related to thermoregulation to construct the model.

Surprisingly, he found that gray whale calves would be capable of regulating their body temperature even in cooler mid-latitude and even northern waters. Mothers and calves often spend a longer period of time on the breeding grounds than other gray whales, but based on calf growth and thermoregulatory ability, the pairs could reasonably travel north much sooner to resume feeding.

Avoiding killer whales

The winter lagoons where gray whales spend a few months each year thus do not seem to provide any substantial thermal benefit to calves, suggesting that calf thermoregulation is not the reason for such long migrations to southern breeding grounds. Instead, Sumich suggests that predator evasion is more likely. The killer whales which feed on gray whale calves also target seals and sea lions as a primary food source, leading to larger congregations of orcas further north where this prey source is more abundant. Few killer whales are seen around the southern lagoons where gray whale calves are nursed, which may be the reason pregnant females continue to swim 12,000 miles to return to these sites year after year.

The killer whale predation hypothesis still needs further testing, especially as it might apply to other baleen whales like humpbacks or right whales. There may also be other characteristics of low latitude winter habitats which we have yet to investigate that make them the target of migrating whales. With continued observations and innovative experiments, we are slowly uncovering the mysteries of these ocean giants.

I am a PhD candidate at Syracuse University studying marine mammal communication. My research focuses on analyzing underwater recordings of whale calls in order to better understand whale behavior. I’m also interested in education, outreach, and science communication. When I’m not listening to whale sounds, you can find me curled up with a good book or complaining about how much it snows in Syracuse.