This week is #BlackInMarineScience week and here at Oceanbites we’re featuring the work of Black scientists all week long! Today’s post is featuring work done by Dr. Ayana Johnson on coral reefs and how best to manage them under changing ocean conditions. Read on to learn a bit about Dr. Johnson and her research.

Meet Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson

Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson is a distinguished marine biologist. She received a B.A. from Harvard University in Environmental science and Public Policy, a M.Sc. from Scripps Institution of Oceanography and a Ph.D. from Scripps Institution of Oceanography in marine biology. Her dissertation research focused on the ecology, socio-economics and policy of sustainably managing coral reefs. Prior to attending graduate school, she was an Environmental Scientist at the US Environmental Protection Agency. She has received multiple fellowships for her research efforts.

Mostly notably, she won a National Geographic Solution Search Award for a fish trap she invented during her Ph.D. that reduces bycatch. Now she works at the intersection of research, science communication and policy. Dr. Johnson founded the Urban Ocean Lab which is a think tank for the future of coastal cities. As a Brooklyn native, she is passionate about urban ocean conservation and approaches climate problems with a multi-disciplinary lens. Check out her website for a more detailed bio and to read more about her impressive accomplishments.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This post is in support of #BlackInMarineScience week highlighting Black scientists who have contributed to and are currently working in the marine science field. To find out more visit https://blackinmarsci.github.io/index.html.

Citation: Johnson, A.E., Jackson, J.B.C., 2015. Fisher and diver perceptions of coral reef degradation and implications for sustainable management. Global Ecology and Conservation 3, 890–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2015.04.004

What lies below the waves (…or doesn’t)

Coral reefs are beautiful little cities that are important for numerous reasons. They protect coastlines from storms and erosion and provide both jobs for local comminutes (ie., fishing) and recreational opportunities (ie., snorkeling/SCUBA diving). Unfortunately, Caribbean island reefs have been damaged due to overfishing, constant coastal development, pollution and climate change.

It is possible to protect coral reefs through management practices; however, this can be incredibly difficult due to public perceptions known as a shifting baselines. A shifting baseline means that people using the coral reef systems (ie., divers) don’t have a full appreciation for where coral reef health started when compared to reef health today. In other words, their baseline of a healthy reef is more optimistic. This idea is explored in a study by Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson who set off to understand how to best manage coral reefs.

How to figure out the best management practices?

Dr. Johnson carried out a case study on the islands of Curaçao and Bonaire. Between the two islands, she interviewed 177 full time and part-time fishers and 211 professional SCUBA divers. All the fishers were grouped together and represented small-scale fishing operations because industrial fishing does not exist on either island. The interviews were conversational and casual in nature as Dr. Johnson felt this was the best way to get local participation. Interviewees ranged in age and expertise and were asked about their opinions related to perceived causes of changes in fish abundance and reef conditions, and support for management efforts.

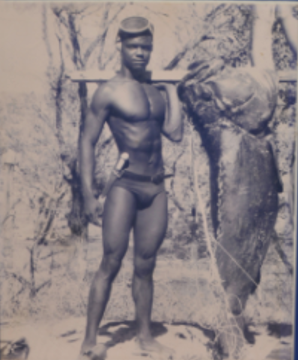

Dr. Johnson found that fishers’ and divers’ anecdotes mimic the scientific evidence, citing that the “coast is now a desert” compared to what they experienced or the stories they were told. Although divers had a brighter view of health of coral reefs and fish populations, both fishers and divers agreed that the fish have gotten smaller (you can get an appreciation for how large the fish used to be in the image to the right). In fact, Dr. Johnson interviewed one diver that said, ‘‘I miss the big fish. Some places it’s like diving in a saltwater aquarium—all these little fish.’’

This more optimistic view is likely from the idea of ‘shifting baselines’, where divers are generally younger, have a higher turnover rate and have less of a family history in diving so they don’t have an appreciation for the timeline of reef degradation. In addition, race played a role in differing opinions – most fishers were black and Antillean whereas most divers were white and foreign. Even though there were many differences in the responses between fishers and divers, both groups agreed that: 1) the health of the reefs and fisheries is threatened and 2) better management is needed to turn the situation around.

Moving forward to sustainably manage coral reefs

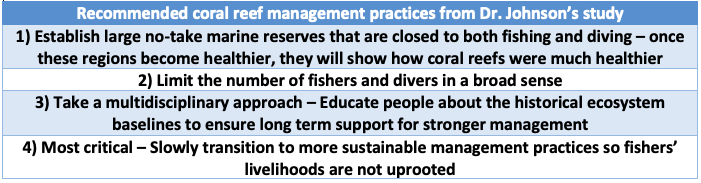

It seemed that fishers blamed divers for reef destruction and vice versa. However, both groups can cause significant damage to the coral reef ecosystem. Generally, fishers get more blame for environmental destruction because the effects from fishing are more immediate. On the other hand, divers and tourism can be just as bad when people kick and touch reefs and use harmful sunscreens. Regardless of the types of destruction, it is clear that something has to change because livelihoods rely on a solution. The only way to conserve peoples’ livelihoods is to make a slow transition to more sustainable management practices. In addition, Dr. Johnson outlines the following guidelines for sustainably manage coral reefs, highlighting a slow transition is crucial:

I love writing of all kinds. As a PhD student at the Graduate School of Oceanography (URI), I use using genetic techniques to study phytoplankton diversity. I am interested in understanding how environmental stressors associated with climate change affect phytoplankton community dynamics and thus, overall ecosystem function. Prior to graduate school, I spent two years as a plankton analyst in the Marine Invasions Lab at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) studying phytoplankton in ballast water of cargo ships and gaining experience with phytoplankton taxonomy and culturing techniques. In my free time I enjoy making my own pottery and hiking in the White Mountains (NH).