Paper: Back from the dead? Not really. The tale of the Galapagos shark (Carcharhinus galapagensis) in a remote Brazilian archipelago DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109097

Tails of Extinction

In recent decades, there has been a significant effort to conserve threatened or endangered species. Countless campaigns to protect wildlife, from polar bears to orangutans, have pushed to preserve habitats and stop poaching. Some of these campaigns have been met with success, such as in the case of the West Indian Manatee, which was recently declared no longer endangered. In aquatic environments, it can be very difficult to tell what the actual number of individuals in a species or population is, simply because the ocean is large, and humans cannot be underwater for long periods of time. This can sometimes lead to cases where species are declared extinct when there are still populations left, albeit small ones. A situation such as this was recently uncovered in the case of the Galapagos shark, a species that inhabits the coastal waters surrounding islands at mid-latitudes across the globe.

In 1993, in the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago, a chain of islets situated between Brazil and the West African Coast, the Galapagos shark was declared locally extinct. This meant that though the species might exist in other areas around the globe, it was gone from the waters off these islets. However, around 2009 and 2010, there were reports of fisherman catching these sharks, indicating some small groups of individuals might still be swimming in this area. This prompted researchers to investigate.

Fin fact-finding

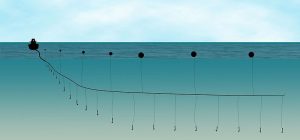

Starting in October 2010, researchers from the Universidade Federal de Pernambuco in Brazil visited the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago and put out longlines in the surrounding waters. As sharks would get caught on the longline hooks, the researchers would identify the shark species, tag them, and release them back into the water. This was done for nine years, ending in August 2019. In 2012, only a couple of years into the study, a ban on catching sharks of any kind was put in place around the islets, protecting any remaining Galapagos sharks from being caught and killed. In 2018, marine protected areas were created, which protected all ocean life in the area from being overexploited by humans. These protective measures allowed researchers to not only determine if the Galapagos sharks were no longer locally extinct, but to see the effect that different conservation efforts could have on whatever small population may have remained.

Over the course of the nine-year experiment, 195 sharks were caught. Of those, 36 were Galapagos sharks, providing concrete evidence that this species was not locally extinct around these islets. After the fishing ban on sharks was put in place, the number of sharks caught rose sharply. Once the marine protected areas were created in 2018, the number of sharks caught skyrocketed, with Galapagos sharks being caught by researchers almost 5x more often than they were in 2012. Local fishermen that were asked about the number of sharks present in the area even noted that more sharks were being spotted as the years went on.

Protecting threatened species

The study demonstrates a few points. The first is that Galapagos sharks were likely never truly extinct in the Saint Peter and Saint Paul Archipelago. Several groups of sharks were probably there all along, and simply went undetected by humans from the late 1990s to the early 2000s. Secondly, the story of the Galapagos shark in this area shows how successful conservation efforts can be. While the population of these sharks near the archipelago is likely not astronomical, it is likely in far better shape than it was a decade ago. If fishing bans and marine protected areas can work in this region, then they can likely work in other areas to conserve more critically endangered species. Thirdly, stories such as that of the Galapagos shark make it clear that just because humans cannot see a certain animal does not mean it is not out there. There are many stories about so-called “extinct” species suddenly reappearing, from tortoises to birds to mammals. By protecting populations of animals when their numbers are very low through concrete conservation measures, we can ensure that they are not lost forever.

I received my PhD in Biology from Wake Forest University, and I received a BS in Biology from Cornell University. My research focuses on the terrestrial locomotion of fishes. I am particularly interested in how different fishes move differently on land, and how one fish may move differently in different environments. While I tend to study small amphibious fishes, I’ve had a lifelong fascination with all ocean animals, and sharks in particular. When not doing science, I enjoy running, attempting to bake and cook, and reading.