This post is part of a semester-long collaboration with Dr. Michèle LaVigne, a professor at Bowdoin College, who partnered with oceanbites authors to incorporate science communication into her Oceanography classes. This is a guest post co-authored by two of her Oceanography students, Alexis Mullen and Bridget Patterson. Their brief biographies are below and their post follows:

Alexis: “Hi! My name is Alexis and I’m a sophomore at Bowdoin College studying Earth and Oceanographic Science, Anthropology, and Dance. I’m interested in coastal oceanography and sustaining fishing communities. I enjoy sunshine, listening to and playing good music, and spending time with my friends outside. This summer I’ll be working as a Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) intern at Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, researching the link between physiological thermal thresholds to the distribution of juvenile lobsters.”

Bridget: “My name is Bridget and I’m class of 2023 at Bowdoin College. I’m majoring in Biology with a concentration in Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology with a minor in Earth and Oceanographic Sciences. I’m specifically interested in coastal ecology. Outside of class, I spend a lot of time in student-run theatre and the Bowdoin Queer-Straight Alliance. This summer I’m a Doherty Coastal Studies Center Fellow, working on discovering whether or not Idotea balthica, a small grazer in seagrass ecosystems, locally adapts to temperature differences in the Gulf of Maine.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Original journal article:

Nathan J. Bennett, Elena M. Finkbeiner, Natalie C. Ban, Dyhia Belhabib, Stacy D. Jupiter, John N. Kittinger, Sangeeta Mangubhai, Joeri Scholtens, David Gill & Patrick Christie (2020) The COVID-19 Pandemic, Small-Scale Fisheries and Coastal Fishing Communities, Coastal Management, 48:4, 336-347, DOI: 10.1080/08920753.2020.1766937

Since early 2020, the novel coronavirus has spread across the world, infecting and killing millions of people. Globally, small fishing communities are being hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important that we understand the effects of COVID-19 on fishing communities because the issues created by the pandemic can help inform future policy and societal support for these vulnerable communities.

Stonington, Maine and its lobstering community can serve as an example for some of the struggles experienced by small fishing communities worldwide. I (Alexis) had the privilege to spend last summer working in the small lobstering community of Stonington, Maine. Located on Deer Isle, Stonington is the self-proclaimed “Lobster Capital of Maine” and before the COVID-19 pandemic hit in Spring of 2020, Stonington’s annual lobster landings were valued at $50.89 million. This number has dropped significantly since 2016, when Stonington’s lobster landings peaked at $68.03 million per year. The decline of landings can be attributed to late lobster molt, the cost and availability of bait, as well as rapidly warming waters in the Gulf of Maine. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic added to the already stressed lobstering communities and exacerbated the industry’s decline. Health concerns from the novel COVID-19 coronavirus became apparent in China just before the Chinese New Year in 2020, ceasing celebrations and causing a decreased demand for luxury seafood such as Maine lobster.

Recently, a study has collected reports from both scientific and news sources about the effects that COVID-19 is having on small fisheries. The report suggests that there have been both positive and negative effects, both for the communities of fishers and the animals they are fishing.

Lobsters, or Homarus americanus, like this one, are captured by fishermen in “landings.” The amount of lobster caught in each landing can be affected both by changes made by fishermen and changes or shifts in the lobster community. Such changes include changes in timing of maturity among lobsters, or changes in bait made by fishermen.

COVID wreaks havoc on lobstering communities

COVID-19 has caused changes for everyone, lobstering communities included. Globally, social distancing requirements completely shut down many small, local fisheries because fishermen cannot distance on boats. These requirements prevented many fishermen from making any sort of income to support themselves and their families. In addition, there are many communities that rely on fish as a source of food so without local fisheries, these communities have lost an important piece of their diet. Even if a fishery was able to stay open, a breakdown in the supply chain such as a limited supply of cold freezers or shipping issues, stopped many fishers from being able to sell their product. Finally, a decrease in demand for seafood that stemmed mainly from restaurant shutdowns drastically decreased the prices of any fish that happened to be sold.

Not only have these communities suffered economically, but they are also vulnerable to COVID-19. Globally, many fishing communities are populated by migrant workers whose movement makes both them and their communities vulnerable to COVID-19. In India, for example, migrant workers have been stranded on their vessels or in harbors, quarantining, unable to return home or enter port. In addition, international visitors and tourists increase these communities’ exposure to COVID-19. With people coming in from around the world to see and experience these fisheries, germs are brought in from a number of places and can potentially expose people to COVID-19.

Marine populations are also especially vulnerable as a result of the pandemic. Ecologically, COVID-19 has meant a break in monitoring marine protected areas, possibly increasing the occurrence of illegal fishing. These instances could severely harm the biological communities that are being fished.

A small silver lining from COVID

While COVID-19 has been detrimental to public health, there have been some positive impacts to small fishing communities. For example, there has been increased community building through the ‘local food’ movement and collective action, such as petitions. Staying close to home also means people have been buying more local food. This local support has increased the amount of fish consumed by fishing communities and has managed, in some cases, to support fishermen through this difficult time. For example, in Oaxaca, Mexico, local fishers are contributing their time and boats to collect fish to feed their communities. These fishers have managed to bring in 10,000 to 12,000 pounds of fish each week. In addition to local food consumption, collective action has helped build community among fishermen. Another example of collective support is seen through the South African small-scale fisheries collective that convinced the Department of Fisheries to reopen small scale fisheries amidst the pandemic. Measures like these, taken by small collectives, help create and maintain a sense of community among fishermen.

There have also been positive impacts for the fish as the reduction in fishing has enabled stocks to increase during the pandemic. The combination of social distancing, lockdowns, and decreased demand or price has meant fewer fish are collected. For instance, boats are out of port (or in other words, fishing) for eighty percent less time than during the same period in previous years. The result of these changes is that fish have been more able to live and reproduce without interference, which has allowed their populations to increase.

Turning over a new leaf: some solutions to the problems caused by COVID

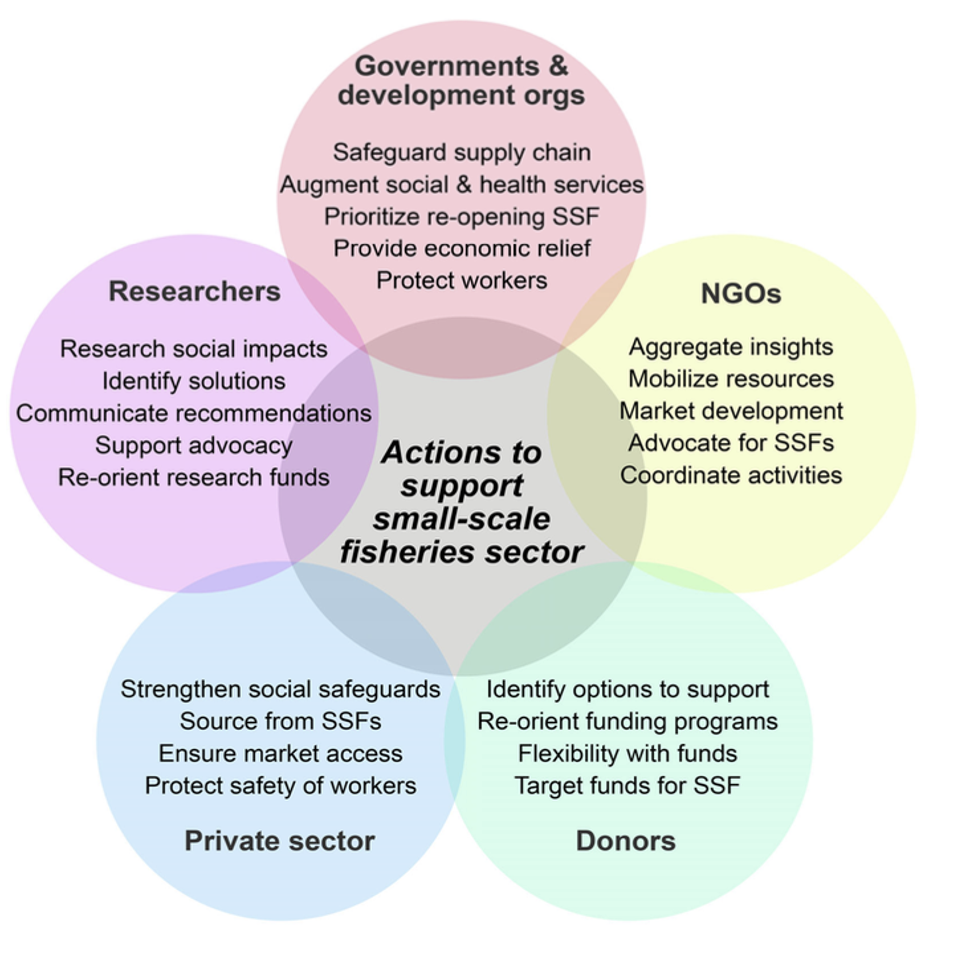

On a large scale, COVID-19 has revealed societal problems and inequalities previously overlooked. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs), governments, and researchers all have parts to play in helping create the recognition of the importance of these communities. NGOs can help by mobilizing resources for these communities and supporting their attempts at community action. Governments must focus on reopening their countries while providing economic relief and protecting the supply chain that fisheries rely upon. Finally, researchers play an important role through investigating specific social impacts of COVID-19 and communicating recommendations for mediating these impacts.

According to the paper, there are several groups who can help support small fisheries. Each group has something unique to contribute, each essential to the well-being of small fishing communities. However even on the small scale, there are actions we all can take to help support fisheries and the people who work and live in fishing communities. Many fishing communities depend on revenue both from fish and tourism. Last summer in Stonington, the number of tourists significantly decreased. Despite the risks associated with traveling during the pandemic, Maine’s culturally-rich fishing communities are also at risk if fishermen, restaurants, and other businesses are not supported. There are a few different ways we would suggest supporting small fishing communities. Firstly, if you are going to visit, make sure to wear your mask! Secondly, we recommend ordering take-out from restaurants, if possible, to minimize the exposure to locals. We also recommend determining how to buy fresh, delicious fish from local fishermen.

For instance, you can ask around in town or snoop around on the town’s Facebook page. If you are unable to make the trek to your favorite small fishing town in the near future, try looking up local nonprofits that support the overall survival of small fisheries. One of these examples is the Maine Center for Coastal Fisheries, where Alexis interned last summer.

Finally, it’s important to acknowledge the fact that indigenous communities in Maine are especially vulnerable during the pandemic and although they are the rightful owners of the land we inhabit here, their fishing and river rights have been taken away in many instances. To protect and advocate for these communities, do your part to minimize the spread of COVID-19. It is necessary to learn about and acknowledge indigenous history on the lands you visit and donate to organizations that fight for native peoples’ rights. For more information, please see the following resource: https://www.firstnations.org/covid-19-emergency-response-fund/

I love writing of all kinds. As a PhD student at the Graduate School of Oceanography (URI), I use using genetic techniques to study phytoplankton diversity. I am interested in understanding how environmental stressors associated with climate change affect phytoplankton community dynamics and thus, overall ecosystem function. Prior to graduate school, I spent two years as a plankton analyst in the Marine Invasions Lab at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) studying phytoplankton in ballast water of cargo ships and gaining experience with phytoplankton taxonomy and culturing techniques. In my free time I enjoy making my own pottery and hiking in the White Mountains (NH).