Smale, D. A., Wernberg, T., Oliver, E. C., Thomsen, M., Harvey, B. P., Straub, S. C., et al. (2019). Marine heatwaves threaten global biodiversity and the provision of ecosystem services. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 306–312. DOI: 10.1038/s41558-019-0412-1

Heatwaves in Australia are stoking the flames of the wildfires currently ravaging the country. While the effects are not as visible, the ocean, too, is suffering from extreme temperatures. Recent research reveals that underwater heatwaves are escalating, with devastating impacts.

Since the dawn of the industrial age, humans have burned vast amounts of fossil fuels and cut down huge swaths of forest, pumping heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere. But only about one percent of the trapped heat actually stays in the air; the ocean absorbs most of the remainder. Because the ocean is so vast, and because it takes so much energy to heat water—a watched pot never boils, after all—the ocean has been slow to warm. But warm it slowly and surely has, and at an ever-accelerating pace.

Superimposed on this gradual warming of the entire ocean is the sharp increase in the number of marine heatwaves—spikes in temperature that persist for five or more days. These extreme temperatures affect the underwater environment, with socioeconomic and political implications. For instance, in 2012 a heatwave in the Northwest Atlantic caused lobsters to mature early, resulting in a record number of catches which sent prices plummeting and ensued in a lobster war between American and Canadian fishermen. As marine heatwaves escalate, so too will the disruption on the goods and services provided by the ocean.

Spiking a Fever

Marine heatwaves can be caused by a number of processes. On a local scale, air-sea heat flux can warm the ocean surface from the atmosphere. On a large scale, ENSO (no, not a Star Wars character, but rather a natural climate phenomenon) influences temperature and rainfall patterns across the globe. While the drivers are complex, one thing is certain: marine heatwaves are becoming more frequent and prolonged.

A rise in extreme temperatures in the ocean does not only spell trouble for its inhabitants, but also for us humans. We rely on the sea for food, oxygen, storm protection, and carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere. While wildfires on land may have captured most of our attention, the heatwaves sweeping the underwater world are no less alarming.

In a recent study published in Nature Climate Change, a team of scientists led by Dan Smale and Thomas Wernberg sought to systematically analyze trends in the occurrence of marine heatwaves, and examine their impacts on natural areas and wildlife.

Tracking Underwater Wildfires

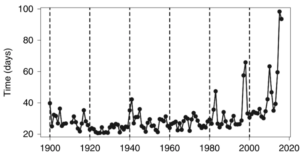

The team started by tallying up the annual number of marine heatwave days since the beginning of the twentieth century, using a combination of sea surface temperature datasets and models, to track how much they are on the rise. Next, they looked at global patterns to pinpoint regions where increasing heatwaves overlap with vulnerable areas—waters that are rich in sea life, that are home to temperature-sensitive species, or that are already experiencing other human stressors such as overfishing and pollution.

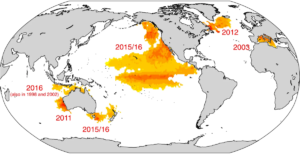

The scientists then turned their attention to assessing the impacts of marine heatwaves on ocean life and human society. To do so, they conducted an exhaustive literature review, combining data from well over one hundred research papers that documented eight major marine heatwaves (such as the 2011 “Ningaloo Niño” off Western Australia, and the 2013 “Blob” in the northeast Pacific) and their impacts on everything from tiny plankton to fish to seabirds. They then examined how these impacts will affect the ocean’s ability to provide for humanity.

Some None Like it Hot

After much number-crunching, the verdict isn’t great. In the thirty-year period prior to 2016, the number of marine heatwave days occurring per year has increased by over 50% compared to the same period prior to 1954. In the last few years alone, heatwaves have tripled in frequency. Maps examining global patterns in marine heatwaves reveal that multiple regions across the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans are particularly at risk.

While the eight well-studied marine heatwaves varied greatly in terms of extent, duration, and intensity, all had negative impacts on marine life. Species that are incapable of moving are affected the most by marine heatwaves. Critically, heatwaves are killing off coral reefs, kelp beds, and seagrass meadows. These aptly termed “foundation species” are the underwater equivalent of forests, providing shelter and food to other ocean life.

Even mobile species are not immune; while they can try to flee to colder waters, they may not be able to escape fast enough. Already, severe marine heatwaves have caused plants and animals to retreat over 100 km northward from the equator. And marine life is cropping up in unexpected places, such as in 2018, when rare tropical fish from Australia appeared in New Zealand, having swum 3,000 km across the Tasman Sea to escape a heatwave.

All of these changes have ripple effects on human society. Whether directly or indirectly, we all depend on the ocean for various services ranging from food to storm protection to recreational activities. Abnormal warming events wreak havoc to commercial fisheries. They alter underwater habitats, reducing natural coastal defenses. They cause non-native species to invade waters where they don’t belong, and fuel blooms of toxic algae. As marine heatwaves intensify, we can expect economic losses in fisheries, aquaculture, and tourism to increase in lockstep.

In Hot Water

While names like the “Blob” don’t exactly inspire terror, marine heatwaves are no laughing matter. Scientists have mainly focused on trends in average global sea surface temperature, but this study reveals that localized, short-lived warming events are also pivotal in altering ocean systems. As human-induced climate change continues, record-breaking temperatures are becoming the new normal. Unless we take decisive steps—such as achieving the 2 degrees Celsius target set in the Paris Agreement—we have only ourselves to blame for the loss of ocean services that we depend on. ■

I am a Ph.D. candidate at Boston University where I am developing an underwater instrument to study the coastal ocean. I have a multi-disciplinary background in physics and oceanography (and some engineering), and my academic interests lie in using novel sensors and deployment platforms to study the ocean. Outside of my scholarly life, I enjoy keeping active through boxing and running and cycling around Boston.