Summertime, shearwaters, and satellites

How do we know where seabirds like to hang out? Up until the past few decades, this question was a tall order. Seabirds like the Great Shearwater, Ardenna gravis, are notoriously mobile; they migrate across huge stretches of the sea to find food and raise chicks at specific locations.

Tracking these marathon treks has proven difficult until the advent of recent telemetry technology. Telemetry entails the remote measurement of information like location that is then transmitted to the user through satellite communications. The satellite-enabled tags that allow this sort of data collection are now tiny enough to fit on the back of a 700 gram, or ~1.5 pound seabird, opening up a whole new world for seabird scientists over the past 10-15 years.

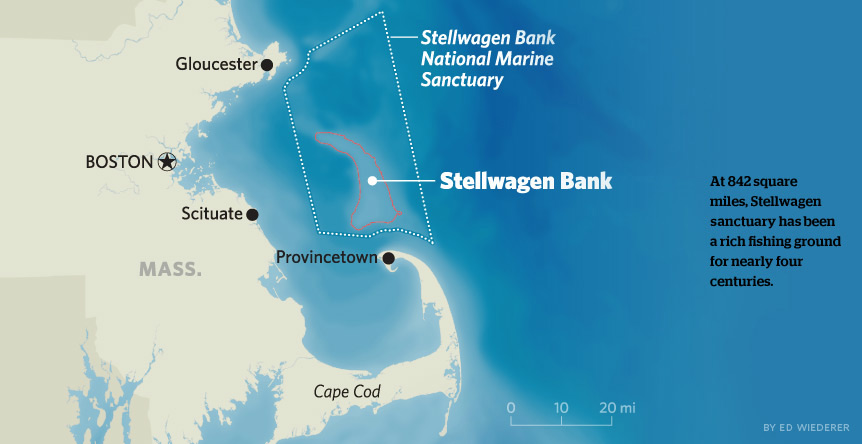

NOAA’s Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary (SBNMS) supports just such a team of researchers. The team consists of seabird biologists from USFWS, along with researchers from Boston University, Long Island University, SBNMS, and University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography. Each team member brings a valuable skill set to the table, seeking answers to different but complimentary questions about bird diet, habitat use, and food web pollutants (I’m the pollutant researcher!). Since 2013, the SBNMS Shearwater team has convened in July or August to attach satellite tags, called platform transmitter terminals or PTTs , to the backs of Great Shearwaters caught in and around SBNMS in Massachusetts Bay.

Great Shearwaters are seabirds that live almost exclusively at sea, only coming to land to raise chicks on remote islands in the middle of the South Atlantic. During the summer months, the birds migrate across the Atlantic Ocean and fatten up in the rich waters of the Gulf of Maine, feeding on forage fish and squid. The shearwaters act as great food web and environmental indicators, because they travel to find optimal food and ocean conditions, thereby indicating what regions have the best food resources and are capable of supporting commercially important fish and megafauna like whales and sharks. The Gulf of Maine is warming extremely fast due to climate change, so it’s important to understand where marine life is finding food and optimal habitat under these changing conditions.

Step 1: Catch a seabird…harder than it looks

The team set out on July 9, 2018 from Chatham, MA to catch seabirds aboard the R/V Auk; the Auk is a 65’ vessel that is capable of launching a small inflatable boat while at sea, letting researchers get closer to the birds via a small boat while providing the safety of a large vessel as home base. Prior to departure, the team chatted with local fishermen and other scientists to figure out where whales and birds had recently been spotted in the region. About two hours into the trip, we hit jackpot: we found whales and birds feeding, with large rafts of Great Shearwaters ripe for sampling.

To get the seabirds on board, we started baiting the water with pieces of fish and squid. Though unglamorous and quite smelly, the bait acts to draw the birds closer to the small boat, within the reach of a long-handled net. Catching birds can take hours of baiting or just a few minutes, depending on how hungry the birds are. On this particular trip, we were lucky-the birds were hungry and approached the boats readily with the promise of food.

Once netted, the birds are quickly put into an animal carrier with special netting, to allow the birds to sit quietly out of the sun while the small boat returns to the Auk.

Once aboard the Auk, the real fun begins (for the researchers, not so much for the birds). Under permit and using vet-approved techniques, the team collects a wealth of samples from each bird to figure out what the bird has been eating, how old it is, when it last shed its feathers, what contaminants are in its body, and how it compares in size to other caught birds. This entails taking blood from the bird’s leg, catching its exhaled gases while it is breathing, measuring the length of its wings, beak, and legs, and taking a few feathers, all while avoiding its sharp and nimble beak. The samples are taken as quickly and safely as possible, to minimize the amount of stress on the bird while being handled. After all these samples are taken, the satellite tag is attached to the bird’s back via a tried-and-true method using sutures , or stitches, just below the bird’s skin.

Seabirds: environmental indicators in a changing region

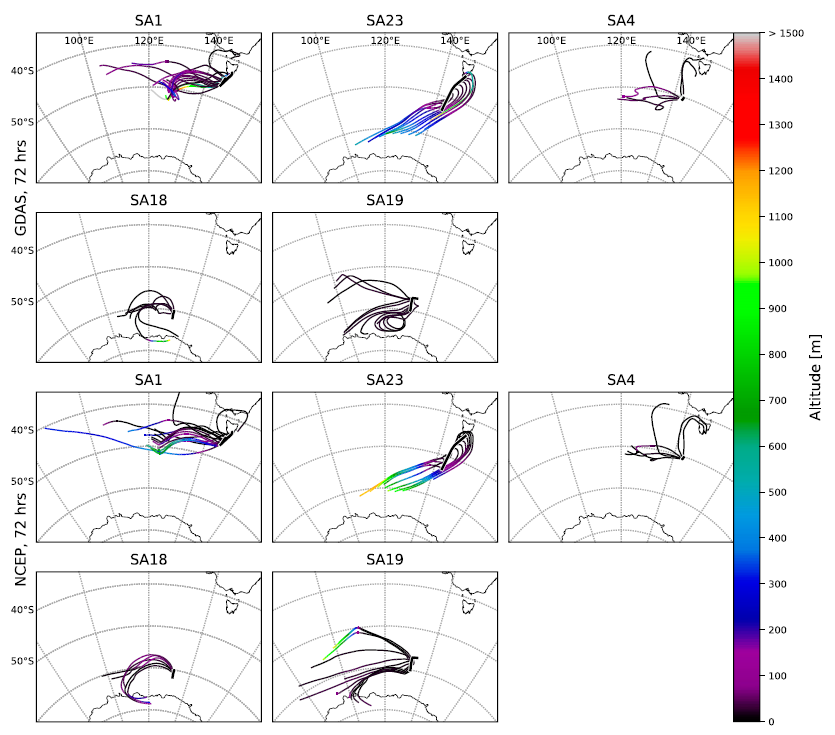

The tag is programmed to send the bird’s location to a satellite every three hours around the clock, allowing the team to understand how the birds are using their Gulf of Maine feeding grounds over the course of the summer. Tags remain attached up to 200 days, sending information back to researchers over the whole deployment before falling off while the bird continues to move and migrate.

Some results of this tagging effort have already been published and summarized here, but the tagging work is planned for at least another three years because of how valuable the collected data is. Seabirds like the Great Shearwater are excellent environmental indicators; they move around to follow food and optimal oceanographic conditions, so by following their movements, we know which areas in the region are most productive and supporting other creatures like commercially important fish or whales. The Gulf of Maine is warming faster that 99% of the ocean, so understanding where marine life is finding food under these changing conditions is vital so we can best work to protect these areas and mitigate the effects of climate change in the region. Understanding where the birds like to hang out also means we can work to reduce bycatch, or the accidental landing of seabirds in gill nets and longline fisheries.

To keep tabs on the birds over the tagging season, follow @track_seabirds on Twitter, or reach out to team members @tammylsilva or @annaruthski on Twitter with more questions!

I am a third year PhD student at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography in the Lohmann Lab. My current research interests include environmental chemistry, water quality, as well as coastal and seabird ecology. When not in the lab, I enjoy diving, surfing, and hanging out with my dog Gypsy.