Marine heat waves, climate change, and failed spawning by coastal invertebrates. 2020. Shanks, A.L., Rasmuson, L.K., Valley, J.R., Jarvis, M.A., Salant, C., Sutherland, D.A., Lamont, E.I., Hainey, M.A.H., and R.B. Emlet. Limnol. Oceanogr. 65: 627-636

Marine Heat Waves

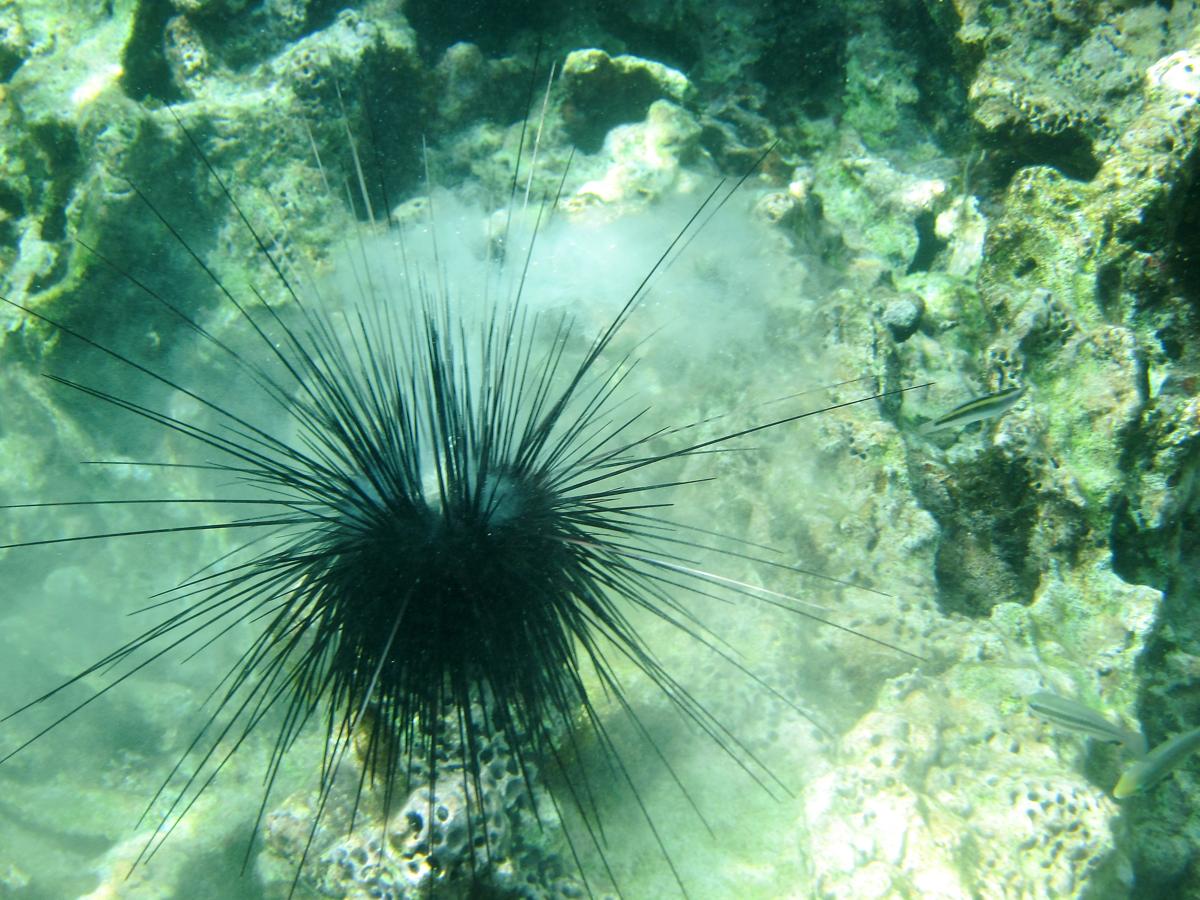

Human caused climate change is increasing temperatures not only on land, but in the oceans as well. Heat waves are becoming more frequent, longer, and more extreme. Scientific models also suggest that the frequency of these Marine Heat Waves (MHWs) will only continue to increase. These heat waves can have dramatic effects on marine animals, for example bleaching marine corals and disrupting food webs. We still don’t know whether (or how) these MHWs affect the early life stages of marine invertebrates like bivalves, crustaceans, and sea urchins, crucial members of marine ecosystems.

Marine Heat Waves

Most marine invertebrates reproduce by broadcast spawning, a process where animals release eggs and sperm into the water. These eggs and sperm, or gametes, must come into contact with each other for spawning to be successful and lead to embryo development. Most invertebrates live near coasts, but juveniles migrate out towards the open ocean to develop away from coastal predators and turbulence. Researchers from the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology recently investigated spawning success across years with a high frequency of MHWs, which dramatically affected the success of invertebrate spawning.

The Experiment

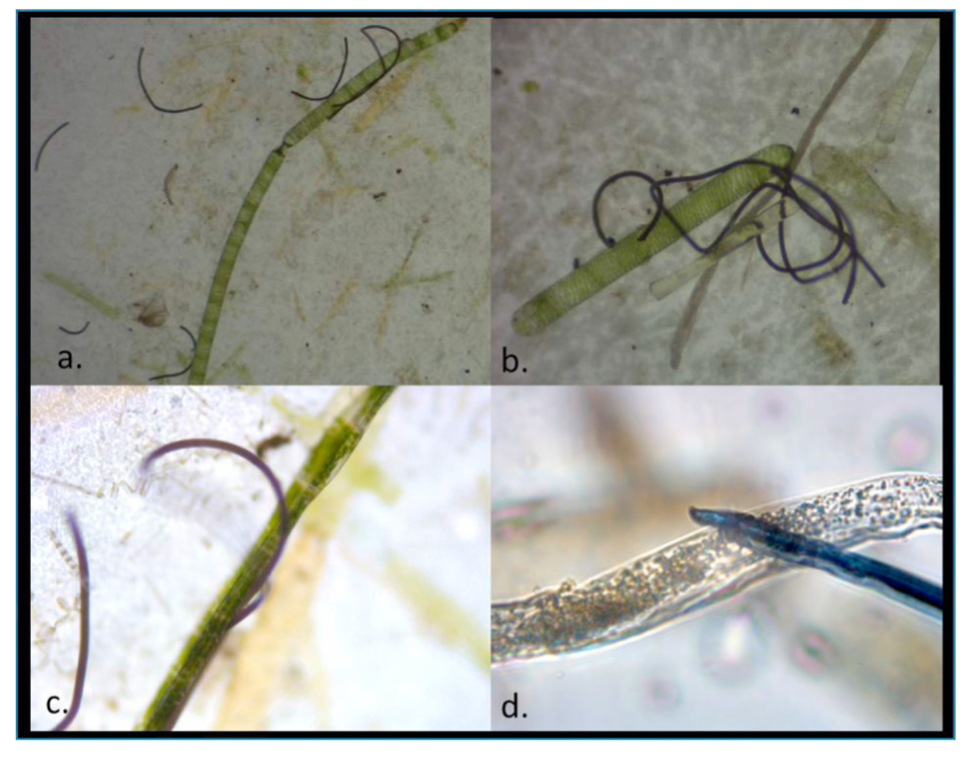

In order to look at spawning success the researchers collected daily water samples at high tide from the end of a dock at their institute from January to March of 2014, 2015, and 2016. This dock was near the end of an estuary and received water from the coastal ocean consistently. Water was pumped through several filters to get rid of both big and small debris, and to get embryos in the middle size range (between 125 micrometers and 1 centimeter). The number of embryos and juvenile animals were used to determine spawning success. Larvae and embryos from these water samples were counted, photographed, and identified as closely as possible, before being frozen for later genetic analysis. They also took temperature and salinity measurements of the water. The researchers then compared the daily average and annual abundance of embryos across the three years and looked at how the temperature and salinity of the water also changed from 2014-2016.

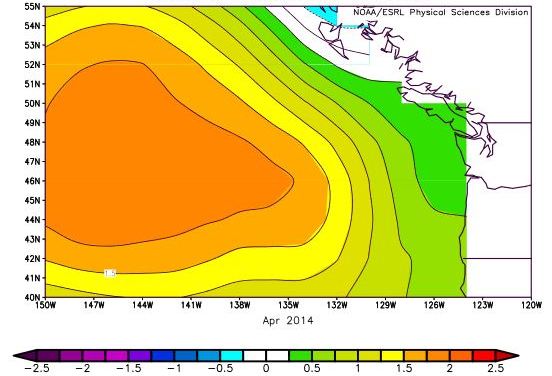

During the winter 2015 sampling, the researchers saw an anomalously warm “blob” of water, very characteristic of a MHW, move to the Oregon shore. Temperatures in 2015 and 2016 were much higher than in 2014, and salinities were significantly lower in those years as well, all indications of a marine heat wave. When they compared the average number of embryos across years, they found that spawning success in 2015 and 2016 (the warm years) was much lower than in 2014.

Climate change, marine heat waves, and spawning success

So why does warmer, less salty water decrease spawning success? It’s possible that high temperatures cause adult animals to die off, and no adult population means there’s no one left to spawn. Warmer temperatures could also have slowed down the development of gametes or stopped the production of sperm and eggs altogether. Or the ocean conditions that trigger spawning in many species may not have happened during these marine heat waves.

Whatever causes these spawning failures, it’s definitely related to the warming of ocean waters and human caused climate change. Even a small decrease in spawning success could have far reaching effects on invertebrate populations, and the science is clear: marine heat waves are becoming more common, larger, and hotter because of climate change.

It’s sometimes hard to feel hopeful about the future when the science is so dire. However, there’s good news on the horizon. The United States has rejoined the Paris Climate Accord, signaling a recommitment to climate policy. The new Presidential administration has also made a pledge to make the United States carbon neutral by 2050. Individual people can also take steps to reduce their own carbon footprint and help the country reach this goal.

Try:

-eating less red meat, or buying local

-buying energy efficient appliances

-taking public transportation instead of driving

-keep the climate conversations going with family and friends

-advocate and vote for green policies

I’m a PhD student in Oceanography at the University of Connecticut, Avery Point. My current research interests involve microplastics and their effects on marine suspension feeding bivalves, and biological solutions to the issue of microplastics. Prior to grad school I received my B.S in Biology from Gettysburg College, and worked for the U.S Geological Survey before spending two years at a remote salmon hatchery in Alaska. Most of my free time is spent at the gym, fostering cats for a local rescue, and trying to find the best cold brew in southeastern CT.