Last week I attended a development workshop titled ‘Strategic Persuasion for Meetings & Negotiations’ designed and hosted by Nancy Houfek while I was in California for a science meeting.

Such a workshop is invaluable to scientists because, for the most part, it is not a skill we are specifically taught, or tasked with. It was a common sentiment among workshop attendees that the prospect of even getting a job at certain institutions leaves us so elated, we are left with little desire to negotiate the salary. I found the workshop really informative and I wanted to share some of the experience and take away messages with you.

Houfek opened the workshop by having each participant introduce themselves and describe their research in one sentence. As we went around the room, she took notes that she continued to reference for the duration of the workshop. She did not reveal what was transcribed, but I suspect it included notes about our body language, eye contact, and projection during the introductions, as those are important factors in negotiating because they help us establish an energic connection by bringing our ‘best self’ to the role.

To make the point that negotiating is an activity that we do on a frequent basis, and that we may possess more skills than we realized, Houfek had each workshop participant identify a recent or upcoming negotiation in which we were involved, and what we felt our challenges and strengths were in that negotiation. In each of our examples, she was able to reiterate that every negotiation has a series of elements: 1) parties involved, 2) issue(s) at hand, 3) positions of each party, 4) interests of each party, 5) differences and agreements between the parties with respect to position and interest, and 6) expectations of give and take.

As Houfek moved into how to effectively negotiate, she started with the basic communication skills. In what will likely be an exercise that I never forget, Houfek had us pair off with someone we hadn’t met. She gave each pair a tennis ball to represent information that each pair wanted to communicate between each other. First, she had us toss the ball with our partner. Then, instead of just tossing the ball, she instructed us to silently think ‘I am passing you the ball. Are you ready? Here it comes.’ as we looked at our partner. The group noticed that when we were consciously thinking about tossing the ball, the transfer of information was slower, but in the end, we achieved the same outcome. The take-away from these first two exercises, was that in a negotiation, it is of utmost important that information is delivered in single, deliberate exchanges. The third instruction Houfek gave was to toss the ball with a different style each turn to make the point that information can be delivered in different ways, some more effective than others, and if one way is not working, try something new.

In the workshop, we learned a plethora of negotiating strategies. Three of the most emphasized were: 1) knowing your purpose, 2) not personalizing the situation, and 3) Taking a step back to garner the big picture and discern the behavior and tactics with the person(s) with which you are negotiating. At the start of a negotiation, be able to fill in the phrase ‘I want to find a way to get (name/pronoun) to do __(action)__’ because it enables you to identify the tactics to use in the negotiation.

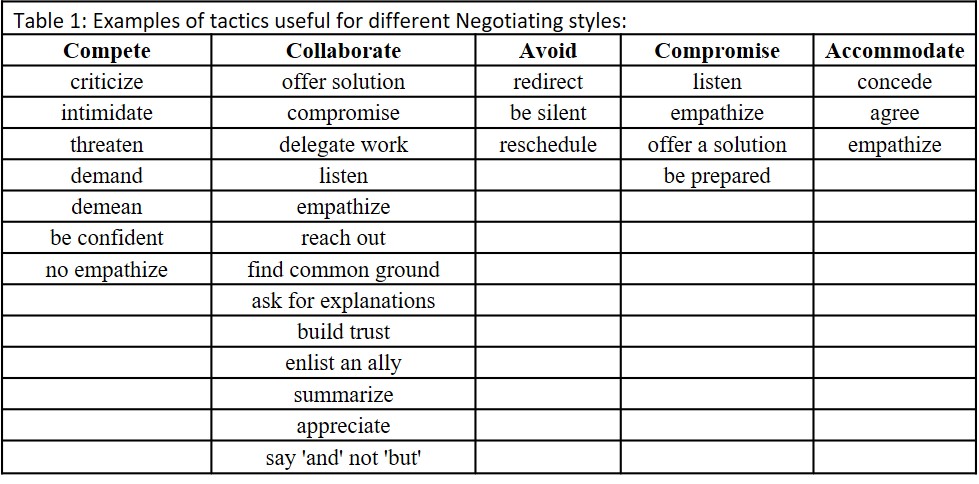

Negotiating tactics are plentiful, and depending on the type of negotiation you are in, some tactics are more appropriate than others. Five types of negotiations are: competition, avoidance, accommodation, collaboration, and compromise. The type of negotiation is a function of the levels of assertiveness and cooperation between the parties. In time-sensitive negotiations, a competitive style that results in quick action with no room for negotiations is appropriate, whereas if you were trying to build social capital, accommodation may be a better style, or if you are limited by information, avoidance may be the best route. Whatever the negotiating style, there are tactics that should be used (Table 1).

Negotiating tactics are plentiful, and depending on the type of negotiation you are in, some tactics are more appropriate than others. Five types of negotiations are: competition, avoidance, accommodation, collaboration, and compromise. The type of negotiation is a function of the levels of assertiveness and cooperation between the parties. In time-sensitive negotiations, a competitive style that results in quick action with no room for negotiations is appropriate, whereas if you were trying to build social capital, accommodation may be a better style, or if you are limited by information, avoidance may be the best route. Whatever the negotiating style, there are tactics that should be used (Table 1).

As important as the identifying your purpose and applying the correct tactics based on your strategy, is your physically preparedness. When you show up to negotiate you want your physical presence to be approachable, confident, ready to listen, and ready to present, without being arrogant. Houfek reminded us that it is often easiest to stay alert when we are at the front of our chairs, with feet flat on the floor, open hands on the table, shoulders dropped, and spine elongated. This position will make you present and available. If you disagree with the person your negotiating, you can communicate that with your body language by simply leaning back. A strong, upright position also empowers you to talk in a clear, projecting voice so that your words are heard correctly and no sentence is left trailing off into mumbles, ultimately weakening your ability to negotiate. Remember to warm up your body and your voice so that you should up to the role with total physical preparedness.

Before entering a negotiation, identify the range of comprises with which you are willing to agree too, and a list of possible alternatives. These are your negotiating variables: what you must have, what you are willing to give up, what alternative solutions there are, and what point you’re willing to walk away. It is to your advantage to be prepared with the answers to these questions so that you grasp all the potential outcomes of the negotiation.

Houfek recommended to us that the best platforms for negotiating, from most effective to least effective are in person, via face to face digital, over the telephone, and through email.

You’re curious about what Science meeting I was at? I get it. It was C-DEBI.

background: Did you know that up to 1/3 life (biological matter) may exist in fluids that circulate through Earth’s crust, deep down, below the sediment, at the very bottom of the ocean? Scientists estimate every 70,000 years, 2% of the ocean’s volume gets circulated (that is roughly the same volume of water is all of Earth’s rivers). There are many unknowns with respect to the types of micro-organisms that exist in the circulating fluid, how long they live, what conditions they are able to survive in, the types of reactions that they utilize to gain energy, and their influences on the fluid geochemistry.

To fill in the knowledge gaps about the life is circulating through Earth’s crust, the National Science Foundation funded the Center for Dark Biosphere Investigations (C-DEBI), a multi-year, multiphase, interdisciplinary research project. C-DEBI hosts an annual meeting two-day meeting where contributing scientists convene to present their work and connect about future projects. In addition to the science meeting, there is a development workshop targeted for graduate students (what you read about in the main post). Some of the research funded by C-DEBI was the focus of the Ship to Shore outreach cruise I participated on and posted about here.

Hello, welcome to Oceanbites! My name is Annie, I’m a marine research scientist who has been lucky to have had many roles in my neophyte career, including graduate student, laboratory technician, research associate, and adjunct faculty. Research topics I’ve been involved with are paleoceanographic nutrient cycling, lake and marine geochemistry, biological oceanography, and exploration. My favorite job as a scientist is working in the laboratory and the field because I love interacting with my research! Some of my favorite field memories are diving 3000-m in ALVIN in 2014, getting to drive Jason while he was on the seafloor in 2017, and learning how to generate high resolution bathymetric maps during a hydrographic field course in 2019!