In the spirit of the games:

There is a certain spirit in the air during the Olympics – the embrace of friendly competition, a showcase of national and athletic diversity, and a joyful celebration of human achievement. With the Olympic season upon us, let us examine evolution at its grandest by diving into some of Earth’s records held by marine life:

Largest creature – Blue whale. Not only the largest living species today, the blue whale is also the largest species to have ever lived, reaching a whopping 30 m, three times the distance of tallest platform dives! For some more visuals of their size, check out this video. You can only imagine how much food it takes to fuel a blue whale!

Deepest living fish – Snailfish. Resembling a pink tadpole, but measuring over 9 cm, these fish are found in the Mariana Trench at a depth of over 8000 km, which is roughly equivalent to the travel distance between Tokyo, Japan and the 2024 Olympic site in Los Angeles, California. At this depth, they experience huge amounts of pressure! To put it into perspective, imagine the pressure you would feel from three times the Olympic weightlifting clean and snatch world record on top of you! To see them in their natural environment, check out this video.

Oldest animal – Sponge. Their motto: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”. Sponges have been around for at least 540 million years, and little changed from their debut. They have managed to outlive many global extinction events, which may be attributable to their simple body structure and colonial lifestyles. With this track record, you can expect them to hold onto their title for years to come.

Deepest diving animal – Cuvier beaked whale. These deep-sea specialists reach record breaking depths of 2992m, or close to 60 lengths of an Olympic swimming pool, in just one breath! Their dives often last over 2 hours as they hunt for squids and other prey. For a virtual dive, click here.

Most powerful bite — Saltwater Crocodile. This may be no surprise to those of us who marvel over animal documentaries, witnessing the vice grip of these reptiles. These ferocious beasts have a bite measuring 3,700 pounds per square inch (psi), at least 10 times as powerful as a Rottweiler’s jaw!

Most abundant – Bacteria. Although not visible to the naked eye, bacteria are numerous in each drop of water, up to one million individuals in one mL (1/5 of a teaspoon) of seawater. Bacteria play a variety of important roles in our oceans, ranging from recycling essential nutrients to producing 25% of the Earth’s oxygen (thanks, bacteria!).

Fastest animal – Sailfish. Fast and furious, the sailfish travels up to 108 kilometers per hour when chasing schools of fish, squid, or octopus. To put this in perspective, this speed is close to 3 times as fast as Usain Bolt’s 100m world record! Much like the cheetah, the sailfish’s strategy is to injure and outrun its prey before going for the kill.

Most venomous – Australian box jellyfish. Although seemingly innocent, this 30-centimeter-wide jellyfish can sting-to-kill in under 5 minutes! They also possess the ability to swim (unlike other jellyfish that merely drift) and detect light and vibrations, suggesting that they are capable of actively hunting! Sounds quite ominous.

Longest migration – Gray whale. Recent record-holders, a pod of gray whales was found to have journeyed 26,876 km on their annual migration — from the northwest part of the Pacific Ocean, up through the Arctic Ocean, down the Atlantic Ocean, and ending along Africa’s western coast. This record was previously held by Leatherback turtles who traversed an impressive 20,510 km across the Pacific Ocean.

Fastest punch – Peacock mantis shrimp. Seemingly welcoming with their enticing colors, the mantis shrimp strikes with its club-like appendages when threatened. They snap together at a speed of 23 m/sec, roughly double the speed of a professional boxer. This punch is so fast, in fact, that a bubble is formed due to the surrounding water vaporizing! To see this punch in action, check out this video.

The main event:

Earth’s magnificent record holders are a true spectacle! While our Olympic athletes are crafted over a lifetime of training, blood, sweat, and tears, these marine champions have been forged over millennia! Natural selection has favored survival of the fittest in the ongoing competition of life. This dynamic process has led to a variety of unique strategies, extreme power and size, and wondrous diversity across the tree of life.

The breadth of this marvelous diversity provides us with many services including ecosystem resilience, food and other economic resources, groundbreaking medical discoveries, and immense cultural value. However, it is no secret that we are en route to the 6th largest mass extinction due to the intensity and speed at which humans are altering the environment and threatening much of this rich diversity.

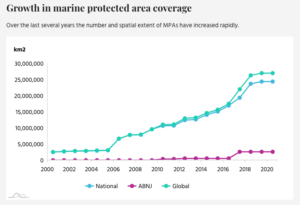

To minimally safeguard this diversity, the International Union of the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) recommends protecting 10% of global oceans by 2020 and working towards 30% by 2030. With 2020 now behind us, how did we fare in reaching this goal? Currently, 5-7% of the global oceans are under some kind of protection. The majority of these protected areas are situated within national waters, which in sum represent 39% of our ocean surface and 5% of its volume, meaning we still have a lot of ground to cover. Although rates of conservation have increased in the last 20 years, it is expected that we will not reach recommended levels of protection until 2100, which may be far too late for many species!

Is it possible to expedite this? How about encouraging national excellence in the same vein as the Olympics? Although it only happens every 4 years, we cannot forget that the Olympics, as a planned event, is a year-round business with dedicated representatives globally and full-time athletes. Heck, the Olympics are even planned out, to some degree, years in advance with host countries placing bids 10 years before the event! Nonetheless, the efforts of each participating nation, athlete, and sponsoring company allow the program to be the showstopping event we look forward to time and time again. Such an ongoing, organized global effort suggests that the same showmanship made towards the Olympics can be made towards protecting our oceans to not only ensure that the spectacles continue to amaze us, but also continue to sustain us. Imagine a world in which each nation is eager to brag about the size of their marine protected areas and astonishing rates of recovery observed in their waters! And the first medal of the the World Championship of Marine Conservation goes to…

I am a PhD candidate in Biological Oceanography at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. I use DNA found in the environment (eDNA), like a forensic scientist, to detect deep-sea animals and where they live. When I am not studying the ocean, I am most likely in the ocean surfing or diving along the beautiful coasts of O‘ahu.